And one of the prime movers of the new direction was Teddy Roosevelt, who as president helped push the American military to adopt what was essentially a bootleg copy of the gun that had done so much damage to his forces on Kettle Hill.

For more than sixty years, America had been cursed by bad decisions coming out of one office in Washington, D.C.: the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps. The head shed there controlled the nation’s weapons arsenals, including the biggest ones at Springfield, Massachusetts, and Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

The men in charge were the bureaucrats and generals who were supposed to equip our fighting men with the latest firearms and the top technology. Instead, as we’ve seen, they managed to do their best to condemn American soldiers to failure and death. They pissed away opportunities to get superior weapons and consistently chose clunkers, again and again.

When George Washington ordered his artillery chief Henry Knox to start an American weapons arsenal in Springfield in 1776, he helped spark the stirrings of the American Industrial Revolution. But by the Civil War, the arsenal was stuck in the past. The arteries were so clogged it affected the Army’s brain. Bad weapons mandated bad tactics; bad tactics encouraged bad training; bad training justified bad weapons.

“The armory also spawned a culture of obdurate bureaucracy that has afflicted parts of the U.S. military establishment down to the present day,” wrote John Lehman, who served as secretary of the Navy during the Reagan administration. “Having made a vital contribution to winning independence, the Springfield armory had great prestige in the new republic. Unfortunately, the armory and the Ordnance Corps developed an autonomy within the new War Department that rapidly hardened into orthodoxy and an aversion to new weapons technology.”

After the Revolution, the ordnance bureaucrats ignored the obvious promise of the breech-loading rifle and percussion cap and forced the military to cling to outdated muzzleloaders and flintlocks into the Mexican War era and beyond. During the Civil War, breechloaders, repeaters, and Gatling Guns were available for mass production and might have won the war for the Union much more quickly, but officials stubbornly sidetracked each breakthrough.

In the Indian Wars, they kept Winchester repeaters out of our troops’ hands. Incredibly, after the Little Bighorn disaster, Army Chief of Ordnance Stephen Vincent Benét insisted that the totally obsolete single-shot Trapdoor Springfield would remain in service as the regulation infantry shoulder weapon from 1874 to 1891. His successor, Daniel Webster Flagler, chose the Krag-Jorgensen to replace the Springfield Trapdoor over the Mauser. Why? Partly because the boob-ureaucracy thought the Krag would use less ammunition and so reduce costs. These guys had a fatal fetish for conserving ammo. I’m all for cutting back on government waste, but there’s a point where saving money ends up costing a heck of a lot more in people’s lives. The Ordnance officers flew past that point time and again.

Privately, many U.S. Army officials were horrified by the carnage wreaked by the superior firepower of the Mauser rifles at the Battle of San Juan Heights. They were determined to get their soldiers a much better gun than the Krag. Captured Spanish Mausers were carefully analyzed, and gradually an idea began to spread:

“Why not just copy the Mauser?”

And so they did.

Developed from earlier Mauser designs, the Mauser M93 used on Cuba stands at the head of a family of weapons that saw rapid improvement in the years around the turn of the century. As you’d expect, the rifle’s development and innovations in ammunition went hand in hand. Advances in the science of alloys led to stronger steel and more powerful and lighter weapons. That meant that other improvements in powder could be put to work. Cartridges could be more powerful without damaging the weapon. Bullets could go faster and farther.

The Mausers used what is known as “bolt action” to handle the complicated business of putting the ammo in place and then sending it on its way. The breech of a bolt-action rifle is opened by a handle at the side of weapon. When that handle is drawn back, the spent cartridge is ejected. The handle is then pushed forward, stripping the cartridge from the magazine and placing it into the chamber. The bolt is locked in position, and the gun is ready to fire. It’s tough to improve on this system—most of my sniper rifles were bolt-action.

Going from black to smokeless powder didn’t just make it easier to see on the battlefield. Rifle bullets could now move faster and go farther with the same or even less volume of powder. The design of the bullets and their cartridge evolved hand in glove with the powder and the rifles, becoming more efficient and cleaner in the gun.

Not to mention deadlier.

