Marie Brennan

VOYAGE OF THE BASILISK

A MEMOIR BY LADY TRENT

Depending upon your temperament, you may be either pleased or puzzled to see that I have chosen to include my time upon the Basilisk in my memoirs. It was, of course, a lengthy period in my life, totaling nearly two years in duration, and the discoveries I made in that time were not insignificant, nor were the effects of that journey upon my personal life. Seen from that perspective, it would seem odd were I to pass it by.

But those of you who are puzzled have good cause. Those two years are, after all, the most thoroughly documented period in my life. My contract with the Winfield Courier to provide them with regular reports meant that a great many in Scirland were kept apprised of my doings—quite apart from the reports that were written about me by others. Furthermore, my travelogue was later collected and printed as Around the World in Search of Dragons, and that title is still readily available from the publisher. Why, then, should I trouble to tell a story which is already so widely known?

Apart from the oddity of glossing over so major a period in my life, I have several reasons. The first is that my essays in the Winfield Courier were heavily skewed toward matters of exotic novelty, which was, after all, what their readers wanted to hear, though not the most apt depiction of my own experiences. Another is that I said little there of my personal affairs, and as a memoir is expected to be more personal, this is the ideal place to provide those elements which I excluded before.

But above all, this volume is intended to set the record straight, for part of what I said in those essays is an outright lie.

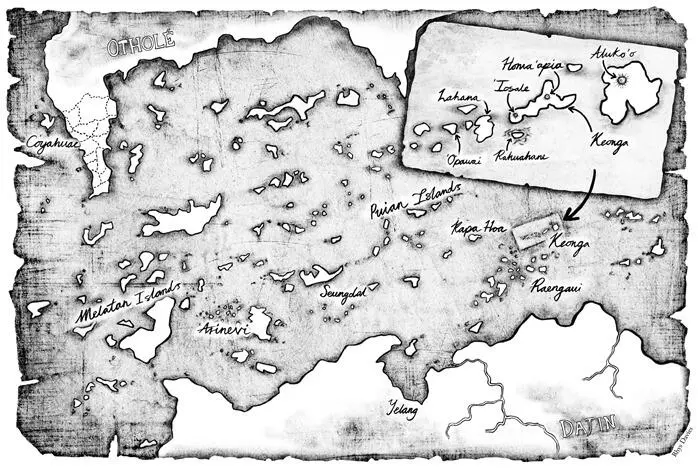

When I wrote to the Winfield Courier that I swam to Lahana after my adventure with the sea-serpent, and that during the excitement which followed I took a knock to the head and had to be sent to Phetayong to convalesce, not a word of it was true. I wrote those lines because I had no choice: my lengthy silence (which had persuaded a great many people back home that I was dead at last) must be broken with some kind of tale, and I could not give the honest one. Even had I wished to make public everything I had done, a high-ranking officer in His Majesty’s Royal Navy had forbidden me to do so. Indeed, it is only with some effort now that I have persuaded certain government officials to change their minds—now, so many years later, when a new dynasty rules in Yelang and the events in question are no longer of any particular political relevance.

But they have granted their permission, and so at last I may tell the truth. I will not attempt to recount every day of my journey aboard the Basilisk ; two years will not fit into one slim volume without substantial abridgement, and there is no point in repeating what I have said elsewhere. I shall instead focus on those portions which are either personal (and therefore new) or necessary to understanding what occurred at the end of my island sojourn.

