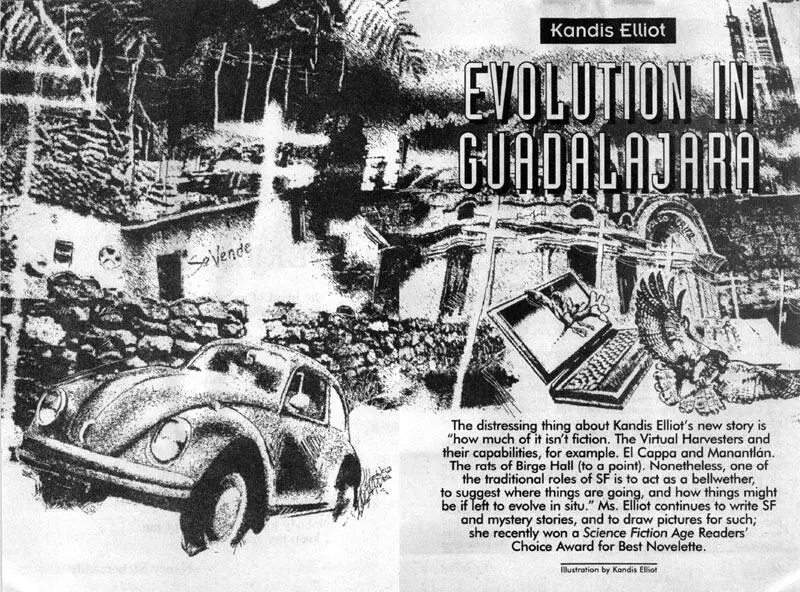

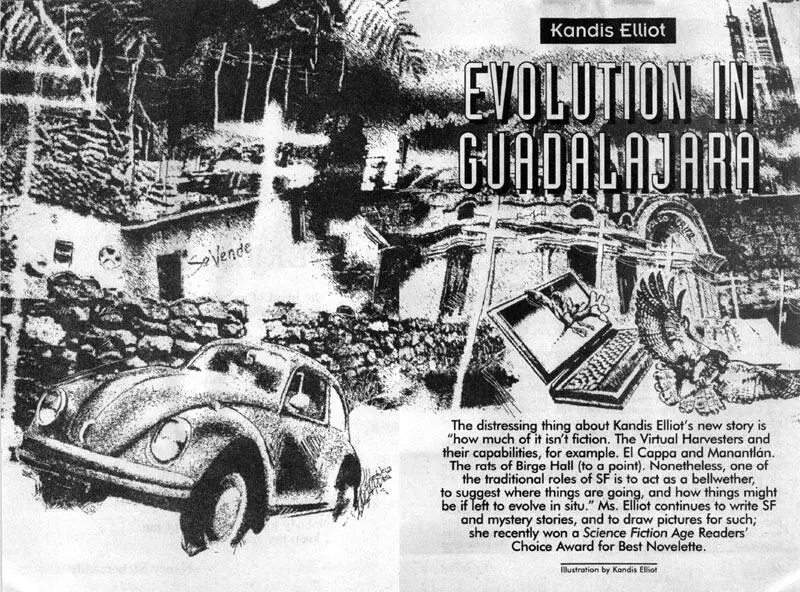

Evolution in Guadalajara

by Kandis Elliot

Illustration by Kandis Elliot

“¡Rapido, Nezzy! Faster!” Ziggy never asked, directed, talked, or orated. He shouted, the man with vocal cords of Polysteel. “If we get there before power poles and wells are sunk, we can ward off development of the hillside, if not the flats. IWT guys can set up a million-dollar bird-watching post out here, maybe even restore some of the native trees—what the hell’s their address? Oh yeah, Inter -national Wilder -ness Too -urs at -dot—” Bang, bang, bang, like a chant his callused fingers pounded out a code on the long-suffering laptop’s grease-corroded keyboard.

Our propane Volkswagen clattered past the outskirts of Guadalajara on roads recently transcended from burro trails by the anointing of lava gravel, palm-sized stones that might as well have been edge-up machete blades, considering the tire slashing they did. The car managed to avoid the most severe lacerating, which was fortunate because Ines, behind the wheel, was looking not at the road but at the steep volcanic flanks rising ahead, and Ziggy was pounding furiously on his laptop, in between wrenching and generally fruitless twists of its comsat transceiver. I was stuck, as usual, in the back seat with The Royal We. I started stroking her fur backward, raising sparks and risking the bloodletting promised by her flattening ears. Transceiver reception cleared.

Ziggy kept up a stream of snarled profanity, his fingers bang-banging out messages and counter-messages as rows of digits danced on the dim little LCD screen. “Projections have over a hundred thousand new constructs up there by Christmas,” he said through his teeth. “That’s economic efficiency in the capitalist marketplace for you. No sewage, no water, no power—”

“Here comes the line now!” Ines held the rearview mirror steady and aimed more or less rearward for a moment. The vibration of the car on the road immediately torqued the mirror cattywompus as soon as she let it go; 99 percent of the time it reflected candy wrappers, ZIP disks, halfeaten tortillas coated with coagulated stuff, and here and there a little patch of gray that was the actual dashboard. Ines poked her head out the window and squinted back through the trail of ochre dust, never mind about steering the car. “jAguas!” she gasped, squinting.

