Then whatever lay beyond it would be pristine. A Draconean site, wholly untouched since ancient times.

I got to my feet, then helped Suhail up. He was still staring at the wall, hardly blinking. I licked my lips, swallowed, then inhaled deeply and said, “I for one am very eager to know what is beyond that door.”

Tom looked to Suhail, but my husband seemed to have lost the power of speech. “Well?” Tom asked. “Will it damage anything if we force the door open?”

The question brought Suhail to rationality once more. “It might,” he said, in a shallow, cautious voice. “From the sound, I think the mechanism is stone and bronze, which is why it survived; wood or rope would have snapped at the first pressure. But it is not working smoothly any longer. We may not be able to close the door again.”

Then he blinked and drew what I think was his first real breath since he returned from his prayers. “Whatever we find in there,” he said, fixing each of us with his gaze, “we must not touch it. No matter what it may be. We may look only. Then we will close the door if we can, and go back to Qurrat, before this treasure lures us into stupidity or starvation.”

“Or both.” I reminded myself to keep breathing. It was remarkably easy to forget. “All of this, of course, presupposes we can get the door open.”

Tom and Andrew put their shoulders to it, both of them being stronger than Suhail. The panel made very unpleasant noises as it moved, but move it did. The wall proved to be approximately twenty centimeters thick, and beyond it was darkness. When the gap was large enough for my hand, I put a match through, as Suhail had done at the staircase, to test the air.

His voice trembling, he asked, “Can you see anything?”

“No,” I said. “Not from only a match’s flame. But the air is good.”

The men redoubled their efforts. Soon, however, the door ground to a halt… and the gap it left was not very large.

Andrew made an anguished noise. “We can’t just leave it like this! To hell with the mural—do we have a hammer? We could smash the edges off—”

“No!” Suhail yelped.

I stepped up to the crack and measured myself against it. “I think I can fit through. It will be tight, but possible.”

I should not have looked at my husband when I said that. His expression was that of a man who has glimpsed Paradise, and been told he may not enter. Contrition gripped my heart: as tremendous as this moment was for me, of the two of us, I was not the archaeologist. How would I feel if he went on to see some new kind of dragon, while I stayed behind? “Never mind,” I said. “It has waited this long; it can wait a while longer.”

“No,” Suhail said again, this time in a softer voice. “We cannot leave without knowing, and I will not destroy this door just to see. If you can fit through, then go.”

Tom sighed when I turned to him. “I would say, Do you think that’s safe? —but I know what your answer would be. If this turns out to lead into the back end of a drake’s lair, though, please do think twice before settling down to sketch it.”

Andrew said only, “You are both my most favourite and least favourite sister in the world right now.”

I was, of course, his only sister. Squaring my shoulders, I addressed the task of sliding through that narrow gap.

I had to exhale completely to fit through, and lost a button even so. It was a tight enough squeeze that I suffered a moment of worry as to what would happen if I got stuck. But then I was through, and Suhail passed along my notebook and pencil and one of the lamps. Before handing me the latter, he took my hand and kissed it, his body blocking this from the sight of the others. In a voice meant only for me, he murmured, “Come back and tell me of wonders.”

“I will,” I said, and turned to face the next step.

I was in a narrow corridor, running parallel to the wall. Suhail had been right; the hidden chamber lay back in the direction of the entrance. Not far ahead, the passage descended in another staircase, to a level below that of the previous room. By my calculation, the lower level must be at least halfway down the plateau.

For the sake of my companions, I called these details out to them. “There are murals here, too,” I said. “Painted, like the ones in the room, not the plain ones in the first corridor. All of gods—there are no human or dragon figures here that I can see.” A mischievous impulse seized me, and I added, “Shall I stay and draw them, before continuing on?”

The chorus of “No!” from behind me bid fair to shake dust from the ceiling, but it also made me smile and fortified me for the mystery ahead. When I raised my lamp, my hand no longer shook.

At the base of the steps, the corridor turned right again. Here, however, there was no door. The moment I rounded the corner, my lamp threw its light forward, and the chamber returned it in glory.

