The remains of the German force retreated into the thick cover of Belleau Wood. A delighted French pilot swooped low over the scene and signaled “Bravo!” to the Marines.

A savage back and forth bloodbath followed over the next three weeks, as the two sides fought for control of Belleau Wood. The terrain was straight out of a nightmare, a barely-penetrable two-hundred-acre tangle of thick vegetation stocked with German mustard-gas mortars and machine-gun nests. In the words of one Marine commander, it was “like entering a dark room filled with assassins.” Plagued by confusing orders and bad maps, scanty food, little intelligence, and poor communications, the American Marines and soldiers launched five failed attempts to sweep the forest, coming up short each time.

On June 6, at 5 p.m., clutching his bayonet-tipped M1903 rifle, Sergeant Major Dan Daly rose from the wheat and yelled to his marines the order to advance on the German machine-gun positions bracketing the edge of the forest.

“Come on, you sons of bitches!” yelled Daly, who at a five-foot-six weighed all of 132 pounds. “Do you want to live forever?”

The only thing small about the sergeant was height. He’d already received two Medals of Honor for conspicuous bravery under fire, one in Haiti and the other in China. A thousand Marines stood up and ran forward when he yelled. The Germans unleashed a fierce barrage of rifle, machine gun, and artillery fire. “The losses were terrific,” said Colonel Catlin. “Men fell on every hand there in the open, leaving great gaps in the line. [3rd Battalion commander Major Ben] Berry was wounded in the arm, but pressed on with the blood running down his sleeve. Into a veritable hell of hissing bullets, into that death-dealing torrent, with heads bent as though facing a March gale, the shattered lines of Marines pushed on. The headed wheat bowed and waved in that metal cloud-burst like meadow grass in a summer breeze.”

When they reached the trees, Private W. H. Smith and his squad put their Springfield 1903 rifles to good use against lingering German troops: “There were about sixty of us who got ahead of the rest of the company. We just couldn’t stop despite the orders of our leaders. We reached the edge of the small wooded area and there encountered some of the Hun [German] infantry. Then it became a matter of shooting at mere human targets. We fixed our rifle sights at 300 yards and aiming through the peep kept picking off the Germans. And a man went down at nearly every shot.”

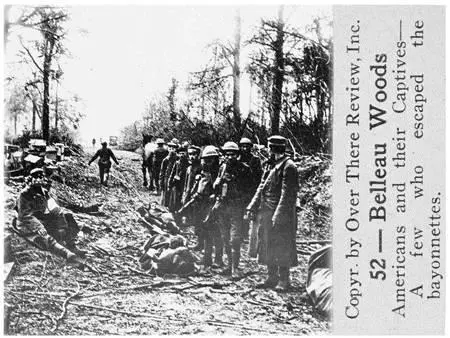

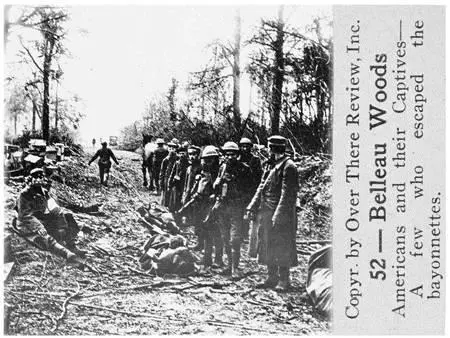

German officers and soldiers were stunned at both the tactics and the appearance of the attacking Americans. The Marines used “knives, revolvers, rifle butts and bayonets,” complained one German. “All were big fellows, powerful, rowdies.” The Marines were so fierce, the Germans were convinced they were drunk and oblivious to pain. My guess is that they were just being badass Marines. Or as a German military report put it, “vigorous, self-confident, and remarkable marksmen.”

A letter was found on the battlefield in which a German soldier despaired, “They kill everything that moves.”

Yes to that. And they still do.