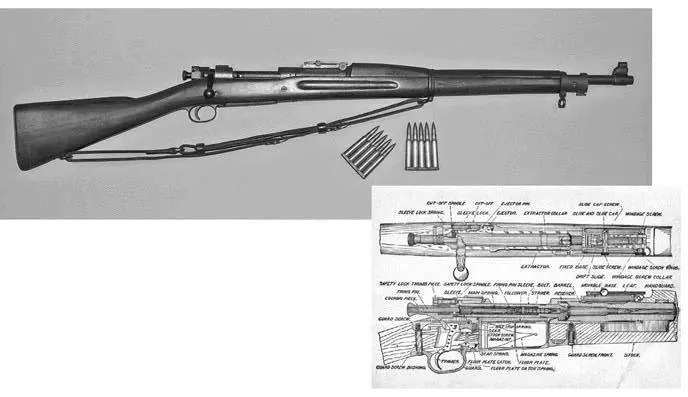

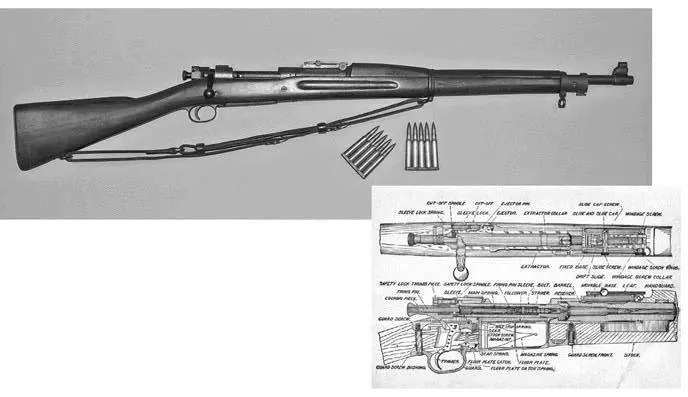

Four years after the charges at San Juan Hill, following extensive testing, experimentation, and input from veterans including Roosevelt, the Springfield Armory unveiled the five-round-magazine, stripper-clip-fed, bolt-action M1903 Springfield. Officially called the “U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, Model of 1903,” it was known by troops as the “aught three,” or, in later years, simply “the Springfield.” There were a few key differences and improvements, most notably in the firing pin, but the aught-three was pretty much a Mauser. In fact, the Americans plagiarized so badly that the U.S. government lost a lawsuit brought by Mauser and was forced to pay the foreign company hundreds of thousands of dollars in royalties. Still, the United States had its gun.

Teddy loved the new Springfield 1903 so much he put in an order for his own custom-made hunting model. For the next twelve years he used the rifle to bag more than three hundred animals on three continents, including lions, hyenas, rhinoceros, giraffes, zebras, gazelles, warthogs, hippopotamuses, monkeys, jaguars, giant anteaters, black bears, crocodiles, and pythons.

But there was one thing Roosevelt hated about the rifle’s original design. He thought the weapon’s slim, rod-type bayonet was a piece of junk. He wanted it changed, so he halted production.

The M1903 Springfield. It so closely “borrowed” from the Mauser design that the U.S. government was forced to pay royalties to the German company.

Wikipedia

“I must say,” he fumed in a memo to Secretary of War William Howard Taft, “I think that ramrod bayonet about as poor an invention as I ever saw.” The point of the slim bayonet was to serve as an emergency ramrod in case the rifle jammed. Roosevelt as well as countless Army men realized it was too fragile to do its main job. So in 1905 a sixteen-inch knife-style blade bayonet was added. The bayonet was a real beast; the devil himself wouldn’t have wanted to pick his teeth with it.

Even better was the improved ammo, which was introduced in 1906. The new cartridge was based on the old one, but had a lighter, 150-grain pointed “boat tail” bullet at its head. It became the classic American military round for decades, and remains probably the most popular civilian hunting round today. Known as the .30-06, the “aught-six” refers to the year it was introduced rather than the size of the ammo. The new ammunition made the 1903 Springfield rifle a superstar, conferring the advantages of greater speed, force, and accuracy than a round-tipped projectile. Along with the new ammo the barrel was shortened, making it a bit easier to handle.

You may have noticed that the size of rifle bullets has started coming down. Throughout history, there was a tradeoff between speed and size, weight of the gun, and ease of use. It’s tough to make a blanket statement about what ammo or bullet is better without viewing the entire system or the job that needs to get done. The rifles the Americans had in Cuba fired bigger bullets than the Spaniards; obviously that wasn’t an advantage there. But here’s an interesting observation from that war, made by Roosevelt himself:

Читать дальше