Late in February 1947 I left Sehjodnya and returned to Moscow. Here I was put through an intensive interrogation by the Political Department of the Centre in a last final check-up of my political reliability. All was apparently well, and I passed this, my final examination at the hands of the Russians, with flying colours.

There was one final banquet for me at which the director, Victor, and the chief political instructor of the Centre were present, and then one morning early in March I left Moscow for the airport and Berlin. I was travelling this time as Major Granatoff and was accompanied by a courier whose job was to steer me through the controls and customs in Moscow and Berlin and to ensure that all was done with the minimum of publicity.

As I flew over the endless, dreary wastes of Russia, at last travelling westward for the first time for over two years, I comforted myself with the thought that I had at least left the frying pan and was within measurable distance of being out of the fire. Unless unforeseen circumstances prevented it, or I bungled things at the last moment, there now seemed every chance that shortly I should be able to cut myself loose from the Centre forever.

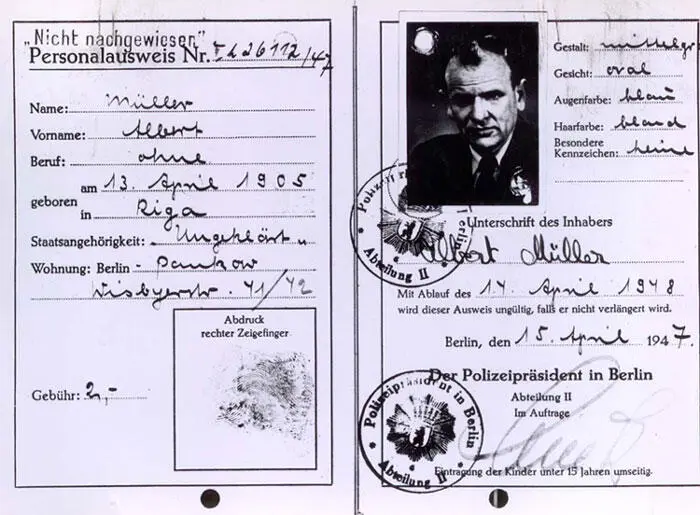

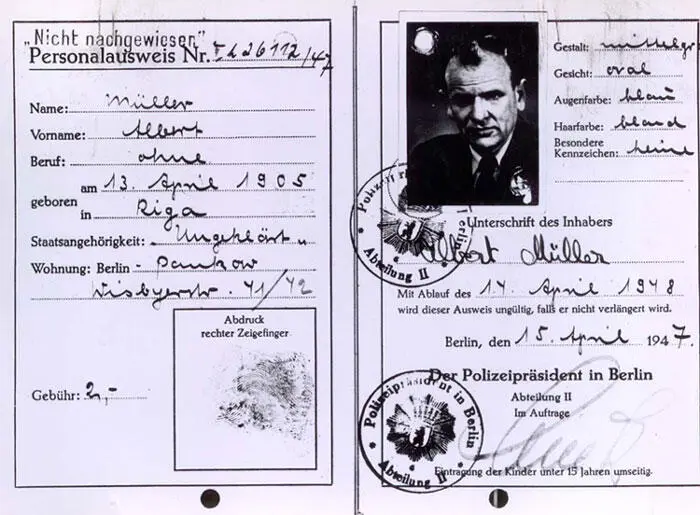

A copy of Foote's false German passport with a photograph

It seemed reasonable to hope, after all the discussions and delays in Moscow regarding my assignment abroad, that when I finally arrived in Berlin something might have been done to enable me to take up my new role at once. Such hope was, however, in vain. The inefficiency of the Russian Intelligence Service in matters of detail and administration was a perpetual source of amazement to me. It would seem impossible to an ordinary person that a service run on such inefficient lines could ever achieve any results. Any ordinary intelligence service would have fiddled itself into inanition long ago. That the Red Army Intelligence continues to function and to function efficiently is due, I feel, far more to the efficiency of its agents and organisers in the field and to the facilities offered by the local Communist parties than to the driving and organising power of the Centre.

I was met at the Berlin airport by a Captain Smirnov, the Berlin representative of the Centre, who stated that though he had received instructions that I was to adopt the role of Albert Mueller at once he frankly had not the first idea of how to set about it. The Centre had stipulated, for obvious security reasons, that there must be no trace of Soviet help in obtaining my documentation, as this might be checked up by a future German government. Poor Smirnov did not know even how to begin on such a task. As a result I was given a flat at Grellen - strasse 12, in the Soviet Zone of Berlin, and lived there in my role as Major Granatoff.

