“Well,” I said, “it looks as though we’ve talked ourselves into it.”

She gave a fleeting, humourless smile.

Later that afternoon, I telephoned Father Anton and told him what we were planning to do. He was silent for a long time on the other end of the line, and then he said, “I cannot persuade you otherwise?”

“Madeleine’s set on it, and I guess I am, too.”

“You’re not doing this out of a mistaken sense of affection for Madeleine? Because it can only do her harm, you know. You must realize that.”

I looked across the polished floor of Pont D’Ouilly’s post office, marked with muddy footprints where the local farmers had come in to draw their savings or to post their letters. There was a tattered poster on the wall beside me warning of the dangers of rabies. Outside, a thin wet snow was falling, and the sky was unremittingly grey.

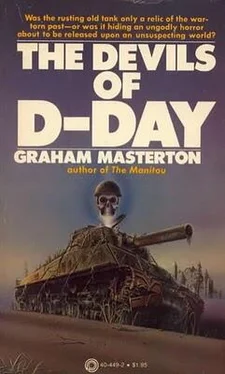

“It has to be done sometime, Father Anton. One day that tank’s going to corrode right through, and that demon’s going to get out anyway, and maybe someone completely unsuspecting is going to be passing by. At least we have some idea of what we’re in for.”

Father Anton was silent for even longer. Then he said hoarsely: “I’ll have to come with you, you know. I’ll have to be there. What time are you planning to do it?”

I glanced up at the post office clock. “About three. Before it gets too dark.”

“Very well. Can you collect me in your car?”

“You bet. And thank you.”

Father Anton sounded solemn. “Don’t thank me, my friend. I am only coming because I feel it is my duty to protect you from whatever lies inside that tank. I would far rather that you left it alone.”

“I know that, father. But I don’t think we can.”

He was waiting for me at the front door of his house, dressed in his wide black hat and black button-up boots, his cape as severe and dark as a raven. His housekeeper stood behind him and frowned at me disapprovingly, as if I was particularly selfish to take an old man out on an afternoon so cold and bleak—probably forgetting that it was colder inside his house than it was out. I helped him to climb into the front passenger seat, and smiled at the housekeeper as I walked around the car, but all she did was scowl at me from under her grubby lace cap, and slam the door.

As we drove off across the slushy grey cobbles of the priest’s front courtyard, Father Anton said, “Antoinette is what you probably call a fusspot. She believes she has divine instructions to make me wear my woollen underwear.”

“Well, I’m sure God cares about your underwear as much as He cares about anything else,” I told him, turning on the windshield wipers.

“My friend,” replied Father Anton, regarding me solemnly with his watery eyes, “God will take care of the spirit and leave the underwear to look after itself.”

It took us about ten minutes to drive the back way around the village to the Passerelle’s farm. The trees all around us were bare, and clotted with rooks’ nests; and the fields were already hazy and white with snow. I beeped the Citröen’s horn as we circled around the farmyard, and Madeleine came out of the door in a camel-hair duffel-coat, carrying an electric torch and an oily canvas bag full of tools.

I climbed out and helped her stow one kit away in the back of the car. She said, “I got everything. The crowbars, the hammers—everything you told me.”

“That’s good. What did your father say?”

“He isn’t so happy. But he says if we must do it, then we must. He’s like everyone else. They would like to see the tank opened, but they are too frightened to do it themselves.”

I glanced at Father Anton, sitting patiently in his seat. “I think that’s how the good father feels about it. He’s been dying to tackle this demon for years. It’s a priest’s job, after all. It just took a little coaxing.”

As I opened the door to let Madeleine into the back of the car, I heard Eloise calling from the kitchen. She came out into the dull afternoon, holding her black skirts up above the mud, and she was waving something in her hand.

“Monsieur! You must take this!”

She came nearer, and saw Father Anton sitting in the car, and nodded her head respectfully. “Good day, father.”

Father Anton raised a hand in courteous greeting.

Eloise came up close to me and whispered: “Monsieur, you must take this. Father Anton may not approve, so don’t let him see it. But it will help you against the creatures from hell.”

Into my hand, she pressed the same ring of hair that had been tied around the model cathedral in Jacques Passerelle’s parlour. I held it up, and said, “What is it? I don’t understand.”

Eloise glanced at Father Anton apprehensively, but the old priest wasn’t looking our way. “It is the hair of a firstborn child who was sacrificed to Moloch centuries ago, when devils plagued the people of Rouen. It will show the monsters that you have already paid your respects to them.”

I said: “I really don’t think—”

Eloise clutched my hands in her own bony fingers. “It doesn’t matter what you think, monsieur. Just take it.”

I slipped the ring of hair into my coat pocket, and climbed into the car without saying anything else. Eloise watched me through the snow-streaked window as I started up the motor, and turned the car around. She was still standing on her own in the wintry farmyard as we drove out of the gates and splashed our way through the melting slush en route to Pont D’Ouilly itself, and the tank.

Twisted into the hedgerow, the tank was lightly dusted with snow, and it looked more abandoned than ever. But we all knew what was waiting inside it, and as we got out of the Citröen and collected together the torch and the tools, none of us could keep our eyes off it.

Father Anton walked across the road, and took a large silver crucifix from inside his coat. In his other hand, he held a Bible, and he began to say prayers in Latin and French as he stood in the sifting snowflakes, his wide hat already white, with the low cold wind blowing the tails of his cape.

He then recited the dismissal of demons, holding the crucifix aloft as he did so, and making endless invisible crosses in the air.

“I adjure thee, O vile spirit, to go out. God the Father, in His name, leave my presence. God the Son, in His name, make thy departure. God the Holy Ghost, in His name, quit this place. Tremble and flee, O impious one, for it is God who commands thee, for it is I who command thee. Yield to me, to my desire by Jesus of Nazareth who gave His soul. To my desire by sacred Virgin Mary who gave Her womb, by the blessed Angels from whom thou fell. I demand thee be on thy way. Adieu O spirit, Amen.”

We waited for a while, shivering in the cold, while Father Anton stood with his head bowed. Then he turned to us, and said, “You may begin.”

Hefting the canvas bag of tools, I climbed up on to the tank’s hull. I reached back and helped Madeleine to scramble after me. Father Anton waited where he was, with the crucifix raised in one hand, and the Bible pressed to his breast.

I stepped carefully across to the turret. The maggots that I’d vomited yesterday had completely disappeared, as if they’d been nothing more than a rancid illusion. I knelt down and opened the canvas bag, and took out a long steel chisel and a mallet. Madeleine, kneeling beside me, said, “We can still turn back.”

I looked at her for a moment, and then I reached forward and kissed her. “If you have to face this demon, you have to face it. Even if we turn back today, we’ll have to do it sometime.”

I turned to the tank’s turret, and with five or six ringing blows, drove the edge of the chisel under the crucifix that was riveted on to the hatch. Thirty years of corrosion had weakened the bolts, and after five minutes of sweaty, noisy work, the cross was off. Then, just to make sure, I hammered the last few legible words of the holy adjuration into obscurity.

Читать дальше