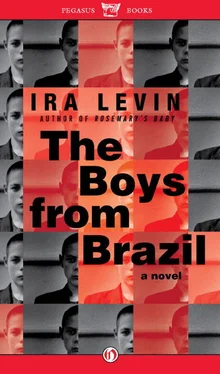

When the job was done, and the long table with its neat stacks of journals in place against the wall, Mengele could lean back in his steel-and-leather chair and admire the very chart he had envisioned. The ninety-four names, each with its country, date, and square box as if for balloting, were set out in three columns, the middle one of necessity a name longer than the two outer ones (a small annoyance, but what could be done at this late date?). There they all were, from 1. Döring—Deutschland—16/10/74  to 94. Ahearn—Kanada—23/4/77

to 94. Ahearn—Kanada—23/4/77  . How he looked forward to filling in each of those boxes! He would do that himself, of course, with either red or black paint, he hadn’t yet decided which. Perhaps he would try making checks, and if the first few didn’t turn out uniformly, then fill in the boxes.

. How he looked forward to filling in each of those boxes! He would do that himself, of course, with either red or black paint, he hadn’t yet decided which. Perhaps he would try making checks, and if the first few didn’t turn out uniformly, then fill in the boxes.

He swung in his chair and smiled at the Führer. You don’t mind being moved to the side for this, do you, my Führer? Of course not; how could you?

Then, alas, there had been nothing to do but wait—till the first of November, when the calls would come in to headquarters.

He had busied himself in the laboratory, where he was trying, not very enthusiastically, to transplant chromosomes in frog-cell nuclei.

He flew into Asunción one day; visited his barber and a prostitute, bought a digital clock, had a good steak at La Calandria with Franz Schiff.

And now, at last, the day had come—a fine one, so blinding-bright that he had drawn the study curtains. The radio was on and tuned to the headquarters frequency, with the earphones lying ready beside a memo pad and pen. On a corner of the desk’s glass top a white linen towel was laid out; on it, in surgical line-up, were a small unopened can of red enamel, a screwdriver, a new thin short-bristled paintbrush, a coverless petri dish, and a screw-top can of turpentine. The left end of the long table had been drawn from the wall; a stepladder waited before the first column of names and countries.

He had decided to try the checks.

Shortly before noon, when he was beginning to get quite impatient, the drone of a plane came with increasing loudness through the curtains. The drone of the headquarters plane—which meant either very good or very bad news. He hurried from the study, through the hall, and out onto the porch, where a few servants’ children sat breaking up a flat cake of some kind. He stepped over them and went around the side of the house to the back and down the few steps. The plane was just dropping behind treetops. Shielding his eyes, he hurried across the yard—a servant stopped leaning, started hoeing—and past the servants’ house and the barracks and the generator shed. Jogging, he entered the greened-over pathway cut through thick jungle foliage. He could hear the plane landing. He slowed to a fast walk, tucked the back of his shirt down into his trousers, got out his handkerchief and wiped his brow and cheeks. Why the plane, why not the radio? Something had gone wrong; he was sure of it. Liebermann? Had that filth somehow managed to end everything? If he had, he himself would personally go to Vienna and find and kill him. What else would he have left to live for?

He came out onto the side of the grass airstrip in time to see the red-and-white twin-engine plane rolling slowly toward his own smaller silver-and-black one. Two of the guards were lounging there with the pilot, who waved at him. He nodded. Another guard was across the strip at the chain-link fence, holding something through it, trying to lure an animal. Against rules, but he didn’t call out to him; he watched the door of the red-and-white plane, stopped now, propellers dying. Silently prayed.

The door swung down, and one of the guards trotted over to help a tall man in a light-blue suit down the steps.

Colonel Seibert! It had to be bad news.

He started forward slowly.

The colonel saw him, waved—cheerfully enough—and came toward him. He was carrying a red shopping bag.

Mengele walked faster. “News?” he called.

The colonel nodded, smiling. “Yes, good news!”

Thank God! He speeded. “I was worried!”

They shook hands. The colonel, handsome with his strong Nordic face and white-blond hair, smiled and said, “All the ‘salesmen’ checked in. The October ‘customers’ have all been seen; four on the exact dates, two a day early, and one a day late.”

Mengele pressed his chest and breathed. “Praise God! I was worried, the plane coming.”

“I felt like taking a flight,” the colonel said. “It’s such a beautiful day.”

They walked together toward the pathway.

“All seven?”

“All seven. Without a hitch.” The colonel offered the shopping bag. “This is for you. A mystery package from Ostreicher.”

“Oh,” Mengele said, and took it. “Thanks. It’s no mystery. I asked him to get me some silk; one of my housemaids is going to make shirts for me. Will you stay for lunch?”

“I can’t,” the colonel said. “I have a rehearsal for my granddaughter’s wedding at three o’clock. Did you know she’s marrying Ernst Roebling’s grandson? Tomorrow. I’ll have some coffee and talk awhile, though.”

“Wait till you see my chart.”

“Chart?”

“You’ll see.”

The colonel saw, and was enthusiastic. “Beautiful! An absolute work of art! You didn’t do this yourself, did you?”

Putting the shopping bag by the desk, Mengele said happily, “God no, I’m not even sure I can make the checks decently! I had a man flown down from Rio.”

The colonel turned and looked at him, surprised and questioning.

“Don’t worry,” Mengele said, raising a reassuring hand, “he had an accident on his way home.”

“A bad one, I hope,” the colonel said.

“Very.”

Their coffee was brought. The colonel examined some of the Führer’s photos and then they sat on the sofa and sipped at small gold-and-white cups of steaming blackness. “They’ve all settled themselves in apartments,” the colonel said, “except Hessen, who’s bought a camping truck. I told him to call in once a week, since we won’t be able to reach him if we want to. He’s only going to use it till the bad weather sets in.”

Mengele said, “I need to have the dates the men were killed. For my records.”

“Of course.” The colonel put his cup and saucer on the coffee table. “I’ve had it all typed up.” He reached inside his jacket.

Mengele put his cup and saucer down and took the folded sheet of flimsy the colonel offered. He opened it, held it away, squinted at typing. Smiling, he shook his head. “Four out of seven on the exact dates!” he marveled. “Isn’t that something?”

“They’re good men,” the colonel said. “Schwimmer and Mundt have their next ones set up already. Farnbach needed some talking to; he’s a bit of a questioner.”

“I know,” Mengele said. “He gave me trouble when I briefed them.”

“I don’t think he’ll give any more of it,” the colonel said. “I chewed him out good and proper.”

“Good for you.” Mengele refolded the pleasingly crackly paper and put it on the coffee table’s corner, set it flush with the edges. He looked at the chart and imagined the seven red checks he would paint when the colonel left. He lifted his cup, hoping to set an example.

“Colonel Rudel called me yesterday morning,” the colonel said. “He’s on the Costa Brava.”

“Oh?” Mengele saw at once that the pleasure of flying wasn’t the reason the colonel had come. What was? “How is he?” he asked, and sipped his coffee.

Читать дальше

to 94. Ahearn—Kanada—23/4/77

to 94. Ahearn—Kanada—23/4/77