Trompe l’oeil is a manner of painting capable, with relatively limited means — whether by a certain organization of perspective, or an astute deployment of light and shade — of conjuring up the so-called effet du réel as it were from nothing. Its most adept practitioners were, of course, the quadratisti of the baroque era, who traveled all over Austria and Bavaria conferring upon various not particularly impressive intérieurs an illusion of palatial grandeur by painting the walls with whole series of colonnades, and grandiose domes on the ceilings. The whiff of trickery and inconsequentiality, which attaches to any artistic practice whose effects can be indiscriminately deployed, later — at least since the dawn of photography and the beginnings of the modernist era which it ushers in — came to be extended to representational painting as a whole. For this reason, the idea that radically exposed artistic positions might nowadays be arrived at just as readily through representational as nonrepresentational art is, for an art critic, virtually inconceivable; the more so as photo- or hyperrealism, with the tendency to reification implicit in its naturalistic mode of depiction, very rapidly arrived at the limit of its artistic possibilities.

That Tripp’s work is — almost inevitably — discussed in connection with this virtually outmoded movement is, then, the result of a false association. The one thing that seems to me worthy of note is the — implicit — suggestion that the essence of a painting by Jan Peter Tripp lies not in what one might assume to be the purely objective and affirmatory quality of its identical reproduction of reality (or the latter’s photographic image) — that quality which is without fail admired by each and every viewer — but rather in the far more subtle ways in which it deviates and differs from it. The photographic image makes a tautology of reality. When Cartier-Bresson goes to China, writes Susan Sontag, he shows that there are people in China and that these people are Chinese. What may be true of photography, though, is not necessarily applicable to art. The latter depends on ambiguity, polyvalence, resonance, obfuscation, and illumination — in short, the transcending of that which, according to an ineluctable law, has necessarily to be the case. Roland Barthes saw in the — now omnipresent — man with a camera an agent of death, and in photographs something like the relics of life continually giving way to death. Where art differs from such a morbid affair is in the fact that the proximity of life to death is its subject, not its obsession. Art deploys the deconstruction of outward appearances as a means of countering the obliteration, in endless series of reproductions, of the visible world. Accordingly, Jan Peter Tripp’s paintings, too, have a consistently analytic quality rather than a synthesizing one. The photographic raw material which they take as their starting point is painstakingly modified. Artificial distinctions between focus and out-of-focus effects are dissolved, additions and subtractions made. Something may be moved to another place, foreshortened, or rotated a fraction out of kilter. Tonal shades are altered, and from time to time those happy accidents occur which unexpectedly give rise to a system of representation directly opposed to reality. Without such interventions, deviations, and differences, the most perfect re-presentation would be devoid of all thought or feeling. What is more, looking at Tripp’s pictures one would do well to bear in mind Gombrich’s lapidary statement that even the most meticulous realist can accommodate only a limited number of marks in the allotted space. “And though he may try,” writes Gombrich, “to smooth out the transition between his dabs of paint beyond the threshold of visibility, in the end he will always have to rely on suggestion when it comes to representing the infinitely small. While standing in front of a painting by Jan van Eyck we … believe he succeeded in rendering the inexhaustible wealth of detail that belongs to the visible world. We have the impression that he painted every stitch of the golden damask, every hair of the angels, every fiber of the wood. Yet he clearly could not have done that, however patiently he worked with a magnifying glass.” In other words, the creation of a perfect illusion depends not only upon a vertiginous degree of technical ability, but ultimately upon the intuitive channeling of a breathless state in which the painter himself no longer knows whether his eye still sees or his hand still moves.

The recurring experience of a state of utmost concentration in which the breath grows ever shallower, the silence ever greater, the limbs gradually grow numb and the eyes grow dim, brought death into the paintings of Jan Peter Tripp. Unmistakably present in the early studies of bones and skulls, in later works it tends to lie concealed within the ominous-looking objects, in the faces of those portrayed, in the crack in the glass, the hermetic form of the pebbles, or the portrait of Kafka at fifty. In order to discover it, the painter had to venture across the border. On the way to the other side, too, was the dormouse discovered one morning lying on the doorstep. Although it is said that one should paint the dead quickly, surrounded by the chloroform stench of decomposition Tripp took seven days over the picture in which the silent message of this unexpected guest is preserved.

On the seventh day, there was one final tiny movement in the long since lifeless body, and a drop of blood the size of a pinhead appeared at the nostril. That was the true end. Nestling in nothingness, with neither ground nor background, the creature hovers now, its bat ears extended, through thin air. The black patch of fur around its eyes is reminiscent of a mourning band, or an eye mask worn by a sleeping passenger on a summer night’s flight over the North Pole. We are such stuff / as dreams are made on; and our little life / is rounded with a sleep .

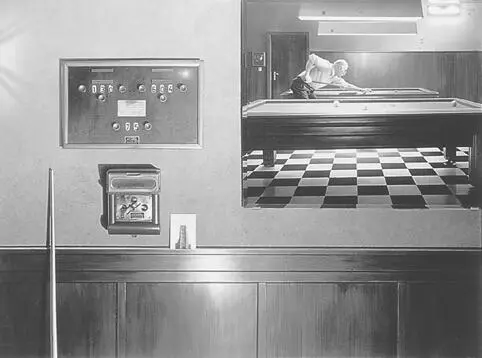

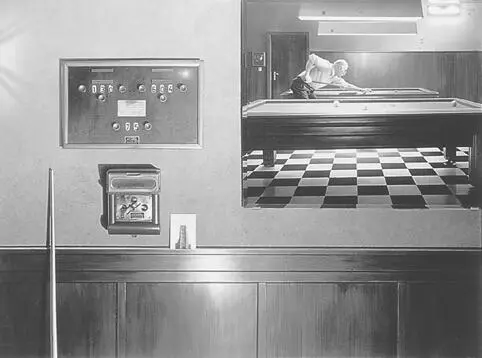

The longer I look at the paintings of Jan Peter Tripp, the more I realize that beneath the surface illusionism there lurks a terrifying abyss. It is, so to speak, the metaphysical underside of reality, its dark inner lining. This hidden lining is revealed in a series of flower paintings, only recently begun, which despite their high degree of realism leave botanical illustration far behind. The flowers, which originally were to have been painted in the full glory of their natural colors, have become silent grisailles in which only the ghostliest trace of color remains. They are as if disembodied, trapped in the porcelain stillness of death. All of them bear women’s names and as such are of another kind. Yet their flamboyant, divalike forms still retain a pale reflection, faded almost to nothing, of organic living nature. In the painting of the green grapes, too, these latter represent one last sign of life. A strangely ceremonial, emblematic style governs the composition. The dark background, the white linen cloth with the embroidered monogram — already we begin to sense that it is spread out not for a wedding breakfast, but on a bier or catafalque. And what is the business of painting in any case but a kind of pathological investigation in the face of the blackness of death and the white light of eternity? This extreme contrast of light and dark recurs on a number of occasions, for example in the checkerboard pattern of the floor tiles in the Belgian billiard picture from Tongres, which not coincidentally seems to suggest that in any given frame the

Читать дальше