“University arrange this nice place for me. I take down all the Klimt posters. At Harvard, you could tell if a girl would sleep with you by her poster. Modigliani— sì . Klimt— no . I want to set the right mood.”

“Well done. But the outfit? Why are you dressed to go stag hunting with an archduke?”

“It is part of my very clever plan.” Alessandro produced a garment bag from the hall closet and waved it with a flourish. “There is a ball tonight, and the scientist you wish to meet, Frau Doktor Müller, she will be there. You and me, we make friendly with her and then, boom, she say yes to enrolling Pols in the study.”

It wasn’t a bad idea. Alessandro’s charms were legendary, and no woman seemed ever to say no to him. If anyone could sway Bettina Müller, it was Alessandro, especially at a ball.

“Do I dare ask what’s in the bag?”

“This is a Tyrolean Ball. A special event being held at Rathaus. Traditional dress, this is mandatory. These Austrians are very serious about their balls.”

Sarah’s laughter was cut short when Alessandro whipped off the garment bag.

“Yeah, I’m not wearing that.” The gown was an upscale version of the dirndl, or traditional Alpine peasant dress. There were three layers to the outfit—a white scoop-neck cropped blouse with puffy elbow-length sleeves, a midnight-blue velvet dress with an embroidered bodice, and a forest-green silk taffeta apron. It came with white tights and black flat shoes. She would look, Sarah thought, like an extra from Chitty Chitty Bang Bang .

“You’ll wear it for Pols,” said Alessandro. “And I will promise not to post pictures on Facebook. Maybe.”

Sarah took the dress from him.

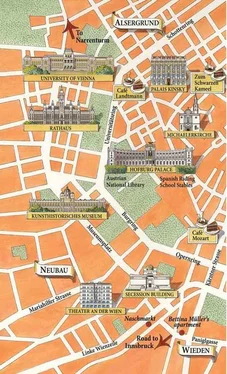

Alessandro had slightly underestimated Sarah’s dress size and slightly overestimated her shoe size, so once she was dirndled up and shuffling along, Sarah felt like a well-trussed duck. Remarkably, their costumes caused nary a second glance as they strolled through streets where every third building was a landmark of historic or cultural significance. Alessandro pointed out the Secession Building, where artists like Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, and Carl Moll had made their stand against the gemütlichkeit culture of middle-class coziness and complacency that reigned at the end of the nineteenth century in Vienna. And then Café Museum, originally designed by Adolf “ornament is crime” Loos, where the artists had gone to drink coffee, argue, and seduce beautiful women into modeling and more. They reached the Opernring and the lit-up State Opera House came into view, decorated to within an inch of its life in Neo-Renaissance splendor and topped with equestrian statues.

“This has tragic story,” said Alessandro. “When the building was completed, Emperor Franz Joseph said the building sat a little low. And so one of the poor architetti killed himself in shame, and the other died of a broken heart.”

“Never read reviews,” said Sarah, struggling to catch a deep breath in the dirndl.

“Or give them.” Alessandro nodded. “Franz Joseph felt so bad that after, whenever anyone ask of him what he thought of some building, he just said, ‘It is very nice. I like it very much.’”

They passed a blindingly pink coffee shop: Aida. Alessandro explained that Aida was a chain, but a good example of a Konditorei , a pastry shop favored by women who went to gossip and eat pastries, as opposed to the more macho Kaffeehaus , where men went to gossip and eat pastries.

“Mark Twain said that, outside of Vienna, all coffee was merely liquid poverty,” Sarah commented.

“It is true.” Alessandro sighed. “The coffee is heaven. But the food is awful. Knödel. A crime against pasta.”

* * *

Alessandro steered her toward Maria-Theresien-Platz, so Sarah could take in the enormous white and pale gray edifices arranged around the edges of a vast green square. Beyond this lay the even more massive Hofburg complex, with its monuments to the power of the Hapsburgs and the time when Vienna had been the seat of the Holy Roman Empire, powerful and seemingly indestructible. Now all of these places were simply part of Vienna’s perfectly preserved past. There was something, Sarah decided, a little smug about all this magnificence. Well, historically, Vienna had had the reputation of being a decadent, indolent city. Beethoven had once sneered in a letter that “so long as an Austrian can get his brown ale and his little sausages, he is not likely to revolt.”

Moving along, they passed the Volksgarten, the enormous Greek Revival–style Parliament building, and then turned into the approach to the Rathaus, Vienna’s imposing city hall, dressed to the nines in Gothic splendor, and boasting a statue of a knight in armor atop its lofty spire.

“Cheese and rice,” muttered Sarah (a favorite expression of her father’s) as they sailed into the majestic Festsaal . The ceremonial hall stretched the entire length of the building. She took in the barrel-vaulted ceiling, the parquet floors, the three-sided gallery, the statues and arcades, and the ornate flights of stairs. She counted sixteen chandeliers. Already there was a huge crush of people, all costumed, all wearing expressions of delight and anticipation in the frivolity to come. Members of an orchestra were settling themselves in one of the niches.

“I’m not going to have to waltz, am I?” Sarah asked, stumbling slightly in the overlarge shoes. “I don’t exactly have the moves like Ginger.”

“I will lead,” Alessandro said with a mildly sadistic smile. “Marie!” An exceptionally tall woman surrounded by a group of young ballgoers turned and then strode toward them, smiling, her wide shoulders and the stiff flounces of her many petticoats cutting a swath through the crowd. “Sarah, this is my friend Frau Professor Marie-Franz Morgendal. Marie-Franz teaches history of science at the university. She is also big Beethoven lover.”

“Frau Doktor Weston,” said Marie-Franz in careful, accented English. Her voice was deep and warm. “I read your book on Beethoven and enjoyed it very much. It was wonderfully insightful!” Sarah’s university had published her doctoral thesis on the correspondence between Beethoven and the 7th Prince Lobkowicz. Sarah had not mentioned in her book that some of her insights had come while she was on the drug Westonia, which had allowed her to actually see Beethoven and hear him play. It wasn’t the kind of thing you could tuck into a footnote.

“Please call me Sarah.” She had heard that Austrians were very big on titles, but “Dr. Weston” still sounded very strange to her.

“Yes? Then you must call me Marie-Franz. Sarah, I see that you have also tied your apron strings to signify you are an unmarried lady?” Sarah looked down at her apron, bemused. She hadn’t known she was sending a signal about her marital status.

“What is the tying that signals ‘troublemaker’?” asked Alessandro. “Sarah should have this.”

Marie let out a booming laugh as they were joined by a tiny, beautiful girl, whose pink hair and tattoos gave the whole dirndl thing a punk twist. Alessandro introduced the girl as Nina Fischer and explained that she was one of Bettina Müller’s grad students. Nina seemed fully aware of Alessandro’s plan and offered Sarah some advice.

“Play it cool, yes?” she said to Sarah. “Frau Doktor Müller is brilliant, but she can be a little . . . I don’t know if you have this word in English.” Nina switched to German, in which Sarah was fluent, and Sarah learned that Doktor Müller was “tricky.” Nina then introduced her escort, who must have been at least twenty years older than Nina and had the half-avaricious, half-desperate look of someone who knew his dates with young women were numbered, and he needed to make the most of them. “This is Heinrich von Hohenlohe,” said Nina, managing to look both proud and a little embarrassed as she pronounced the aristocratic “von.” But the name caught Sarah’s attention for a different reason. She remembered that Nico had said the von Hohenlohe family had the healer Philippine Welser’s papers and was highly possessive of them. Given the too hungry look of this guy, Sarah was glad that Nico already had the recipe he needed.

Читать дальше