Joe Hill and Stephen King

THROTTLE

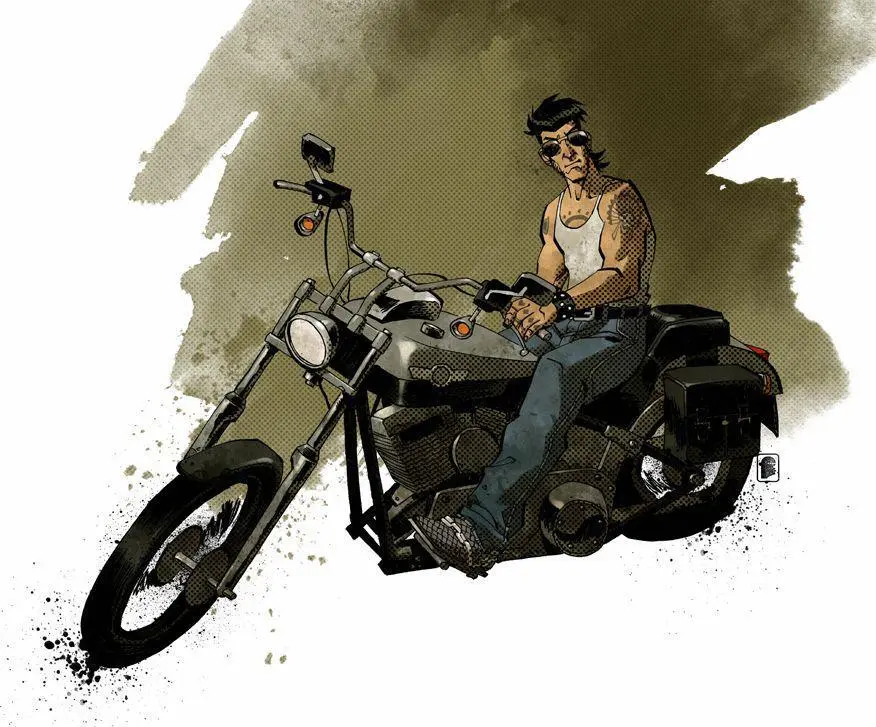

THEY RODE WEST FROM THE SLAUGHTER, through the painted desert, and did not stop until they were a hundred miles away. Finally, in the early afternoon, they turned in at a diner with a white stucco exterior and pumps on concrete islands out front. The overlapping thunder of their engines shook the plate-glass windows as they rolled by. They drew up together among parked long-haul trucks, on the west side of the building, and there they put down their kickstands and turned off their bikes.

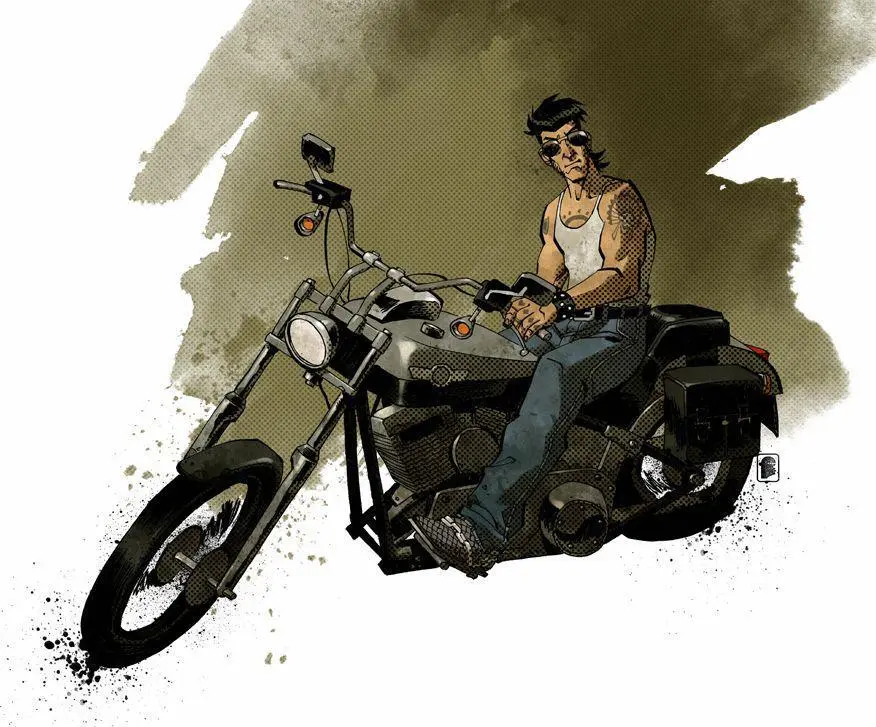

Race Adamson had led them the whole way, his Harley running sometimes as much as a quarter-mile ahead of anyone else’s. It had been Race’s habit to ride out in front ever since he had returned to them, after two years in the sand. He ran so far in front it often seemed he was daring the rest of them to try and keep up, or maybe had a mind to simply leave them behind. He hadn’t wanted to stop here but Vince had forced him to. As the diner came into sight, Vince had throttled after Race, blown past him, and then shot his hand left in a gesture The Tribe knew well: follow me off the highway . The Tribe let Vince’s hand gesture call it, as they always did. Another thing for Race to dislike about him, probably. The kid had a pocketful of them.

Race was one of the first to park but the last to dismount. He stood astride his bike, slowly stripping off his leather riding gloves, glaring at the others from behind his mirrored sunglasses.