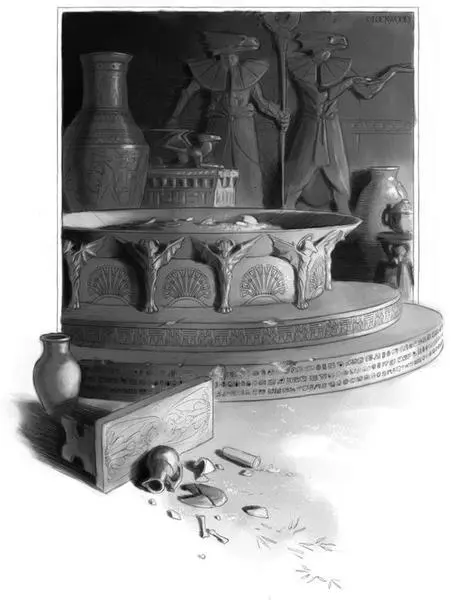

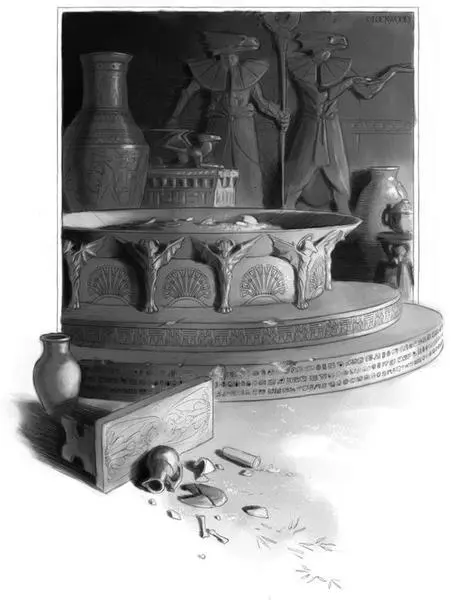

Even in its heyday, the hatching pit on Rahuahane must have been a rough, provincial thing. What I saw here was the exemplar: a square chamber carved and painted in the finest detail, with steps in the center leading up to a low, round platform. Unlike the room above, this one was still furnished. There were tables, stands, vases and bowls; gold and alabaster, coloured enamel and precious wood… an immeasurable treasure of unbroken Draconean artifacts.

Almost unbroken. One of the low tables had been upset, its dishes knocked to the floor. When I advanced into the room, I understood why.

Empty fragments of eggshell lay in the sand-lined center of the pit. There were no skeletons: of course there would not be. Those would have fallen to dust after the hatchlings died. Stains and a few bones from what looked like birds remained in or around some of the dishes; undoubtedly the ravenous newborns had devoured every scrap they could while they waited for their caretakers to return. Left alone, hunting for more sustenance, one of them must have knocked over the table. But the bottle atop it had held some kind of oil, not food, and its contents had spilled out to soak the bare earthen floor.

My lamplight fell upon marks pressed into the earth.

They were tracks. Footprints, left behind by the newly hatched dragons, as they wandered back and forth in search of food that would never come.

THE HATCHING CHAMBER

Later on, I was objective. I drew the tracks, measured them, took casts and tried to work out how many different individuals had trodden in that patch of oil-soaked ground. They were a priceless scientific discovery, and I valued them as such.

In that moment, however, I was not objective in the least. I envisioned the history that had transpired here—little hatchlings abandoned on the day of rebellion, starving to death in this beautiful and lifeless chamber—and I wept, tears rolling silently down my face. The Draconeans had never truly been people to me, only an ancient civilization who worshipped and bred dragons and therefore posed some intriguing puzzles. But the bodies up above had been people, individual men who lived and died; and the tracks here told the story of lives that had vanished without any other trace. Whatever had happened in the Labyrinth of Drakes, so many ages ago, it had carried a dreadful cost.

I do not know how long I stood there, my tears drying on my face. After a while the thought came to me that I was wasting precious water, crying like that; and so I came back to my senses. I hurried to the foot of the stairs and called up, “Are you still there?”

Suhail’s answer was impatient, disbelieving, and full of love. “Where do you think we would have gone?”

Читать дальше