made of “yards and yards of yellow silk … and an additional tiny balloon … provided for the sole use of the fortunate Midget. At the immense altitude,” writes Nabokov, “to which the ship reached, the aeronauts huddled together for warmth while the lost little soloist, still the object of my intense envy notwithstanding his plight, drifted into an abyss of frost and stars — alone.”

AS DAY AND NIGHT — On the paintings of Jan Peter Tripp

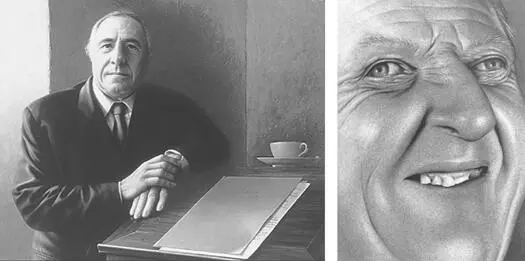

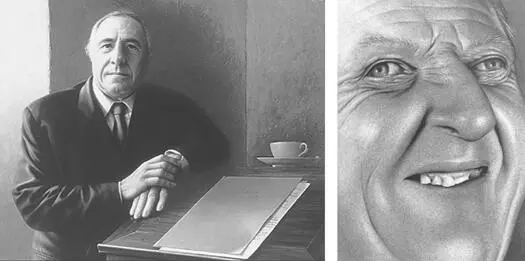

The catalog of Jan Peter Tripp’s oeuvre today goes back more than a quarter of a century. It comprises works on a range of vastly differing scales, executed in pencil, charcoal, and drypoint, in watercolor, gouache, and grisaille, acrylics and oil, taken to the furthest limit of the possible and frequently, or so it appears to the observer, some way beyond it. The pictures from the first three or four years of Tripp’s career still clearly show the influence of surrealism, of the Vienna school of fantastic realists, and of photorealism, still embedded in the polemical strategies of 1968; but soon afterward, during the months spent as an artist in the regional psychiatric hospital at Weissenau near Ravensburg in 1973, this polemical trait disappears, to be replaced by a far more radical objectivity which, by simply representing life in all its manifestations, seeks to establish what gives rise to its particular evolution and expression. In this way, the art of portraiture becomes an exercise in pathography, no longer admitting of any distinction between what is generally known as the character of the individual and the deformations occasioned by the ordeals of work and mental suffering in the subject portrayed. If the paintings of the Weissenau asylum inmates may be understood as studies of the echoing void in the heads of humankind, then this is no less true of the late portraits and self-portraits, with their almost otherworldly sense of isolation. Even the most recent portraits of respected incumbents of positions of economic and political power have (without the slightest defamatory intention) a tortured self-consciousness and a slight air of derangement about

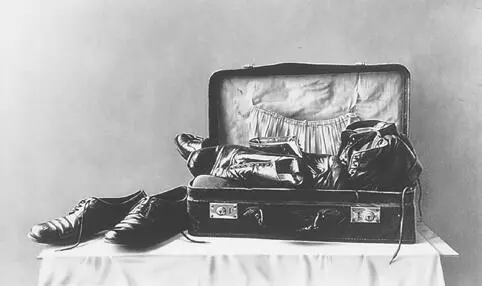

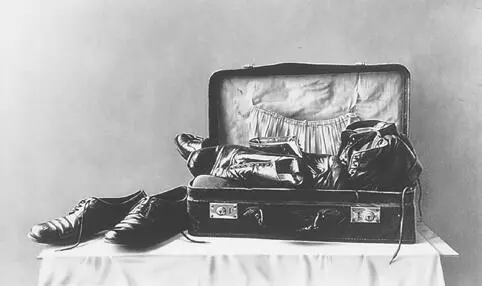

them, and so share a secret affinity with the definition, arrived at in Weissenau, of the human individual as an aberrant creature, forcibly removed from its natural and social environment. The obverse of this depiction, of a race growing ever more monstrous in the so-called process of civilization, are the deserted landscapes, devoid of all human presence, and in particular the still lifes, in which, far removed from the world of events, only the motionless objects are left to bear witness to the former presence of a strangely rationalistic species. Tripp’s still lifes are not primarily concerned with the skill and mastery of the artist, exercised upon a more or less random assemblage , but rather with the autonomous life of things — in relation to which we, as creatures in blind thrall to the world of work, find ourselves in a subordinate and dependent position. Since (in theory) things outlast us, they know more about us than we do about them; they bear their experience of us within them and are —in a literal sense — the book of our history lying open before us. In the father’s so-called Russian suitcase lie the shoes of the son;

two dozen slates and a few faded scribblings evoke an entire vanished class of schoolchildren — images of the past, of the most mysterious aspects of a life. In Tripp’s work, more clearly than ever before, the nature morte represents the paradigmatic expression of what we leave behind. Looking at it, we become aware of what Maurice Merleau-Ponty, in L’Oeil et l’Esprit , has called “le regard préhumain,” for in such painting the role of the observer and the observed object are reversed. In gazing, the painter surrenders our all-too-superficial knowledge; things look across at us, unblinking, and fix us in their gaze. “Action et passion si peu discernables,” writes Merleau-Ponty, “qu’on ne sait plus qui voit et qui est vu, qui peint et qui est peint.”