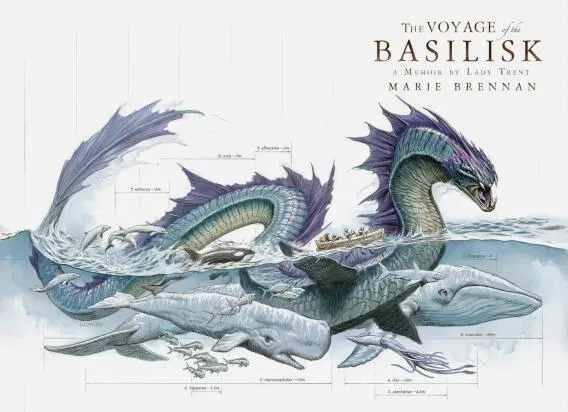

All in good time, of course. Before the truth comes out, you will hear of Jacob and Tom Wilker; Heali’i and Suhail; and Dione Aekinitos, the mad captain of the Basilisk . You will also hear of wonders terrestrial and aquatic, ancient ruins and modern innovations, mighty storms, near drownings, the rigors of life at sea, and more kinds of dragon than you can shake a wing at. Though there is a great deal I will omit here, I will endeavour to make my tale as complete and engaging as I may.

Isabella, Lady Trent Casselthwaite, Linshire 3 Seminis, 5660

In which the memoirist embarks upon her voyage

Life in Falchester—Abigail Carew—A meeting of the Flying University—M. Suderac—Galinke’s messenger—Skin conditions

At no point did I form the conscious intention of founding an ad hoc university in my sitting room. It happened, as it were, by accident.

The process began soon after Natalie Oscott became my live-in companion, having been disowned by her father for running away to Eriga. My finances could not long support the two of us in my accustomed style, especially not with my growing son to consider. I had to surrender some portion of my life as it had been until then, and since I was unwilling to surrender my scholarship, other things had to go.

What went was the house in Pasterway. Not without a pang; it had been my home for several years, even if I had spent a goodly percentage of that time in foreign countries, and I had fond memories of the place. Moreover, it was the only home little Jacob had known, and I did question for some time whether it was advisable to uproot so young a boy, much less to transplant him into the chaotic environment of a city. It was, however, far more economical for us to take up residence in Falchester, and so in the end we went.

Ordinarily, of course, city life is far more expensive than rural—even when the “rural” town in question is Pasterway, which nowadays has become a direct suburb of the capital. But much of this expense assumes that one is living in the city for the purpose of enjoying its glittering social life: concerts and operas, art exhibitions and fashion, balls and drums and sherry breakfasts. I had no interest in such matters. My concern was with intellectual commerce, and in that regard Falchester was not only superior but much cheaper.

There I could make use of the splendid Alcroft lending library, now better known as one of the foundational institutions of the Royal Libraries. This saved me a great deal of expense, as my research needs had grown immensely, and to purchase everything I required (or to send books back to helpful friends via the post) would have bankrupted me in short order. I could also attend what lectures would grant a woman entrance, without the trouble of several hours’ drive; indeed, I no longer needed to maintain a carriage and all its associated equipment and personnel, but rather could hire one as necessary. The same held true for visits with friends, and here it is that the so-called “Flying University” began to take shape.

The early stages of it were driven by my need for a governess. Natalie Oscott, though a good companion to me, had no wish to take on the responsibility of raising and educating my son. I therefore cast my net for someone who would, taking pains to specify in advance that my household was not at all a usual one.

The lack of a husband was, for some applicants, a selling point. I imagine many of my readers are aware of the awkward position in which governesses often find themselves—or rather, the awkward position into which their male employers often put them, for it does no one any service to pretend this happens by some natural and inexorable process, devoid of connection with anyone’s behaviour. My requirements for their qualifications, however, were off-putting to many. Mathematics were unnecessary, as Natalie was more than willing to tutor my son in arithmetic, algebra, and geometry (and would, by the time he was ready for calculus, have taught it to herself), but I insisted upon a solid grounding in literature, languages, and a variety of sciences, not to mention the history not only of Scirland but other countries as well. This made the process of reviewing applicants quite arduous. But it paid an interesting dividend: by the time I hired Abigail Carew, I had also made the acquaintance of a number of young ladies who lacked sufficient learning, yet possessed the desire for it in spades.

Читать дальше