“Is she here?” Sarah asked Nina. “Doktor Müller?” There were hundreds of people milling about. This was going to be difficult.

“She will be late,” Nina said. “She always is. In the meantime, you should enjoy yourself.”

Sarah was just hoping not to split a seam before Dr. Müller showed up.

Heinrich touched her shoulder. “Do not be offended,” he shouted over the din, “if no one outside of our group asks you to dance. It would violate tradition. People come in couples or groups, and it would be considered ill-mannered to prey on a member of someone else’s party, although ogling is allowed.” Heinrich ogled Sarah, as if to demonstrate its acceptability.

When the orchestra leader announced, “Meine Damen und Herren, alles Waltzer,” and “Tales from the Vienna Woods” began, Sarah begged Alessandro to let her just watch the dancing for a moment. Each couple made their own swirling little circle while at the same time the entire crowd swirled counterclockwise, like an elaborate clockwork mechanism with hundreds of gauzy, glinting, moving parts. It was beautiful, it was romantic, it was slightly absurd, and it was fabulous.

When Alessandro led her into the next dance, Sarah had a moment of panic as she tried to recall where her feet were supposed to be, and then, to her great surprise, she was doing it, waltzing. Not perfectly, but definitely waltzing. She had to splay out her toes to keep the shoes on, and had an ongoing fear that the laces holding in her bosom would snap and release the hounds, and yet it was fun. Alessandro handed her over to another university colleague, who was more precise, and her technique improved. Then she danced with Heinrich, whose hands were predictably sweaty. But still no sign of Bettina Müller.

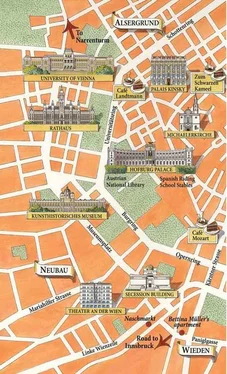

Marie-Franz suggested they go up to the gallery, where the view of the dancers would be particularly lovely. “ Vai . I will wait for Bettina,” said Alessandro. Sarah and Marie-Franz made their way to one of the grand staircases, a marble and wrought-iron affair with columns supporting pointed-arch vaults. Their progress up was slow, as Marie-Franz continually stopped to introduce Sarah to more people. On the mezzanine they looked down on the swirling couples in costume and Sarah tried to remind herself which century she was in. Taking out her cell phone to snap a few pictures helped.

“Adele!” Sarah turned and Marie-Franz introduced her to a man she named as Herr Kapellmeister Gerhard Schmitt, and then to his wife, Adele, a willowy blonde who clung briefly to Marie-Franz as the taller woman stooped to kiss her cheek. “Frau Doktor Weston joins us from Boston. She’s only just arrived.”

“Frau Doktor Weston, I kiss your hand. I hope our meager entertainment is not a bore,” said the man, as his wife rolled her eyes theatrically. Sarah couldn’t tell if the woman was unimpressed with the splendid scene or her husband. The Kapellmeister had a mane of very blond hair, and Sarah thought the name was familiar.

“Not at all,” said Sarah. “It’s—”

“In the regular season,” the blonde interrupted, “it is not uncommon for women to get fat injected into the balls of the feet, so they can dance all night long.” She spilled some of her drink on Sarah’s dirndl and lurched sideways into the professor. “I wish I had your sense of humor, Marie-Franz. I wish I could laugh it all away.”

Before the professor could respond to this, the man said, “Enjoy your evening,” and led his wife away, his eyes lingering on Sarah’s breasts.

“You recognized him perhaps?” asked Marie-Franz after the couple were out of earshot. “Gerhard Schmitt is a composer, and director of the Vienna Chamber Orchestra. He has taken the old title of Kapellmeister, though he is known in the press as ‘the Lion of Vienna’ on account of the hair. Ha! Adele is a harpist. I’ve known her since we were children. She’s not always so . . . unstable.”

“You seem to know everyone.”

“Oh, we’re terrible gossips here.” Marie-Franz laughed her infectious, booming laugh. “And it is more that everyone knows me! Not that I am famous. But you see, I used to be Herr Professor Franz Morgendal. And now—” Marie-Franz gestured modestly to her dirndled bosom and flipped up the ends of her thick, wheat-colored hair.

Sarah put the deep voice, the height, the hands, and the slight hint of Adam’s apple together.

“Some people think I should drop the Franz from my name, because it is confusing,” the professor explained. “But I just like the way Marie-Franz sounds .”

“It’s very musical,” Sarah agreed. “And why not please yourself?”

“ Yes! I did not take the hormones or do the surgeries so that I could make people uncomfortable or comfortable. I did it so that I could live my life as it was intended in my soul. Yes! I use the word ‘soul’ even though I am a professor of the history of science and in the history of science they have never proved the soul. Only its expression.”

Sarah raised her glass in salutation. She rarely used the word ‘soul’ herself, but she was definitely in kinship with living your life as you feel it was intended.

“Geniesse das Leben ständig! Du bist länger tot als lebendig!” said Marie-Franz, clinking glasses.

Constantly enjoy life! You’re longer dead than alive!

They returned to the main floor. A tall man, resplendent in a Tyrolean uniform, had joined their group and stood chatting with Nina and Heinrich. The man’s hair was dark, but his mustache and beard, groomed to a point, were red. His entire bearing and grandeur were very like the statue of the fifteenth-century Viennese notable he happened to be standing in front of.

“My brother, Gottfried,” said Heinrich. Gottfried bowed stiffly.

“Gottfried is a rider at our famous Spanish Riding School,” said Nina. “He’s also a terrible snob, so don’t expect him to ask you to dance.”

Gottfried looked at Nina coolly, then offered his arm to Sarah. By this time, Sarah felt as though she had had enough of the waltzing already. Her toes were aching, her ribs felt oddly numb, and she was anxious about the continuing no-show of Bettina Müller, but she took his arm.

Gottfried, Sarah noted as they danced, smelled like an intriguing combination of oiled leather and fresh hay. Her sensitive nose also picked up an interesting crackling energy. And the beard was very sexy. Under different circumstances, this would all be worth exploring (and it would be one way to get her mind off Max), but Sarah was at the ball to find Dr. Müller, not pick up hot guys, no matter how Tyrolean. Still, she tried making conversation with Gottfried, asking him about the Spanish Riding School.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I do not speak your language.”

“I’m speaking to you in German ,” Sarah pointed out.

“Yes. You are speaking German as the Germans do. The accent is unpleasant. You must learn to speak like an Austrian.” Sarah had noticed a difference herself, with Nina and Marie-Franz, but it was mostly intonation and cadence. They had understood her perfectly. Nina had been right; Gottfried was a snob.

As they pirouetted past Alessandro, she saw that he was now talking to a small brown-haired woman with enormous glasses. Bettina Müller at last? She got rid of Gottfried by claiming waltz-induced dehydration and asking if he would mind getting her something to drink, which he seemed to be able to follow without her resorting to mime. She moved quickly over to Alessandro and the woman.

“Frau Doktor Müller, please allow me to introduce my dear friend Frau Doktor Sarah Weston,” said Alessandro.

The woman’s small hand was quite strong. Her glasses obscured most of her delicate features and magnified her eyes strangely. “So nice to meet you,” said Sarah, flashing her most charming smile, the one she used for job interviews and talking her way out of speeding tickets.

Читать дальше