Just a show?

Capone heard a car speed off. He got to his feet and started for the door to show he wasn’t a pussy.

Frankie Rio flew through the air, tackling his employer and shoving his face to the floor.

“It’s a stall, boss,” grunted Rio. “The real stuff hasn’t started. You stay down.”

Moments later, nine sleek limousines and touring cars slid up in front of the hotel. The barrels of Thompson submachine guns poked through the windows and opened fire. More than a thousand bullets poured into the building. The gunmen were acting on orders of Capone’s rivals, and they didn’t stop until they ran out of ammunition.

As the others paused, a man wearing a khaki shirt and overalls got out of the next to last car. He kneeled down on the sidewalk in front of the hotel, and began spraying neat rows of gunfire across the interior and exterior of the building. Drum mag empty, he reloaded and fired some more. Then he got up and went back to his car. Slow and easy, like nothing had happened.

Three blasts on the horn and the limos burned rubber.

Not one of the bullets fired in Al Capone’s direction hit him. Several other people were wounded, including a five-year-old boy and his mother who’d been outside in their car. Capone paid their medical and other bills, which totaled ten thousand dollars. It was a business expense.

The shooting spree would go down in history as the Siege of Cicero. Its target was overlord of the “Chicago Outfit,” a one-hundred-million-dollar-a-year crime empire based on the three pillars of American vice: gambling, prostitution, and booze. “I am just a businessman, giving the people what they want,” Al Capone once explained. “All I do is satisfy a public demand.”

That was booze, mostly. Prohibition had become law the passage of the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act in 1919. From then on, practically every drink a man or woman had put money in the pocket of a criminal somewhere.

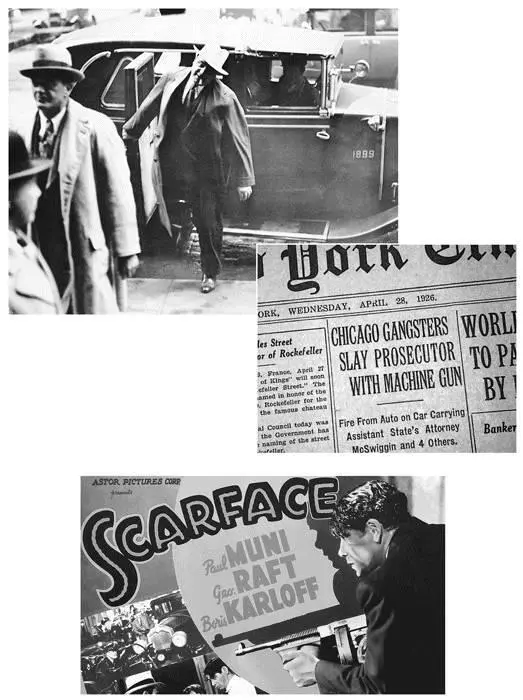

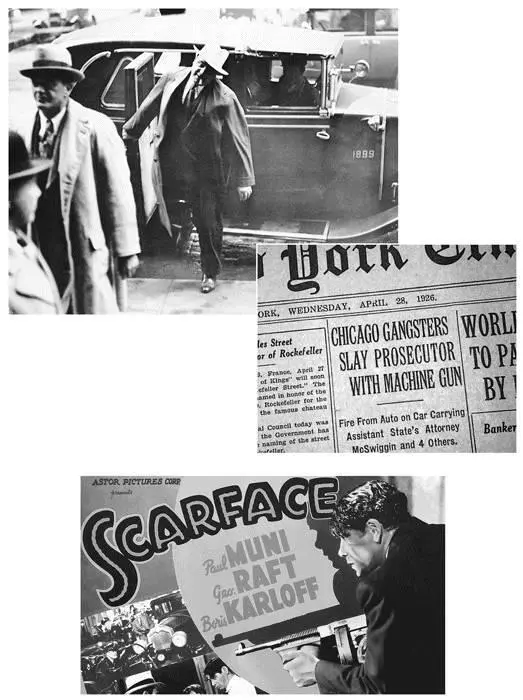

Al Capone—nicknamed “Scarface”—made national headlines and inspired numerous films, such as this 1932 Howard Hughes production.

United Artists Corporation (bottom)

Three weeks after his lunch was interrupted at the hotel, Capone got his revenge. Rival gangster Hymie Weiss, who Capone fingered for the attack, was gunned dead in downtown Chicago. The instrument of his execution: a Thompson submachine gun.

The Thompson went by many names. “Tommy Gun” is the one most of us know. It was called that pretty much from the beginning. But the Chopper, Trench Broom, Chicago Typewriter, and the Annihilator have all been popular at one time or another.

The gun has a reputation as being hard to handle. That’s a case of the bark being worse than the bite, at least if you’re prepared and know what you’re doing. The drum mag gives it more balance than you’re led to expect by the stories. The kick is there, sure, but it’s no more serious than most other full autos. Hold on the trigger and the gun begins to climb, but again, that’s pretty much what you’d expect. Most of the Tommy men, which is what they called the mobsters who made it famous, fired only in small bursts. That gave them a lot more control than you see in the movies. Lay on the trigger a bit and the flash is very noticeable in the dark, but it’s really the sound you remember. The old ’30s movies don’t get it exactly right, but they are darn close.