Ziggy, me, even The Royal We were looking by this time, The We lashing her tail and flattening her ears again as though some Mexican dog pack had managed to escape the city taco vendors and were howling on our rear bumper. I could just make out a hazy line of poles about two miles down-slope and gaining on us.

“Step on it, Nezzy,” Ziggy yelled. The instant he had met Inez he’d used the nickname. Inez once told me she thought he simply had a speech impediment, and eventually considered it a brain impediment. She had more trouble with “The Royal We,” which in truth did result in a syntax nightmare—How’s We today? Is We a good kitty? Will The We permit her well-trained human servant to stroke The Royal We’s royal personage? “I’ll give ’em a tourist center—” Ziggy hammered on the laptop’s tight, tiny keys— “that’s a concession. Fifty million new tourist pesos coming in every season alone, two hundred million a year from rich—ah, hell, they’re going to beat us by a country mile.” He’d glanced backward again.

Power lines were popping up along the east side of the road as fast as the eye could follow. Two thick black cables sizzled as they connected the poles, threading the crossbars almost before any materialized. With a whooshing roar the power lines passed us and within moments vanished up the slope and around the mountain road’s next hairpin turn. Scrub trees along the roadside blipped out of existence.

When we reached the plateau, which yesterday had been home to two or three plywood shacks and a half-dozen foundations, we found more than twenty adobe ranch homes, yards enclosed by plastered cinder-block walls, and some forty new foundations. Little blaze-orange flags were blooping up in rectangular formations all over the slopes of the old volcano. The power lines followed them around the crest. Cattle with floppy ears, goodly horns, and dazed expressions wandered among the thorn bushes and excavation mounds of dynamited lava grit. The air was still; few people had moved into their new homes. Water and sewage never kept up with power lines, and around Guadalajara it often never came at all to the flanks of the surrounding peaks.

Inez turned off the VW’s wheezing engine and we all tentatively got out. The Royal We spat at a pushy cow that was a little too brave, protecting a half-grown calf by snorting and pawing twenty yards off. Ziggy’s normally loud voice boomed like cannon fire in the stillness, making the displaced cattle start with alarm.

“Damn- na -tion! Just a day too late. Another couple of projections on tourist dollars and we’d’ve stopped it in its tracks.”

“It might not be too late, Doctor Zygidaynus,” Inez said, pointing to the third house down the rutted, stone-littered construction road. “Somebody already wants out.”

The red adobe-look house was a nice ranch, very Central-Mexico, with an extensive cooking patio and surrounded by a tastefully designed wall that was topped with broken glass inset into the mortar. As we watched, rose bushes jabbed at agave shoots to take over the trampled yard; passion-flower vines twirled like angry rubber bands up the wickerwork patio pillars. A potted palm suddenly cracked the bottom of its pot and sprouted upward three feet, knocking a boat-tailed grackle from his perch on the eaves. Across the red side of the never-tenanted house was painted a whitewashed “Se Vende.”

“Doesn’t matter,” I said. “If the owner can’t sell it right off, the homeless will just move in. Nobody’s going to come up here to chase them away. I doubt if any of these places has a building permit.”

“Of course they don’t,” Ziggy snarled. “People building houses on what they call wasteland isn’t any skin off the law’s ass. Land is to be dominated and populated, Bible says so. And better to siphon off the excess population into the mountains than have it living on the curbs—” he went on for another few minutes, Inez and I knowing better than to interrupt one of his sarcastic tirades about population versus land ethics.

At length we piled in the car and headed back to the central city. Toward the bottom of the mountain we noticed two new polio frito stands, a cervecería, a Pemex station, and four drive-in automated teller islands, each for a different bank, none of which had been there when we started our ascent up the mountain, three hours ago. Inez lifted the mirror and we all watched them occlude behind us as we drove over the lava outbacks and into the thick, egg-yolk haze engulfing Guadalajara.

Our rented lodgings faced Avenida de la Paz, the historic heartline of Guadalajara. The grounds were now guarded by one of the ubiquitous glass-shard-topped walls, but it was once a rich opal miner’s villa. The “mansion” today seemed built for dwarves or munchkins, especially when inhabited by two normal-sized gringos, their liaison, live-in maid, cook, and companion animal; however, its eight rooms and spreading patio were considered extravagant luxury in 1830. As though the city were still tethered to that era, even in the midst of downtown brick, asphalt, traffic, and smog we were awakened each morning in the gray of early dawn by roosters crowing.

This morning I came out to sit by the villa’s palm-shaded pond-cum-swimming pool. About waist-deep and four strokes across, the pool’s tepid water was a beautiful copper-sulfate blue, its central fountain with a pretty sound of spilling water cloaking the growl of the city beyond the wall. As I pulled up a dew-damp lounge chair I noticed that something had just been bathing in the pond. Not a human, at least not a gringo who valued the health of his bodily access orifices; ducks, probably, or pigeons. The wet tiles held a fresh defecation, which I knew would be hosed into the swimming pool as soon as the maid spotted it.

Читать дальше