painter is embarking upon a game of chance in which one false move risks losing everything. In one of Tripp’s earliest paintings, the “ kobaltblaue Krapplackkugel” [cobalt blue madder ball] is already rolling away toward a nocturnal vanishing point on the other side, and in each of the pictures that follow, the most intricate chess moves, circumventions, and evasions are played out back and forth between life and death: ’ tis all a Chequer-board of Nights and Days / Where Destiny with Men for Pieces plays / Hither and thither moves, and mates, and slays / And one by one, back in the Closet lays .

Closely bound up with the theme of death is that of time passing, time past and lost time, which in Jan Peter Tripp’s pictures is suspended — just as in Proust — as ephemeral moments and constellations are preserved from the passage of time. A red glove, a burnt-out match, a pearl onion on a chopping board: these objects contain the whole of time within themselves, as it were redeemed forever by the painstaking, impassioned precision of the artist’s work. The aura of memory which surrounds them lends them the quality of mementos: objects in which melancholy is crystallized. An interior from La Cadière d’Azur shows a whitewashed wall

and the corner of a reproduction in oils, black with age, on which it is just possible to make out the motif of a boating trip across the water. On the wide plaster frame of the print — disguised to look like a mount — is fastened a miniature painted on ivory, a bust in the truest sense of the word, since the face of the subject is so scratched away as to be unrecognizable, and only the head and blue-uniformed shoulders of the unknown hero can be seen. Also attached to the frame is a small bunch of dried flowers (it immediately reminded me of the garland which Karoline von Schlieben wove with Heinrich von Kleist on the Brühlsche Terrasse in Dresden on the sixteenth of May 1801, a photograph of which has survived), as well as a scrap of paper torn from a diary bearing the date of the fifteenth of May — the painter’s birthday.

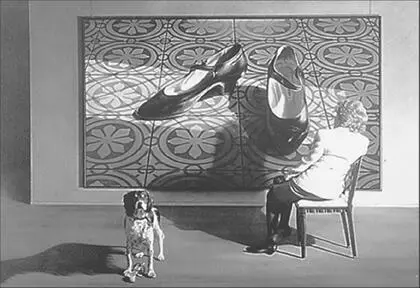

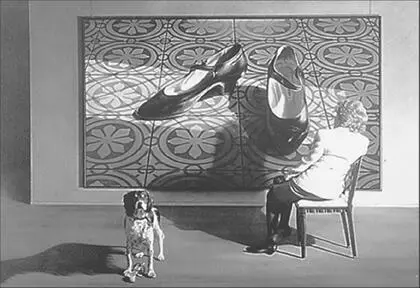

Time lost, the pain of remembering, and the figure of death are here assembled like mementos in a shrine to remembrance, quotations from the painter’s own life. Remembrance, after all, is in the end nothing other than a quotation. And the quotation interpolated into a text or an image forces us, as Eco writes, to revisit what we know of other texts and images, and reconsider our knowledge of the world. That, in turn, requires time. In taking it, we enter upon narrated time and cultural time. Let us attempt, by way of conclusion, to demonstrate this with the painting entitled La Déclaration de guerre , measuring 370 × 220 cm, in which an elegant pair of ladies’ shoes is to be seen upon a tiled floor. The pale blue and off-white pattern on the tiles, the gray lines of the grouting, the diamond pattern cast by the leaded light of the window

across the central portion of the picture, in which the black shoes stand between two areas of shadow; all this taken together produces a geometric pattern of a complexity which is incapable of expression in words. From a combination of this pattern — illustrating the intricacy of the various proportions, relationships, and interlocking connections — and the mysterious pair of black shoes, there arises a kind of picture puzzle that the observer, knowing nothing of the previous history, will scarcely be able to solve. Who was the woman the shoes belonged to? Where has she gone? Do the shoes now belong to someone else? Or are they, in the end, simply a paradigm for the fetish which the painter is compelled to make of everything he paints? It is difficult to say more about this picture than that notwithstanding its imposing scale and deceptive simplicity, it remains locked in the most intimate private sphere. The shoes give nothing away. Two years later, however, the painter brings his enigmatic picture at least a little further into the open. In a work of significantly smaller format (100 × 145 cm), the large picture reappears, not just as a quotation but as a mediating element of the painting. Filling the upper two-thirds of the canvas, it is evidently now hanging in its rightful place, and in front of it, in front of the Déclaration de guerre , perched sideways on a mahogany chair with white upholstery, a woman with flaming red hair sits with her back to the observer. She is smartly dressed but still gives the appearance of someone weary at evening from the burdens of the day. She has removed one of her shoes — the same shoes as the ones she is gazing at in the large picture.

Originally, so I have been told, she was holding this one shoe in her left hand, then it was placed on the floor to the right of the chair, and finally it vanished altogether. The woman wearing one shoe, alone with the mysterious declaration of war — alone, that is, apart from the faithful dog at her side, who, however, is not in the least interested in the painted shoes but gazes straight ahead out of the picture and looks us directly in the eye. An X-ray would show that previously he was standing in the middle of the picture. In the meantime, he has been on a journey and has retrieved a kind of wooden sandal from the fifteenth century, or, as the case may be, from the wedding portrait which hangs in the National Gallery in London, painted by Jan van Eyck in 1434 for Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife in morganatic “left-handed” marriage, Giovanna Cenami, in token of his witness to the union. “Johannes de Eyck hic fuit,” it says on the frame of the circular mirror in which

the scene can be seen again, in miniature, from behind. In the foreground, near the bottom-left-hand edge of the painting, lies the wooden sandal — that strange piece of evidence — next to a small dog who has somehow strayed into the picture, probably as a symbol of marital fidelity. The red-haired woman, who in Jan Peter Tripp’s painting is meditating on the fate of her shoes and an inexplicable loss, has no idea that the revelation of the secret lies behind her — in the form of an analogous object from a world long since past. The dog, bearer of secrets who leaps easily over the dark abysses of time, because for him there is no difference between the

fifteenth and the twentieth centuries, knows many things better than we. His left (domesticated) eye looks straight at us; the right (untamed) eye has just a shade less light, seems remote and strange. And yet, we feel, it is precisely this eye in shadow which can see right through us.

In the “extended marginal notes and glosses”—as he modestly characterizes the essays in A Place in the Country— W. G. Sebald chooses to dispense with the usual scholarly accoutrements of footnotes (with a single exception) and bibliography. In reintroducing such apparatus as an aid for the English reader, I have accordingly tried to keep these notes as unobtrusive as possible, refraining from footnoting the numerous embedded quotations, half-quotations, and allusions. Instead, works cited in the text are, as far as possible, listed and referenced in the Bibliography, where details of the English translations of the authors in question, to which my own translation is indebted, may be found.

Читать дальше