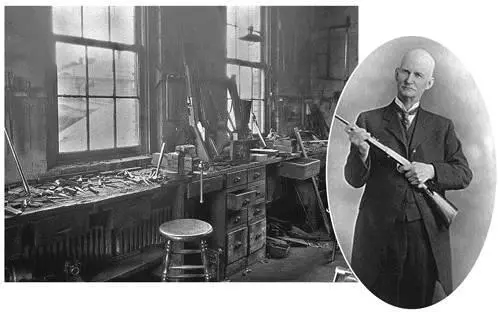

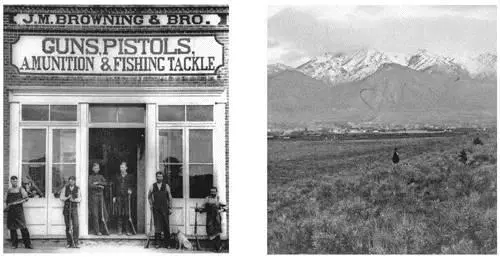

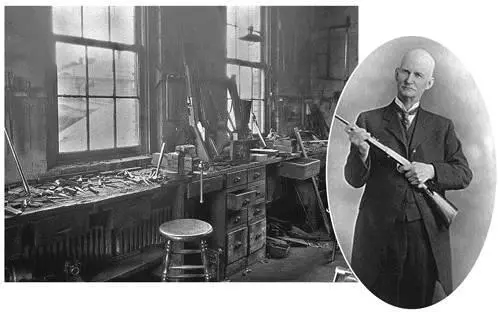

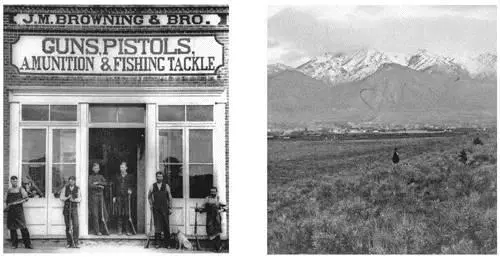

Above: Where the magic happened: John Moses Browning’s work bench. Below left: Browning’s Ogden, Utah, storefront. Below right: Ogden, 1874, still very much the Old West.

Browning Arms Company (top right and bottom left); Library of Congress (top left and bottom right)

This American genius was working for Colt when he designed the M1911. He had developed an earlier Colt pistol, the Colt Model 1900. Inspecting the weapon, you can see some of the ideas that would make the 1911 a classic. The older gun was a self-loaded weapon that fired a .38 ACP round. It looked something like a smaller M1911 with a longish barrel.

Inspect a Browning design—any Browning design—and you can see the influence of the American frontier. Survival in the West depended on keeping things simple, and making them tough. The simpler and more rugged, the better. It is the winning formula for a gun, or for any tool really.

“Make it strong enough—then double it,” Browning said. “Anything that can happen with a gun, probably will happen, sooner or later.”

Like the Model 1900 before it, the Model 1911 uses a small amount of the energy from the cartridge as it is fired to eject the spent shell and cycle a new round into place. The energy that causes the gun to recoil is used in the M1911 to slap out the old cartridge and put a new one in its place.

The idea of “self-loading” (or semiautomatic) is now common, but it was new at the turn of the century. That alone would have spooked the Army brass in years gone by, but the fresh faces at the top were no longer afraid of cutting-edge design… as long as it worked.

And the M1911 did.

To the shooter, the gun’s brilliance starts with loading, where a spring-loaded magazine is easily filled with bullets. The mag slips vertically inside the pistol grip. Rack the pistol—pull back the slide (the top of the gun, sitting over the barrel). This chambers a round. Aim. Fire.

The recoil energy of the bullet pitches the slide back. The spent shell pops out quicker than you can see it. A new one pushes up from the magazine inside. Aim, and fire again. Nothing to it.

It’s not just the action or its internals that make the gun so sweet. The trigger is short and comfortable. The pistol weighs just 2.4 pounds before you pop in the magazine. The recoil is manageable, so you can shoot with one hand reasonably well. The gun has both grip and manual safeties, so it’s hard to fire accidentally.

Browning’s design was simple enough that it could be mass-produced with good, steady results, unlike its main competitor from the era, the more complex German Luger. Fewer parts also meant less could go wrong in miserable combat conditions. Part of the reason it’s tough as hell.

