Sarah kept her tone light. “Let’s face it, I’m no princess.”

Pols absorbed this as she munched on a doughnut. The changes in the girl were dramatic, but Sarah found them difficult to assess. Was her friend older looking because she was in fact heading into full teenager status, or had her illness aged her prematurely? She was not much taller, still slight, but her face had definitely lost its doll-like roundness. She was moving slowly, but then Pols always moved slowly, unless she was playing the piano or violin, when she was capable of Dervish-like agility and Titanic power.

“I see you as a conductor,” Pols said at last, having demolished the doughnut. “When I’m done with my opera you should conduct it.”

“Was that what you were playing when I came in?”

“Yes. That was the theme.” Pols straightened her back. “The whole thing flows from those five notes, which are encrypted throughout the entire work. Or will be.”

“What’s your libretto?”

“I’m writing it myself. But I need to work fast. Mozart was twelve when he wrote Bastien und Bastienne and La finta semplice .”

“Well, those weren’t great operas.” But it’s good that she’s feeling competitive, Sarah thought. She’s a fighter.

“No, not truly great. They showed ambition but not compassion. The music was there, but emotionally he was still immature,” said Pols. “Like you, kind of.”

* * *

At noon, Sarah slipped into the back row of Lobkowicz Palace Museum’s Music Room. The 7th Prince Lobkowicz had been a major supporter of Ludwig van Beethoven. Word had apparently gotten around that the current Lobkowicz was patron to another extraordinary genius. The place was packed.

I’ll know how Pols really feels, Sarah thought, when I hear her play .

Harriet Hunter took the seat next to Sarah, togged out today in a green corduroy frock coat buttoned over a white silk blouse and green and black vest, with narrow black velvet pants. A sort of nineteenth-century cross-dressed look. You had to give the woman points for style.

“How are you feeling?” Harriet whispered, searching Sarah’s face. “After your plunge last night? Max said you were into the river before anyone else had sorted out what was happening. And you think someone was shooting at you?”

“I might have been mistaken about that,” Sarah said, hedging. “There was a lot going on.” So Max had told Harriet about the gunshots, even though Nico had counseled discretion?

“Max said you’re working on a book?” Sarah asked Harriet, hoping to steer the conversation away from drowning madmen and mysterious plots.

“A novel.” Harriet smiled. “Although it requires a great deal of research. My heroine is Elizabeth Weston—the poet? They called her ‘Westonia.’ No relation of yours, Max says.”

“Weston is a common name,” Sarah said, though the name Westonia had given her a bit of a jolt.

“In her day Elizabeth Weston was more famous than Shakespeare,” said Harriet. “I’m taking a bit of a risk, imagining her as a modern woman, looking back at her life and accomplishments here in Prague. But it’s atrocious she’s been so forgotten. I’m hoping to really make her come alive for a modern audience.”

“Sounds great,” said Sarah. Although in my experience, she thought, it’s not hard to make history come alive in Prague. The hard part is making history stay dead .

According to Nico, Westonia had been the name Tycho Brahe had given to one of his little alchemical experiments, the result of which had been a perception-expanding drug that both Sarah and Max had taken. Westonia allowed you to see the past, see it so clearly that it was like time traveling. Nico had said that Brahe had named the drug after Elizabeth Weston, though Sarah had no idea why. She wondered if Max had said anything to Harriet about it. Probably not. The whole thing was pretty hard to believe and anyway the ingredients for making it were all gone.

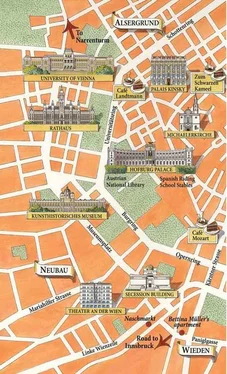

Harriet squinted at her program. Sarah wondered if she would take an eyeglass on a velvet ribbon from her waistcoat pocket. “What does dear Pollina have in store for us today?” Harriet murmured. “Oh God. Strauss. Well, we must endure. That’s for you, is it? I hear you’re off to Vienna. I admit I find Vienna something of a sphinx. You’ll meet quite a lot of them there. Sphinxes. And not just on buildings and lampposts.”

Sarah smiled politely.

“Oh, you are prepared,” Harriet laughed. “That was a very Viennese smile. Giving away nothing and concealing everything.”

Max came and sat down on the other side of Harriet, who took his hand. They make a nice couple, Sarah told herself sternly, hoping she wouldn’t be forced to make small talk, since at the sight of Max all her resolution dissolved and she had to admit there was just a tiny possibility that she might leap over Ms. Masterpiece Theatre and grab Max by his monogrammed wrists and tell him that—

Fortunately a hush fell over the room as a tall, silver-haired woman carrying a violin entered the Music Room, followed by Pols, walking slowly with one arm on a uniformed museum guard. The crowd instantly grew silent and attentive as the young girl seated herself at the piano and the violinist arranged her own music on a stand in front of her.

The first piece—“Vienna Blood” by Johann Strauss II—was perhaps better translated as “Vienna Spirit.” It was Vienna as it liked to think of itself: sprightly, charming, and sensual. But Pols seemed to be finding something else in the music, as if the charm of Vienna concealed something broken. She was giving the merry waltz an almost sinister quality, revealing a darker truth. Pollina then launched into Schumann’s “Träumerei,” a piece usually played slowly and introspectively. The young girl broke that convention immediately, handling the ascensions with a nervous and almost threatening pace. Next was Mozart’s Piano Sonata no. 14. The ease with which Pollina played this was breathtaking, but Sarah saw she was distracted. Her thin face occasionally broke into frowns or smiles, as if she were conducting a conversation with the composer, sometimes praising and sometimes scolding. The violinist and a teenage cellist wearing a yarmulke and a prayer shawl joined for the final offering: Luigi’s Piano Trio, op. 97. (Sarah always thought of Ludwig van Beethoven by his favorite nickname.) According to a contemporary account of Beethoven’s performance at the premiere, “In forte passages the poor deaf man pounded on the keys until the strings jangled, and in piano he played so softly that whole groups of notes were omitted.” It had marked Luigi’s last public performance as a pianist.

Pols was in the middle of the second movement when she started coughing. She tried valiantly to keep playing, but finally stopped, chest heaving.

Sarah and Max both ran down the aisle to help the girl to her feet.

“I’m sorry,” Pollina whispered.

“I’m going to find someone who can help you,” Sarah promised. She looked at Max over the girl’s head. His eyes said, Hurry.

Nicolas Pertusato was not in the best of spirits. This was annoying, since he had been imbibing the best of spirits for a long time now and should have been feeling more cheerful. Of course, plane travel was no more a comfortable experience for him than it was for people with less abbreviated statures. On the one hand, he had more leg room than most adults. On the other hand, he could not make use of the overhead bins without engaging a flight attendant, and there were no attractive ones on this particular flight to London. You had to fly to Dubai to get a shapely stewardess these days. Although the ones on Japan Air were still fairly delectable.

Читать дальше