Thinking about the work of Jan Peter Tripp, and the way in which, in it, the exact reproduction of reality achieves an almost unimaginable degree of precision, it is impossible to avoid the tiresome question of realism. On the one hand, because the first thing to strike anyone looking at a picture by Tripp is the apparently flawless accuracy of representation, and on the other, because, paradoxically, it is precisely this astounding facility which distorts the view of its true achievement. The perfect surface of the completed picture offers so little in the way of clues that even professional art criticism has scarcely anything meaningful to add to the lay utterances of astonished admiration. Such utterances are, moreover, typically made with (so to speak) an incredulous shake of the head, since the unquestioning admiration is in all likelihood tempered — particularly in the case of those critics schooled in the traditions of modernism, who tend on the whole to be largely ignorant when it comes to matters of technique — with the uneasy sensation of having been taken in by some kind of illusionist or confidence trickster operating with all manner of inscrutable sleights of hand. Indeed, not only does Tripp succeed in interpolating the third dimension into the surface of the painting, to the extent that, looking at it, one sometimes has the feeling one could step over the threshold and enter the picture itself; but the materials represented, too, the cypress black of young Marcel’s velveteen jacket, his

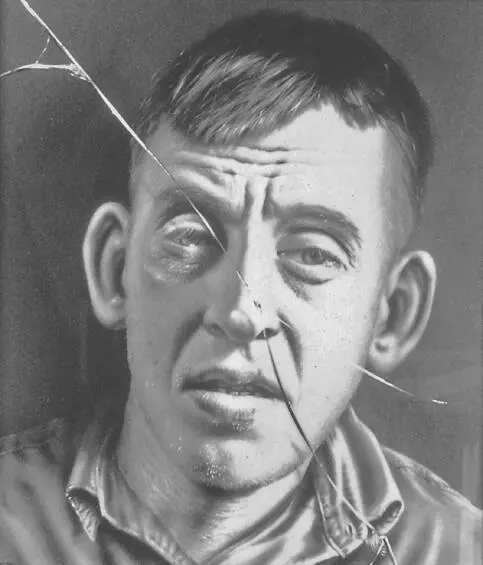

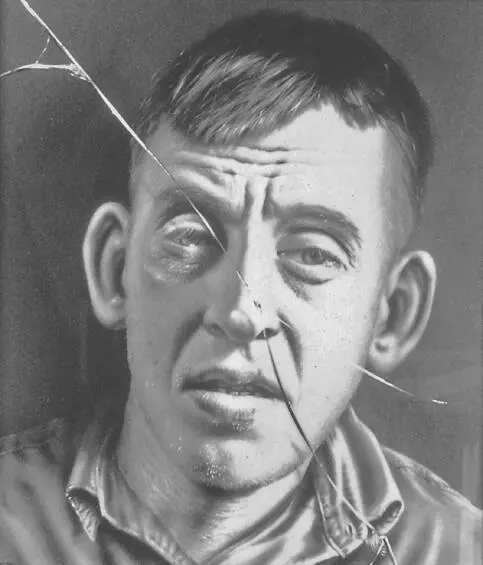

taffeta bow, the forty-one pebbles, and the white snow on the field, appear so truly real in the painting that one involuntarily reaches out a hand to touch it. Ernst Gombrich, in his comprehensive work on art and illusion, recalls the story Pliny relates of the two Greek painters Parrhasius and Zeuxis. Zeuxis, it is said, painted grapes in such a deceptively realistic manner that the birds tried to peck at them. Parrhasius then invited Zeuxis to his studio in order to show him his own work. When Zeuxis went to draw back the curtain in front of the picture to which Parrhasius led him, he discovered that it was not in fact real, but only painted. Gombrich goes on to explain how, in trompe l’oeil painting, the suggestive power of the picture and the expectation on the part of the viewer mutually reinforce each other, and he concludes the section with the remark that the most convincing trompe l’oeil he had ever seen “simulated” a broken pane of glass in front of the picture.

Well, in Tripp’s work we find both the grapes of Zeuxis and the broken pane of glass. And yet it would be wrong to regard him first and foremost as a virtuoso of trompe l’oeil painting. Tripp makes use of trompe l’oeil as just one technique among many, and always — as the watercolor Ein leiser Sprung [ A Little Crack(ed) ] illustrates — with the closest possible link to the subject of the painting.

Читать дальше