A Springfield TRP Operator 1911 took a frag for me in Fallujah back in 2004. My gun had a bull barrel, and I modified it with custom grips and a rail system. I doubt Browning would have recognized it at first glance. Still, at its very heart it was a M1911. The toughness he’d baked into the cake back a hundred years ago saved my hide. So I owe the man my gratitude—I might not have been able to walk after that if it weren’t for him.

By the way, the very same .45 that went through those original torture tests in 1911 is still with us, looking none the worse for all that wear. It and a nearly identical hammerless prototype variation are housed at the John M. Browning Firearms Museum in Ogden, Utah.

The M1911 first saw combat in 1916 when General Pershing drove into Mexico in a fruitless search for rebel leader Pancho Villa, whose troops had looted and burned the town of Columbus, New Mexico.

In World War I, the sidearm was used by many American troops in close-quarter battles in the trenches, forests, and fields of Western Europe. “The bottom line was that when Americans shot Germans with Colt .45 automatics, the Germans tended to fall down and die,” wrote historian Massad Ayoob. “When Germans shot Americans with their 9mm Luger pistols, the Americans tended to become indignant and kill the German who shot them, and then walk to an aid station to either die a lingering death or recover completely. Thus was born the reputation of the .45 automatic as a ‘legendary man-stopper,’ and the long-standing American conviction that the 9mm automatic was an impotent wimp thing that would make your wife a widow if you trusted your life to it.”

The M1911 gained more hard-core battle experience in the hands of Marines and bluejacket sailors fighting in Latin America and the Caribbean during the “Banana Wars.” In Haiti in 1919, guided by a turncoat Haitian general, a Marine sergeant named Herman Hanneken used a disguise to sneak into the lair of rebel chieftain Charlemagne Péralte. Hanneken gunned him down with a M1911 Colt .45 in front of hundreds of Péralte’s followers. In the chaotic gunfight that followed, the tough Marine somehow managed to escape with his life. He was later awarded the Medal of Honor.

A few months later, a team of Marines snuck through the Haitian jungle to the headquarters of Benoît Batraville. Batraville had taken over after Charlemagne Péralte’s death. The Marines were out for some payback for their fallen comrade Lieutenant Lawrence Muth, who had been killed and cannibalized by Batraville’s gang. (The bandits cut out the Marine’s heart and smeared his blood on their rifles to improve their marksmanship.)

Gunnery Sergeant Albert A. Taubert approached the entrance of the bandit’s cave, clutching an M1911. Taubert, a highly decorated World War I veteran, spotted Batraville. As the Haitian opened fire with a .38 revolver, the Marine calmly shot and killed him. The 1919–20 Second Caco War ended soon afterwards.

In World War II, the M1911 was the regulation sidearm for most Americans fighting in Europe and the Pacific. To meet the needs of war, the government contracted with numerous manufacturers—including some unusual folks like the Union Switch & Signal railroad company and the Singer sewing machine corporation—to produce almost two million pistols.

The gun became famous for keeping our guys alive in the hairiest situations. In 1942 on Guadalcanal—America’s first offensive against Japan—Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone is said to have gone through the jungle armed only with a Colt M1911 as he fetched ammo for his machine gun unit in the middle of a Japanese attack. Pounded by the enemy, Basilone and his section were down to two machine guns and three men, one of whom had lost his hand. Basilone and his Marines held off screaming “banzai” charges by Japanese troops all night, waiting for reinforcements to arrive. Their stand helped the Marines hold Henderson Field, a key airbase in the campaign. The sergeant received the Medal of Honor for his bravery; he later died in action on Iwo Jima. Basilone was one of only two Marines to receive both the Medal of Honor and the Navy Cross during the war.

On the other side of the war, American paratroopers found the weapon came in handy in the predawn assault behind the beaches on D-Day. In the cloudy and windy darkness, 2nd platoon, F Company of the 82nd Airborne’s 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment began jumping from a C-47 aircraft. In the dark, windy night, the troopers descended over a wider area than planned. Several fell directly into the French town of Ste.-Mère-Église, one of their primary objectives, instead of outside the town.

World War II poster featuring the G.I.’s favorite sidearm, the M1911.

Library of Congress

Two, in fact, landed on the old Roman Catholic church at the center of town. Private Ken Russell slammed onto the church roof. Private John Steele’s chute got tangled on the bell tower. A third paratrooper, Sergeant John Ray of Gretna, Louisiana, hit the ground on the church square nearby.

Читать дальше