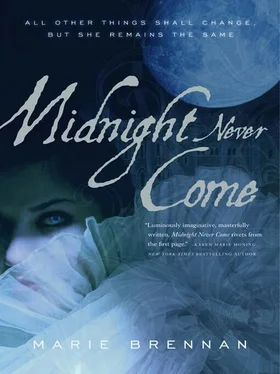

Marie Brennan

MIDNIGHT NEVER COME

This book is dedicated to two groups of people.

To the players of Memento: Jennie Kaye, Avery Liell-Kok, Ryan Conner, and Heather Goodman.

And to their characters, whose ghosts still haunt this story: Rowan Scott, Sabbeth, Erasmus Fleet, and Wessamina Hammercrank.

THE TOWER OF LONDON: March 1554

Fitful drafts of chill air blew in through the cruciform windows of the Bell Tower, and the fire did little to combat them. The chamber was ill lit, just wan sunlight filtering in from the alcoves and flickering light from the hearth, giving a dreary, despairing cast to the stone walls and meager furnishings. A cheerless place — but the Tower of London was not a place intended for cheer.

The young woman who sat on the floor by the fire, knees drawn up to her chin, was pale with winter and recent illness. The blanket over her shoulders was too thin to keep her warm, but she seemed not to notice; her dark eyes were fixed on the dancing flames, morbidly entranced, as if imagining their touch. She would not be burned, of course; burning was for common heretics. Decapitation, most likely. Perhaps, like her mother, she would be permitted a French executioner, whose sword would do the work cleanly.

Presuming the Queen’s mercy permitted her that consideration. Presuming the Queen had mercy for her at all.

The few servants she kept were not there; in a rage she had sent them away, arguing with the guards until she won these private moments for herself. As much as solitude oppressed her, she could not bear the thought of companionship in this dark moment, the risk of showing her weakness to others. And so when she waked from her reverie to sense another in the room, her anger rose again. Shedding the blanket, the young woman whirled to her feet, ready to confront the intruder.

Her words died, unspoken, and behind her the fire dipped low.

The woman she saw was no serving-maid, no lady attendant. No one she had ever seen before. A mere silhouette, barely visible in the shadows — but she stood in one of the alcoves, where a blanket had been tacked up to cover the arrow-slit window.

Not by the door. And she had entered without a sound.

“You are the Princess Elizabeth,” the woman said. Her voice was a cool ghost, melodious, soft, and dark.

Tall, she was, taller than Elizabeth herself, and more slender. She wore a sleek black gown, close-fitting through the body but flaring outward into a full skirt and a high standing collar that gave her presence weight. Jewels glimmered with dark color here and there, touching the fabric with elegance.

“I am,” Elizabeth said, drawing herself up to the dignity of her full height. “I have given no orders to accept visitors.” Nor was she permitted any, but in prison as in court, bravado could be all.

The stranger’s voice answered levelly. “I am not a visitor. Do you think this solitude your own doing? The guards allowed it because I arranged that they should. My words are for your ears alone.”

Elizabeth stiffened. “And who are you, that you presume to order my life in such fashion?”

“A friend.” The word carried no warmth. “Your sister means to execute you. She cannot risk your survival; you are a focal point for every Protestant rebellion, every disaffected nobleman who hates her Spanish husband. She must dispose of you, and soon.”

No more than Elizabeth herself had already calculated. To be here, in the stark confines of the Bell Tower, was an insult to her rank. Prisoner though she was, she should have received more comfortable lodgings. “No doubt you come to offer me some escape from this. I do not, however, converse with strangers who intrude on me without warning, let alone make alliances with them. Your purpose might be to lure me into some indiscretion my enemies could exploit.”

“You do not believe that.” The stranger came forward one step, into a patch of thin, gray light. A cruciform arrow-slit haloed her as if in painful mimicry of Heaven’s blessing. “Your sister and her Catholic allies would not treat with one such as I.”

Slender as a breath, she should have been skeletal, grotesque, but far from it; her face and body bore the stamp of unearthly perfection, a flawless symmetry and grace that unnerved as much as it entranced. Elizabeth had spent her childhood with scholars for her tutors, reading classical authors, but she knew the stories of her own land, too: the beautiful ones, the Fair Folk, the Good People, whose many epithets were chosen to mollify their capricious natures.

The faerie was a sight to send grown women to their knees, and Elizabeth was only twenty-one. Since childhood, though, the princess had survived the tempests of political unrest, riding from her mother’s inglorious downfall to her own elevation at her brother’s hands, only to plummet again when their Catholic sister took the throne. She was intelligent enough to be afraid, but stubborn enough to defy that fear, to cling to pride when nothing else remained.

“Do you think me easier to cozen than my sister? Some say your kind are fallen angels, or in league with the devil himself.”

The woman’s laugh echoed from the chamber walls like shattering crystal. “I do not serve the devil. I offer you a bond of mutual aid. With my help, you may be freed from the Tower and raised to your sister’s throne. Your father’s throne. Without it, your life will surely end soon.”

Elizabeth knew too much of politics to even consider an offer without hearing it in full. “And in return? What gift — no doubt a minor, insignificant trifle — would you require from me?”

“Oh, ’tis not minor.” The faintest of smiles touched the stranger’s lips. “As I will raise you to your throne, you will raise me to mine. And when we both achieve power, perhaps we will be of use to each other again.”

Every shrewd instinct and fiber of caution in Elizabeth warned her against this pact. Yet over her hovered the specter of death, the growing certainty of her sister’s bitterness and hatred. She had her allies, surely enough, but they were not here. Could they be relied upon to save her from the headsman?

To cover her thoughts, she said, “You have not yet told me your name.”

The fae paused. At last, her tone considering, she said, “Invidiana.”

When Elizabeth’s servants returned soon after, they found their mistress seated in a chair by the fire, staring into its glowing heart. The air in the chamber was freezing cold, but Elizabeth sat without cloak or blanket, her long, elegant hands resting on the arms of the chair. She was quiet that day, and for many days after, and her gentlewomen worried for her, but when word came that she was to be permitted to walk at times upon the battlements and to take the air, they brightened. Surely, they hoped, their futures — and that of their mistress — were looking up at last.

Time stands still with gazing on her face, stand still and gaze for minutes, houres and yeares, to her giue place: All other things shall change, but shee remains the same, till heauens changed haue their course & time hath lost his name.

— John Dowland

The third and last booke of songs or aires

No footfalls disturb the hush as the man — not nearly so young as he appears — passes down the corridor, floating as if he walks on the shadows that surround him.

His whisper drifts through the air, echoing from the damp stone of the walls.

“She loves me… she loves me not.”

His clothes are rich, thick velvet and shining satin, black and silver against pale skin that has not seen sunlight for decades. His dark hair hangs loose, not disciplined into curls, and his face is smooth. As she prefers it to be.

Читать дальше