Sergeant York lives on in American mythology as one of the toughest soldiers who ever lived. The “Government Model” 1911 pistol he used to pop those Germans has a place right next to him too. The M1911 is a true warrior’s tool. It figures into quite a number of war stories, and for its time and place was probably the greatest handgun ever made. We’re a hundred years from its birth, but it’s still going strong. It’s the basis for any number of customized models, including a SEAL commemorative by Para-Ordnance that’s one of several M1911s in my personal collection. Even when gun makers don’t use it as their model, it’s the design they’re looking to beat.

Many gun experts agree it rules the roost. When American Rifleman recently named their top ten guns of all time, they practically gushed over the weapon. “It fits the hand like a trusted tool,” wrote Brian Sheetz. “It functions without fail. It has proved itself in brutal service throughout two world wars. It works just as well on the firing line and on the front lines of combat today as it did the day it was adopted.” Editor Wiley Clapp added, “I cannot name a handgun that delivers more mud-and-sand reliability than the Government Model.”

The gun’s roots go straight back to the last days of the nineteenth century. The U.S. Army was deep in the jungles of the Philippine Islands, which they inherited after the Spanish-American War. Our soldiers were fighting a fierce counterinsurgency war against radical Islamist Moro tribesmen. The tribesmen had a habit of charging Americans with long knives while wearing wood-and-leather body armor. The Moro fanatics supposedly fought under the influence of powerful narcotics, which made them almost immune to pain. Shoot them, and they just kept coming. It was like something out of a zombie movie. The regulation firearms at the time, .38 Long Colt revolvers and .30 Krag rifles, didn’t have the man-stopping power for this kind of an attack.

Humbled by the experience, the Army soon conducted experiments on some unfortunate live animals and human cadavers, and decided that American soldiers needed a larger caliber weapon on the hip. What they wanted was something that would stop a horse.

Literally.

Philippines, 1899: “Kansas volunteers firing from trench.”

Library of Congress

“The cavalry doctrine of those days was if you could drop a horse in its tracks, you got rid of the rider as well,” explained military historian Edward Ezell of the Smithsonian Institution. It was two for the price of one. So the military went looking for a handgun that could do the job. A historic “bake-off” was held by the Army. Weapons from five companies were put to the test. After years of trials, the championship match was conducted on March 3, 1911, when two finalist handguns faced off against each other in a competition somewhere between Survivor and American Idol, Pistol Edition.

At the end of the tests, one gun stood supreme: a semiautomatic, locked-breech, single-action Colt pistol. The handgun chambered .45-caliber, 230-grain, full metal jacket, smokeless rounds fed from a single stack, seven-shot magazine. The winning prototype had fired no less than six thousand rounds. It had been dunked in acid and salt water, and forced to handle deformed and misloaded rounds. The board of judges found that “the Colt is superior, because it is more reliable, more enduring, more easily disassembled when there are broken parts to be replaced, [and] more accurate.”

In other words, it rocked.

The winning design was the brainchild of the Leonardo da Vinci of firearms design: John Moses Browning. The world of guns would be very different without Browning, and the M1911 was his baby. It became the official sidearm of the U.S. Army on March 29, 1911. The U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps followed suit, adopting it in 1913.

When it was adopted, Browning’s Colt was officially known as the “Colt Caliber .45 Automatic Pistol.” The words “United States” were added to the title, along with the designation M1911 and then M1911A1 for the improved version that came out in 1924. The word “automatic” has remained, in one of the most common nicknames, the .45 Automatic. It’s also in the name of the cartridge it takes, .45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol). The way we classify guns these days, though, the weapon is a semiautomatic; you have to pull the trigger for each bullet to fire.

It is no exaggeration to give John Browning credit for creating much of the modern world of guns. “To say he was the Edison of the modern firearms industry does not quite cover the case, for he was even greater than that,” wrote Captain Paul Curtis in Guns and Gunning. “Browning was unique. He stood alone, and there was in his time or before no one whose genius along those lines could remotely compare with his.”

Browning came up with many of the big breakthroughs of the last century and a half in “a creative rampage unmatched in the history of firearms development,” wrote authors Curtis Gentry and John Browning (the inventor’s son) in their book, John M. Browning: American Gunmaker . “His speed and productivity made his accomplishments blur.”

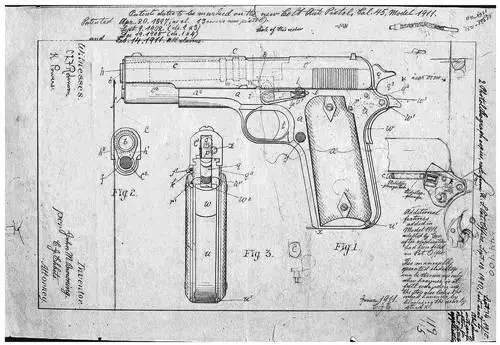

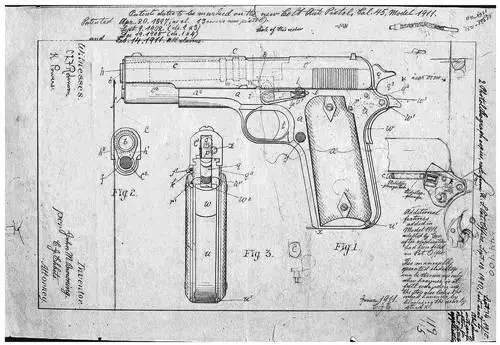

Above: John Browning’s designs for his “Auto Pistol, Cal .45, Model 1911,” submitted to the U.S. Patent Office in September 1910. Below: the finished product.

U.S. Patent Office (top); American Rifleman (bottom)

Born in 1855 to a Mormon gunsmith in Ogden, Utah, John Moses Browning quit school before seventh grade to work in his family’s shop. He earned a hands-on education in firearms manufacturing and engineering from his dad, who’d developed a prototype “slide-action” repeating rifle. The younger Browning’s inventive mind quickly showed itself: He created his first gun as a boy and earned a U.S. patent before he was twenty-five.

In 1883, a salesman for the Winchester Repeating Arms Company traveled through dusty Ogden and, by chance, tested Browning’s newly patented rifle. The gun made its way to T.G. Bennet, the vice president and general manager of Winchester (Oliver Winchester had died in 1880), who was so impressed that he traveled to Ogden and personally bought Browning’s design for eight thousand dollars. The purchase began a two-decade relationship between the designer and the Connecticut manufacturing giant.

Browning’s inventions were captured in 128 patents covering eighty weapons, including the classic Winchester Models 1886, 1892, and 1895 lever-action rifles; the Model 1894, and the 1893 and 1897 Winchester pump-action shotguns. After a break with Winchester, he produced a revolutionary series of semiautomatics and machine guns. Among them: the Browning Auto-5 Shotgun (produced under license as the Remington Model 11), the legendary Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), the .50-caliber M2 Browning machine gun, and the M1911 pistol and its descendant, the 9mm Browning Hi Power. He also designed the .45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) cartridge fired by the M1911.

Browning didn’t use blueprints. According to his descendant Bruce W. Browning, he would dream up a weapon in his head, work out a bunch of problems and kinks, then build a prototype based on his ideas. Only when he had the model working would he turn it over to others to be drawn and “engineered.”

Читать дальше