“You ought to have a talk with your boy,” Lemmy Chapman said to Vince. Lemmy nodded in Race’s direction.

“Not here,” Vince said. It could wait until they were back in Vegas. He wanted to put the road behind him. He wanted to lie down in the dark for a while, wanted some time to allow the sick knot in his stomach to abate. Maybe most of all, he wanted to shower. He hadn’t gotten any blood on him, but felt contaminated all the same, and wouldn’t be at ease in his own skin until he had washed the morning’s stink off.

He took a step in the direction of the diner, but Lemmy caught his arm before he could go any farther. “Yes. Here.”

Vince looked at the hand on his arm—Lemmy didn’t let go; Lemmy of all the men had no fear of him—then glanced toward the kid, who wasn’t really a kid at all anymore and hadn’t been for years. Race was opening the hardcase over his back tire, fishing through his gear for something.

“What’s to talk about? Clarke’s gone. So’s the money. There’s nothing left to do. Not this morning.”

“You ought to find out if Race feels the same way. You been assuming the two of you are on the same page even though these days he spends forty minutes of every hour pissed off at you. Tell you something else, boss. Race brought some of these guys in, and he got a lot of them fired up, talking about how rich they were all going to get on his deal with Clarke. He might not be the only one who needs to hear what’s next.” He glanced meaningfully at the other men. Vince noticed for the first time that they weren’t drifting on toward the diner, but hanging around by their bikes, casting looks toward him and Race both. Waiting for something to come to pass.

Vince didn’t want to talk. The thought of talk drained him. Lately, conversation with Race was like throwing a medicine ball back and forth, a lot of wearying effort, and he didn’t feel up to it, not with what they were driving away from.

He went anyway, because Lemmy was almost always right when it came to Tribe preservation. Lemmy had been riding six to Vince’s twelve going back to when they had met in the Mekong Delta and the whole world was dinky dau . They had been on the lookout for trip wires and buried mines then. Nothing much had changed in the almost forty years since.

Vince left his bike and crossed to Race, who stood between his Harley and a parked truck, an oil hauler. Race had found what he was looking for in the hardcase on the back of his bike, a flask sloshing with what looked like tea and wasn’t. He drank earlier and earlier, something else Vince didn’t like. Race had a pull, wiped his mouth, held it out to Vince. Vince shook his head.

“Tell me,” Vince said.

“If we pick up Route 6,” Race said, “we could be down in Show Low in three hours. Assuming that pussy rice-burner of yours can keep up.”

“What’s in Show Low?”

“Clarke’s sister.”

“Why would we want to see her?”

“For the money. Case you hadn’t noticed, we just got fucked out of sixty grand.”

“And you think his sister will have it.”

“Place to start.”

“Let’s talk about it back in Vegas. Look at our options there.”

“How about we look at ’em now? You see Clarke hanging up the phone when we walked in? I heard a snatch of what he was saying through the door. I think he tried to get his sister, and when he didn’t, he left a message with someone who knows her. Now why do you think he felt a pressing need to reach out and touch that toe-rag as soon as he saw all of us in the driveway?”

To say his goodbyes was Vince’s theory, but he didn’t tell Race that. “She doesn’t have anything to do with this, does she? What’s she do? She make crank too?”

“No. She’s a whore.”

“Jesus. What a family.”

“Look who’s talking,” Race said.

“What’s that mean?” Vince asked. It wasn’t the line that bothered him, with its implied insult, so much as Race’s mirrored sunglasses, which showed a reflection of Vince himself, sunburnt and a beard full gray, looking puckered, lined, and old.

Race stared down the shimmering road again and when he spoke he didn’t answer the question. “Sixty grand, up in smoke, and you can just shrug it off.”

“I didn’t shrug anything off. That’s what happened. Up in smoke.”

Race and Dean Clarke had met in Fallujah—or maybe it had been Tikrit. Clarke, a medic specializing in pain management, his treatment of choice being primo dope accompanied by generous helpings of Wyclef Jean. Race’s specialties had been driving Humvees and not getting shot. The two of them had remained friends back in The World, and Clarke had come to Race a half a year ago with the idea of setting up a meth lab in Smith Lake. He figured sixty grand would get him started, and that he’d be making more than that per month in no time.

“True glass,” that had been Clarke’s pitch. “None of that cheap green shit, just true glass.” Then he’d raised his hand above his head, indicating a monster stack of cash. “Sky’s the limit, yo?”

Yo . Vince thought now he should have pulled out the minute he heard that come out of Clarke’s mouth. The very second.

But he hadn’t. He’d even helped Race out with twenty grand of his own money, in spite of his doubts. Clarke was a slacker-looking guy who bore a passing resemblance to Kurt Cobain: long blond hair and layered shirts. He said yo , he called everyone man , he talked about how drugs broke through the oppressive power of the overmind. Whatever that meant. He surprised and charmed Race with intellectual gifts: plays by Sartre, mix tapes featuring spoken-word poetry and reggae dub.

Vince didn’t resent Clarke for being an egghead full of spiritual-revolution talk that came out in some bullshit half-breed language, part Pansy and part Ebonics. What disconcerted Vince was that when they met, Clarke already had a stinking case of meth mouth, his teeth falling out and his gums spotted. Vince didn’t mind making money off the shit but had a knee-jerk distrust of anyone gamy enough to use it.

Читать дальше