After a series of talks with Smirnov, who could not have been pleasanter and could not possibly have had less idea how to set about things, it was obvious that if ever I was to get papers at all I would have to set about doing it myself. I therefore started off on the long and wearisome process of getting myself documented with no assistance, official or unofficial. For anyone trying to do the same thing in Berlin I can give the only two infallible ingredients for success: endless patience and an inexhaustible supply of cigarettes. With these two assets anything can be done in Berlin - in time.

My only documentary asset was a certificate of release as a prisoner of war which Smirnov did manage to supply. Each morning I started off on my tour of the municipal offices in the Soviet Zone and by the time I had achieved my object I had interviewed most of the officials in the burgermeister's office, the Housing Office, the Labour Exchange, the Food Office, the Health Office, and of course the police. I had to get documents not only to prove that I was Albert Mueller but also to allow me to live in Berlin. The former was a great deal easier than the latter as Berlin was grossly overcrowded and many genuine Berliners who had been evacuated during the war were clamouring to come back, and they obviously had far more right to live there than did Mueller, a former resident of Riga. By design both Riga and my later notional domicile, Koenigsberg, were in Russian hands, and the archives of the Wehrmacht, which would have shown a significant absence of any mention of Albert Mueller late of a transport command, were also in the hands of the Allies and not available to the German authorities.

Almost all the officials were new to their jobs, being former members of the Communist Party and former inmates of concentration camps. The procedure was for each official after hearing my story to pass me on to another official, a little higher up in the hierarchy, to whom I told the same rigmarole again. No one seemed to know quite what to do with a case like mine and I was indeed somewhat of a curiosity, as not many prisoners had then been returned to Germany from Russian camps. Each interview and each request for an interview was accompanied with a suitable douceur in the form of cigarettes.

I was invariably asked about my life as a prisoner of war and I always pitched a good, full-blooded horror story. All the officials were allegedly members of the S.E.D., the Communist-dominated German Unity Party, but the story was always very well received by these outward collaborators with the Russians. I was reminded of the old prewar anti-Nazi joke about a "Berlin steak" which was "brown outside and red inside." The roles were partially reversed. Soviet Berlin was a beautiful uniform red outside. The colour of the steak inside varied, but it was very seldom red all through.

Patience and cigarettes won through in the end and on April 12, 1947, I received my documents and was allocated a room in a flat belonging to Frau Weber, Wisbyer - strasse 41, Pankow. Up to this time I had been living the life of the destitute and homeless Mueller during the day, and at night returned to the sybaritic existence of Major Granatoff. The time had now come to discard Major Hyde and become permanently Herr Jekyll. Before doing so, however, I transferred to my new room all the food I had managed to bring with me from Russia or amass during my stay at Grellenstrasse. I had also been given thirty thousand marks as salary for a year but this was of little use as compared to my stock of food and cigarettes. I was determined before I finally left Russian service to have a short, final fling and had collected this food in order to have a holiday of a month or two.

Before I ceased to be Major Granatoff, part time, a place of conspiracy in Berlin had been arranged by Smirnov. In case the Centre wished to contact me I was to go on the last Sunday in every month to the Prenzlauer station, carrying a leather belt in one hand and my hat in the other. If the Centre wished to contact me someone would come up to me and say, " Wann fahrt der letzte Zug ab? [When does the last train go?]" My reply was: "Seit Morgen urn 22 Uhr [Since tomorrow at 10 p.m.]." If on the other hand I wanted to contact the Centre all I had to do was put a notice on a certain public notice board in Berlin reading: "Suche Kinderfahrrad. A. Kleber Muristrasse 12, Berlin/Gruenau [Wanted, a child's bicycle]," and the next day an agent of the Centre's would come to the place of conspiracy at the Prenzlauer station. He would come straight up and say that he had seen the advertisement, for I would be known to him by sight as a result of my monthly visits. I went to the rendezvous once or twice and succeeded in identifying the Centre's agent but he never contacted me and I never tried to get in touch with him. For all I know he is still faithfully turning up there once a month.

Читать дальше