Marie Brennan

A STAR SHALL FALL

Mortals

Those marked with an asterisk are attested in history.

Galen St. Clair — a gentleman, and Prince of the Onyx Court

Charles St. Clair — a gentleman of good name and poor fortune; Galen’s father

Cynthia St. Clair — a young lady in need of a dowry; Galen’s sister

Philadelphia Northwood — a young lady of great wealth

Jonathan Hurst}

Laurence Byrd} — friends to Galen St. Clair

Peter Mayhew}

Dr. Rufus Andrews — a physician and scholar; Fellow of the Royal Society

*George Parker, Earl of Macclesfield — President of the Royal Society, and architect of the new calendar

*Henry Cavendish — a brilliant young scholar; son of Lord Charles Cavendish

*James Bradley — Astronomer Royal to King George II

*Charles Messier — a French astronomer

*John Flamsteed — the first Astronomer Royal, now deceased

*Edmond Halley — a cometary astronomer and Fellow of the Royal Society, now deceased

*Sir Isaac Newton — former President of the Royal Society, now deceased

*Dr. Samuel Johnson — a learned gentleman of very strong opinions

*Elizabeth Vesey}

*Elizabeth Montagu} — ladies of the Bluestocking Circle

*Elizabeth Carter}

Edward Thorne — valet to Galen St. Clair

*Kitty Fisher — a courtesan

Sir Michael Deven}

Dr. John Ellin} — former Princes of the Stone, now deceased

Lord Joseph Winslow}

Dr. Hamilton Birch}

Faeries

Lune — Queen of the Onyx Court

Valentin Aspell — Lord Keeper

Amadea Shirrell — Lady Chamberlain

Sir Peregrin Thorne — Captain of the Onyx Guard

Sir Cerenel — Lieutenant of the Onyx Guard

Dame Segraine — a lady knight of the Onyx Guard

Dame Irrith — a sprite, and lady knight of the Vale of the White Horse

Carline — an elf-lady, now fallen from grace

Rosamund Goodemeade — a helpful brownie

Gertrude Goodemeade — likewise a helpful brownie, and Rosamund’s sister

Savennis — a courtier of scholarly inclinations

Wrain — a sprite, likewise scholarly

Magrat — a church grim

Hafdean — keeper of the Crow’s Head

Angrisla — a nightmare

Podder — a hob, and servant to the Princes of the Stone

Blacktooth Meg — hag of the River Fleet

Ktistes — a centaur, grandson of Kheiron

Wilhas von das Ticken — a good-tempered dwarf

Niklas von das Ticken — an ill-tempered dwarf; Wilhas’ brother

Lady Feidelm — an Irish sidhe, and former seer

Abd ar-Rashid — a genie of Istanbul

Il Veloce — a faun long resident in the Onyx Hall

Wayland Smith — King of the Vale of the White Horse in Berkshire

Invidiana — former Queen of the Onyx Court, now deceased

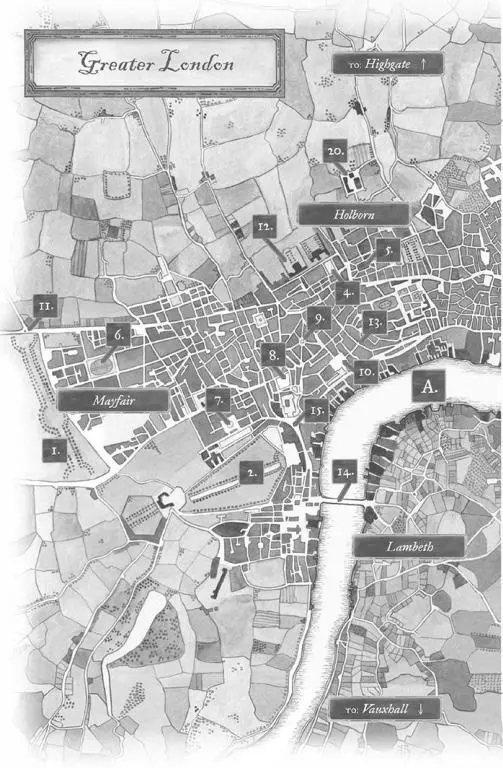

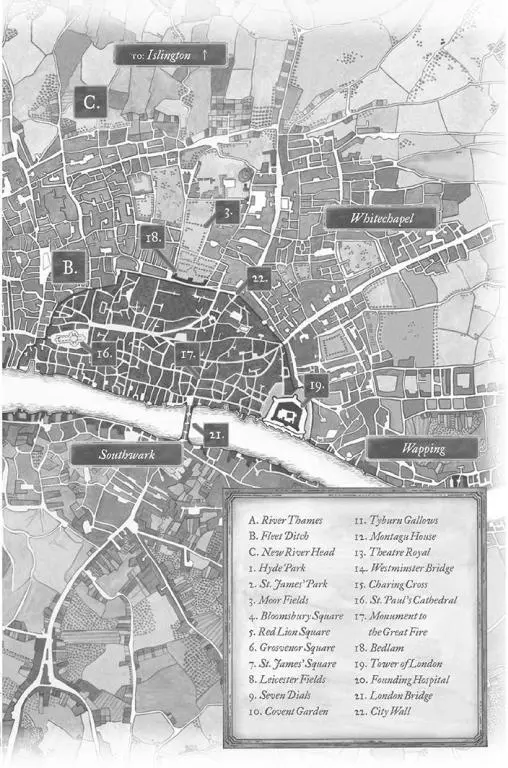

GRESHAM COLLEGE, LONDON

20 June 1705

The room was a shabby one to contain the intellectual brilliance of England. Small and scant of windows, it was nearly unbearable in the warmth of an early summer day, and filled with gentlemen looking forward to the pleasanter air of their country estates, away from the stinks of London. Some listened with interest to the letters being read, an exchange between two of their fellows regarding the island of Formosa; others fanned themselves futilely with whatever papers came to hand, wishing they dared nod off. But the gimlet eye of their president was upon them, and though Sir Isaac Newton might be more than sixty years old, age had not slowed him in the least, nor dulled the sharp edge of his tongue.

