This required a bit more whiskey. But he wasn’t done yet.

Nico arrived at the Science Museum an hour before closing and made his way to the fifth floor. He skirted a group of foul-mouthed schoolboys and made a brief inspection of camera locations and other security devices. Nothing a few magnets, a mirror, and a little patience couldn’t get past. He made his way to the Giustiniani medicine chest. A nice little example of sixteenth-century pharmacopoeia. One hundred twenty-six bottles and pots within the case still contained their original elements. He only needed two of them for Philippine’s recipe. Theriac and eagle bezoar.

No.

The medicine chest was gone. Not only gone, but in its place stood a small figurine of Khnumhotep, manager of ka-priests in ancient Egypt. Khnumhotep had no business being in this particular case of Renaissance medicine. His presence was an outrage, a deliberate insult.

Khnumhotep was a dwarf.

Nicolas Pertusato had an opponent. Game on.

* * *

Three hours later he was, Nico realized, not quite able to follow the lines of cobbles in the sidewalk. It might actually be that he was truly drunk now. He could not perfectly recall, for instance, what year it was.

Or what century.

Lincoln’s Inn Fields. He had been here often enough. Oh, yes. He was right near Soane’s house. Soane! Soane was excellent company. Soane would be helpful.

Nico made his way to number 13 and rang the bell.

“Soane!” he yelled up at the windows. “Soane! Open up! I want to raid your medicine chest.”

“It’s closed,” said someone behind him, striding past. Some uncouth ruffian without a hat. Where was his own hat? He seemed to be filthy. Luckily, Soane would let you in if your feet were clean.

Nico tried the door again to no avail. Soane must be upstairs, having a wee nip himself. Since his wife had died, he’d hardly gone out at all, and Nico knew he’d be grateful for a visit. Soane wasn’t comfortable at social gatherings, though his perceived deficiency wasn’t height, but class. The son of a bricklayer, he had worked his way up to being a prominent architect for all the toffiest toffs in London’s West End, but his real passion was teaching, and he had opened up his fascinating little house to visitors just a few years earlier, welcoming anyone with an interest in classical architecture and antiquities and offering them guided tours and cups of tea. Soane’s Museum and Academy of Architecture, he called it, which Nico found rather pretentious. Soane’s Future Jumble Sale, more like.

Fortunately, among his collectibles was a certain desk with a certain drawer (number 13) that contained a nice sampling of alchemical ingredients.

Nico made his way around back, where he knew a way up the drainpipe and into the second-floor window. It was on a rainy night like this that Nico had helped Soane build a funerary monument to Fanny, Soane’s wife’s dog. They had gone out in the middle of the night and found an unmarked headstone in the churchyard of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, brought it home, then Nico had inscribed it. Alas, poor Fanny! it had read.

Soane knew how to laugh.

The window was stickier than he remembered, but Nico eventually jimmied it open and made his way through the darkened house, keeping quiet so as not to wake the dogs. Soane could be a bit squiffy about lending things. He would get what he needed first, and then go wake up his friend. Nico tiptoed down the stairs to the basement, feeling his way in the dark, which wasn’t easy since Soane was perhaps the biggest of all British pack rats. He never saw a Greek or Roman cornice or chunk of masonry he didn’t want to bring home.

There it was. The desk. And there was the drawer and now . . .

No.

Removed for curatorial purposes. But this was Soane’s home. The only curator here was Soane . This was beyond a joke. Furious, Nico charged toward the staircase, tripped, and fell face-first into something very hard.

Oh, for fuck’s sake. He had fallen into Soane’s marble sarcophagus. Soane had bought it from an Egyptian dealer and it was reputed to be more valuable than anything like it in the British Museum. To celebrate its arrival Soane had thrown a party for three hundred people and made them come in and view it in shifts, with the house all lit by candles.

Nico banged his head against the side of the sarcophagus in frustration. It would do him no good. He could bash his head for hours and there would be intense pain, blood, and probably a twenty-year headache, but he wouldn’t die. And Oksana would give him hell about the bruises.

The alcohol was already wearing off. Of course Soane wasn’t here. This really was a museum now. Soane had died in 1837. Nico had attended the funeral.

So many funerals. He would stand at the graves of them all, every last one of them.

Sarah had brooded about Pols during the long train ride to Vienna, ignoring her Ohioan seatmate’s breathless, excited narration of every landmark—“A church! Another church! A farm!”

The way Pols had played her first piece, “Vienna Blood,” had felt like a warning. Schumann’s “Träumerei” was also known as “Dreams of Childhood,” but in Pollina’s interpretation the dreams had been twisted and haunted. The girl’s preternatural ability was very like the young Mozart’s, and she wanted time to be able to develop it as he had. But she knew her body was turning against her, as Beethoven’s had. Though she would never say it out loud, she had been sending Sarah a clear message in her choice of pieces: Pols was perfectly aware of how sick she was. And she was anxious, and frightened.

* * *

A crackly “Wien Meidling” had announced her train’s arrival in Vienna. Sarah made her way outside the station to a queue of cabs, greeting the driver with the Austrian “Grüss Gott.” For her ride through the city that was the adopted home of Beethoven and Mozart, she had to listen to ’80s pop blaring on the car radio. Duran Duran’s “Hungry Like the Wolf,” then Gloria Estefan demanding party and siesta.

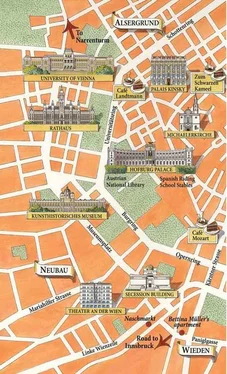

Vienna. Outside the window, low industrial buildings were gradually replaced by lovely edifices of stone, and curving boulevards bisected with tram tracks. Sarah was relieved to see how orderly, how expansive, how cosmopolitan and polished Vienna appeared. After the warren of Prague’s Easter egg–hued streets, Vienna looked refreshingly straightforward. Prague was a place where you could easily believe alchemists were lurking about. Vienna, although geographically farther east, had a decidedly Western European ambience. This was the kind of place where the frontiers of modern medicine were being pushed forward by scientists, not magicians. Sarah began to feel a surge of optimism. It was like Nico said. She wasn’t going to sit and do nothing. She was going to use her talents. No moping, no hand-wringing.

Her friend Alessandro’s apartment was located just outside the “Ring”—the wide boulevard that Emperor Franz Joseph had ordered built in 1857 to replace the old city walls and which now enclosed the historic center of Vienna.

“Bellissima!” exclaimed Alessandro, opening the door of his apartment to Sarah. The lanky and beautiful Italian was wearing an oddly cut dark green suit with leather piping and an Alpine hat, complete with feather. He planted a firm kiss on her lips and grabbed her ass.

“Ah, good,” he said. “So often the acquisition of the PhD is ruinous to the culo. But yours has survived intact. Congratulations, Frau Doktor Weston.”

“Danke,” Sarah said, giving Alessandro’s own perfectly formed culo a good swat. Sarah had heard signorina after signorina testify in operatic terms as to the quality of Alessandro’s lovemaking through the thin walls of their Boston apartment, but had never felt the urge to try it herself. Fortunately, Alessandro had not taken this as a challenge, and he treated Sarah as a sister—or, as he had once said, like a brother. Now he released her and ushered her into a tiny and immaculate living room.

Читать дальше