Captain John W. Thomason wrote that the Marines’ rifles let them carry the day. “All [the German] batteries were in action, and always his machine-guns scourged the place, but he could not make head against the rifles. Guns he could understand; he knew all about bombs and auto-rifles and machine-guns and trench-mortars, but aimed, sustained rifle-fire, that comes from nowhere in particular and picks off men—it brought the war home to the individual and demoralized him. And trained Americans fight best with rifles. Men get tired of carrying grenades and chaut-chaut [French-made machine gun] clips; the guns cannot, even under most favorable conditions, keep pace with the advancing infantry. Machine-gun crews have a way of getting killed at the start; trench-mortars and one-pounders are not always possible. But the rifle and bayonet goes anywhere a man can go, and the rifle and the bayonet win battles.”

By midday, the Marines had settled things. They owned the woods. The Germans weren’t getting to Paris, except maybe as tourists after the war.

It was the bloodiest day in U.S. Marine Corps history to that point, with 1,087 casualties, more than the Marines had suffered in the Corps’ whole previous history. But they died heroes and helped save the war. It would be nearly three weeks before the sector was completely secured, but the last great German offensive of the war was pretty much history.

“The effect [of the Marine action at Belleau Wood] on the French has been many times out of all proportion to the size of our brigade or the front on which it has operated,” American General James Harbord wrote in his war diary. “They say a Marine can’t venture down the boulevards of Paris without risk of being kissed by some casual passerby or some boulevardiere. Frenchmen say that the stand of the Marine Brigade in its far-reaching effects marks one of the great crises of history, and there is no doubt they feel it.” Years later, the commander of the 1st Infantry Division, General Robert Lee Bullard, concluded that the Marines “didn’t ‘win the war’ here, but they saved the Allies from defeat. Had they arrived a few hours later I think that would have been the beginning of the end.”

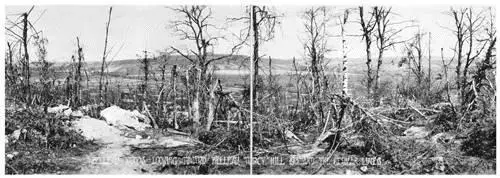

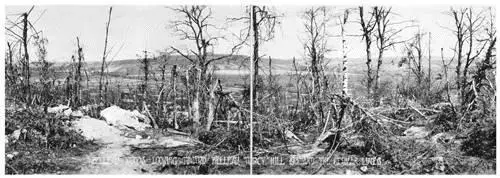

The site of the Marines’ greatest victory during World War I.

Library of Congress

“American cemetery—Belleau Woods, France. Where over 2,000 regulars and Marines who gave their lives … sleep their last sleep.”

Library of Congress

The grateful French renamed the forest “Bois de la Brigade de Marine,” or “Wood of the Marine Brigade,” and awarded the 4th Marine brigade the Croix de Guerre.

The Springfield 1903 remained in service through World War II and was even used in Korea and Vietnam. At least one World War II general is known to have carried and used his with great relish. Omar Bradley, at the time an Army corps commander, habitually kept his in his Jeep in Africa and on Sicily. General Bradley often used the gun to take potshots at attacking German planes.

Though an excellent shot, Bradley is not known to have brought down a plane.

Then again, the German pilots missed him as well.

Much of the Springfield’s service in World War II was as a sniper weapon. Army sergeant William E. Jones used it in Normandy with great success. So did many others. While not initially designed as a sniper weapon, its inherent abilities of sure fire and long range made it a good one. Jones credited much of his success to his scope, which provided 2–5× magnification. It was a huge advantage over iron sights, even though it’s a far cry from even the less expensive civilian hunting sights we use today.

Inevitably, improvements in technology made the Springfield obsolete as a sniping weapon. Still, its influence lived on, as did its ammunition. Legendary Vietnam-era sniper Carlos Hathcock—the greatest American combat sniper ever—shot a .30–06 from his Winchester Model 70. Even today, the longer range weapons preferred by most snipers can trace their roots back in some way to the bolt-action long gun and its ammo.

Читать дальше