In this scenario, the kernel multitasks in such a way that many threads of execution appear to be running concurrently; however, the kernel is actually interleaving executions sequentially, based on a preset scheduling algorithm (see “Scheduling Algorithms”). The scheduler must ensure that the appropriate task runs at the right time.

An important point to note here is that the tasks follow the kernel’s scheduling algorithm, while interrupt service routines (ISR) are triggered to run because of hardware interrupts and their established priorities.

As the number of tasks to schedule increases, so do CPU performance requirements. This fact is due to increased switching between the contexts of the different threads of execution.

Each task has its own context, which is the state of the CPU registers required each time it is scheduled to run. A context switch occurs when the scheduler switches from one task to another. To better understand what happens during a context switch, let’s examine further what a typical kernel does in this scenario.

Every time a new task is created, the kernel also creates and maintains an associated task control block (TCB). TCBs are system data structures that the kernel uses to maintain task-specific information. TCBs contain everything a kernel needs to know about a particular task. When a task is running, its context is highly dynamic. This dynamic context is maintained in the TCB. When the task is not running, its context is frozen within the TCB, to be restored the next time the task runs. A typical context switch scenario is illustrated in Figure 4.3.

As shown in Figure 4.3, when the kernel’s scheduler determines that it needs to stop running task 1 and start running task 2, it takes the following steps:

1. The kernel saves task 1’s context information in its TCB.

2. It loads task 2’s context information from its TCB, which becomes the current thread of execution.

3. The context of task 1 is frozen while task 2 executes, but if the scheduler needs to run task 1 again, task 1 continues from where it left off just before the context switch.

The time it takes for the scheduler to switch from one task to another is the context switch time. It is relatively insignificant compared to most operations that a task performs. If an application’s design includes frequent context switching, however, the application can incur unnecessary performance overhead. Therefore, design applications in a way that does not involve excess context switching.

Every time an application makes a system call, the scheduler has an opportunity to determine if it needs to switch contexts. When the scheduler determines a context switch is necessary, it relies on an associated module, called the dispatcher, to make that switch happen.

The dispatcher is the part of the scheduler that performs context switching and changes the flow of execution. At any time an RTOS is running, the flow of execution, also known as flow of control, is passing through one of three areas: through an application task, through an ISR, or through the kernel. When a task or ISR makes a system call, the flow of control passes to the kernel to execute one of the system routines provided by the kernel. When it is time to leave the kernel, the dispatcher is responsible for passing control to one of the tasks in the user’s application. It will not necessarily be the same task that made the system call. It is the scheduling algorithms (to be discussed shortly) of the scheduler that determines which task executes next. It is the dispatcher that does the actual work of context switching and passing execution control.

Depending on how the kernel is first entered, dispatching can happen differently. When a task makes system calls, the dispatcher is used to exit the kernel after every system call completes. In this case, the dispatcher is used on a call-by-call basis so that it can coordinate task-state transitions that any of the system calls might have caused. (One or more tasks may have become ready to run, for example.)

On the other hand, if an ISR makes system calls, the dispatcher is bypassed until the ISR fully completes its execution. This process is true even if some resources have been freed that would normally trigger a context switch between tasks. These context switches do not take place because the ISR must complete without being interrupted by tasks. After the ISR completes execution, the kernel exits through the dispatcher so that it can then dispatch the correct task.

4.4.5 Scheduling Algorithms

As mentioned earlier, the scheduler determines which task runs by following a scheduling algorithm (also known as scheduling policy). Most kernels today support two common scheduling algorithms:

· preemptive priority-based scheduling, and

· round-robin scheduling.

The RTOS manufacturer typically predefines these algorithms; however, in some cases, developers can create and define their own scheduling algorithms. Each algorithm is described next.

Preemptive Priority-Based Scheduling

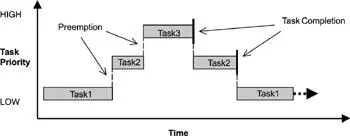

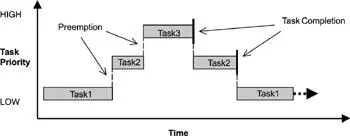

Of the two scheduling algorithms introduced here, most real-time kernels use preemptive priority-based scheduling by default. As shown in Figure 4.4 with this type of scheduling, the task that gets to run at any point is the task with the highest priority among all other tasks ready to run in the system.

Figure 4.4: Preemptive priority-based scheduling.

Real-time kernels generally support 256 priority levels, in which 0 is the highest and 255 the lowest. Some kernels appoint the priorities in reverse order, where 255 is the highest and 0 the lowest. Regardless, the concepts are basically the same. With a preemptive priority-based scheduler, each task has a priority, and the highest-priority task runs first. If a task with a priority higher than the current task becomes ready to run, the kernel immediately saves the current task’s context in its TCB and switches to the higher-priority task. As shown in Figure 4.4 task 1 is preempted by higher-priority task 2, which is then preempted by task 3. When task 3 completes, task 2 resumes; likewise, when task 2 completes, task 1 resumes.

Although tasks are assigned a priority when they are created, a task’s priority can be changed dynamically using kernel-provided calls. The ability to change task priorities dynamically allows an embedded application the flexibility to adjust to external events as they occur, creating a true real-time, responsive system. Note, however, that misuse of this capability can lead to priority inversions, deadlock, and eventual system failure.

Round-Robin Scheduling

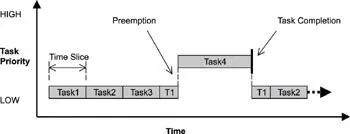

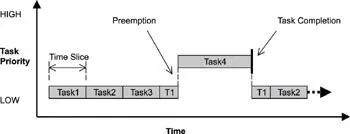

Round-robin scheduling provides each task an equal share of the CPU execution time. Pure round-robin scheduling cannot satisfy real-time system requirements because in real-time systems, tasks perform work of varying degrees of importance. Instead, preemptive, priority-based scheduling can be augmented with round-robin scheduling which uses time slicing to achieve equal allocation of the CPU for tasks of the same priority as shown in Figure 4.5.

Figure 4.5: Round-robin and preemptive scheduling.

With time slicing, each task executes for a defined interval, or time slice, in an ongoing cycle, which is the round robin. A run-time counter tracks the time slice for each task, incrementing on every clock tick. When one task’s time slice completes, the counter is cleared, and the task is placed at the end of the cycle. Newly added tasks of the same priority are placed at the end of the cycle, with their run-time counters initialized to 0.

Читать дальше