They gave an impression of agreeable uniformity in their somber-colored coats, so very different from the young gallants of London’s beau monde who took every opportunity to quarrel. Nothing could be further from the truth. Nullius in verba was their motto: on the words of no one. This was the temple of facts, of careful observation and even more careful reasoning; the men of the Royal Society of London, the premier scientific body of the Kingdom of England, were no respecters of ancient authority. They respected only Truth. And when they found themselves in disagreement as to what that Truth was, their arguments could grow very heated indeed.

But there was little to argue in the second piece of that day’s business, presented by Oxford’s new Savilian Professor of Astronomy. In all honesty, hardly any men there had the capacity to debate it; the proof hinged on Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica , which fewer of them understood than pretended to. Edmond Halley’s calculus therefore meant little to them. The fundamental point, however, was clear.

The orbit of a comet was not a parabola, but an ellipsis. And that meant that a comet, having departed from view, would in the fullness of time return.

A point that held rather a high degree of interest for two members of Halley’s audience.

“The measurements made by Flamsteed at Greenwich in 1682 are exceptionally precise,” the professor said, with a nod that acknowledged the contributions of the absent Astronomer Royal. “They provide us with a basis for examining the less-precise accounts of cometary apparitions in the past—1607, 1531, 1456, and so on.”

Back to the days of the Stuart kings, and the Tudors, and the Lancastrians. Many here today remembered the comet twenty-three years before, but a man’s beard would have to be gray indeed for him to have seen any of the others Halley named.

The one member of his audience who could claim that distinction had no beard at all. He was a young gallant more often found haunting the halls of London’s fencing masters, and his friends would have been surprised to see him in such sober costume, attending with hawklike intensity to the dull minutiae of astronomical mathematics.

Though not half so surprised as they would have been, had they ever seen their friend’s true face.

“A question, if you please,” the gallant said, interrupting Halley’s presentation of his Astronomiae cometicae synopsis , and drawing a swift frown from Newton. “Could anything divert the comet from its path?”

The Savilian Professor’s well-rehearsed presentation faltered. “I beg your pardon?”

“You say the comet travels far away from the sun, returning only every seventy-five years, or seventy-six. Could anything prevent that return, sending it out into space?”

Halley’s mouth opened and shut several times without anything coming out. “I suppose,” he said at last, with bewildered uncertainty, “that a large mass might exert gravitational force upon the cometary body, perturbing its path such that the return would not occur as expected. But to make it depart entirely… why, sir, would you be concerned with such a thing?”

Читать дальше