Invented to help clear trenches in World War I, the gun came too late to be used there. Then the gangsters got a hold of it. So did the movies. Capone and his cronies—real and in the talkies—used the rapid-fire weapon so well and so often most of us still consider it a gangster gun. But in fact, the Thompson was a favorite among GIs in World War II, when something like a million and half were made. The gun and its bootleg clones even saw action in Korea and Vietnam.

And why not? It certainly looks cool, especially with the drum magazine. And while not exactly known for accuracy, there’s no arguing with the results. The Tommy gun was far and away the most lethal handheld automatic weapon you could get in the first half of the twentieth century, and it’s still no slouch.

The idea of a rapid-fire battle weapon had been around for centuries, but no one figured out how to make one work until the 1800s.

One of the first prototypes of a fast-firing, multiple-round field weapon was the “Union Repeating Gun.” Nicknamed the “Coffee Mill Gun” by Abraham Lincoln after he viewed a sales demo in 1861, the hand-cranked contraption fired .58-caliber paper cartridges fed into a breech by a hopper. Lincoln, as he often did, spotted its potential.

“I saw this gun myself, and witnessed some experiments with it, and I really think it worth the attention of the Government,” he told his Ordnance Department.

As usual, the department’s chief—dinosaur and enemy of innovation General James Ripley—stalled. A handful were eventually ordered for the Union army’s use, but they saw no use in battle. The Coffee Mill gun had a number of problems, most especially a nasty habit of overheating. So your guess is as good as mine about whether it might have helped the Yanks much.

The Gatling gun was a different story. The multi-barrel, hand-cranked weapon was patented in 1861 by North Carolina–born doctor Richard Jordan Gatling. Richard was a serious inventor and tinkerer. After settling in the Midwest in his thirties, he developed a revolutionary seed planter and a steam plow. When the Civil War started, his imagination turned to weapons. He aimed big, hoping to produce a gun that would do the work of many men.

He definitely got that part right. It took him a few versions and models over the years to perfect his vision and keep the Gatling bullet cannon at the cutting edge of the available technology. But for roughly twenty-five years it was the state of the art.

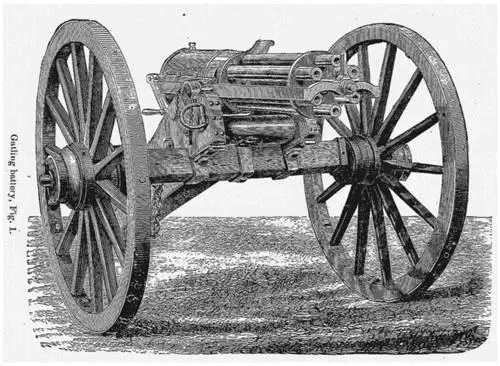

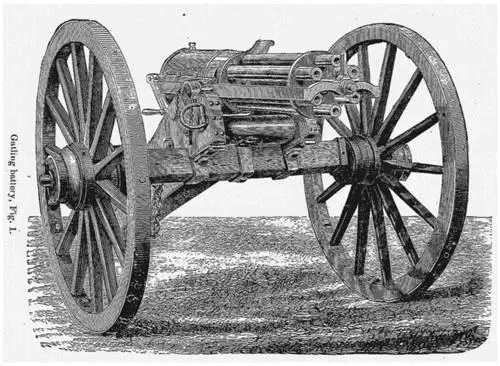

A six-barreled Gatling gun.

Library of Congress

What it wasn’t, technically speaking, was what we now think of as a machine gun. Because unlike every machine gun today, the Gatling required someone to turn the handle to make it work. It was kind of like an organ grinder, only the music you’d be making had a deadly downbeat.

Gatling guns played an insignificant role in the Civil War, and they didn’t change the course of any battle. Maybe their most dramatic appearance was off the battlefield, when the weapons were mounted on the roof of the New York Times building in Times Square on July 17, 1863.

The good citizens of New York weren’t too keen on being drafted to fight for the Union. They were especially angry at the latest provisions of the law, which allowed the rich to buy their way out of service. Mobs rampaged through the city streets. The Times was a vocal supporter of Lincoln and the Republicans, and the crowd decided that it had exercised its First Amendment rights a little too vigorously.

Journalists were different in those days. A Times editor passed out rifles to his staff, set up two Gatlings borrowed from the Army in the windows for all to see, and placed another one right on top of the building.

He took the trigger himself.

“Give them grape,” he yelled loud enough to be heard over the approaching horde. “And plenty of it.”

“Grape” was a type of shot or bullet fired from cannons, but the expression was basically slang for “cleared hot to fire.” In modern English, his words meant, Shoot the bastards, and do it a lot.

Читать дальше