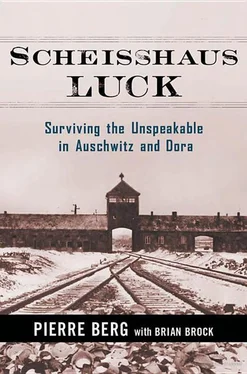

For purely utilitarian reasons, I.G. managers alleviated some of the worst working conditions. In order to curtail the ten-kilometer daily march, a short railway line was built between the camp and the building site. To place some distance between sadistic SS guards and the prisoners, the building site was enclosed with a fence while the guards remained along the periphery outside the plant. The latter project took much longer to complete than anticipated because the Auschwitz-based SS Company, German Equipment Works ( Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke ), was unable to deliver the fence in timely fashion. Shortly after the fence was erected, and only weeks after the first Jewish prisoners started to work on the job site, typhus and typhoid epidemics broke out in Auschwitz concentration camp. In late July 1942, Höss responded by quarantining the camps and murdering the infected. The epidemics were directly attributable to the SS and I.G. because prisoners were forced to endure inhuman conditions with vicious treatment, starvation diet, exhaustive labor, and unrelieved stress. In coping with the temporary loss of unskilled camp labor, I.G. allocated a fourth work camp, intended originally for civilian workers, to serve as a new Auschwitz satellite, Monowitz. {20} 20 20. As summarized in White, “Primacy,” chap. III.

Erected on the building site’s periphery in what had been the demolished Polish village of Monowice, the new camp opened in late October 1942. From beginning to end, Monowitz’s population was overwhelmingly Jewish. The camp prominents included German criminals and a small number of German Jewish political prisoners removed from camps in the Old Reich. The latter prisoners were transferred on Himmler’s order to make “ Judenfrei ” (free of Jews) the older concentration camps like Dachau and Buchenwald.

Consisting mostly of Communist Party members, these Jewish prisoners formed the nucleus of the resistance and their actions made Monowitz far less deadly for the prisoners than it otherwise would have been. {21} 21 21. NARA, RG-242 (Captured German Documents), Nuremberg Organizations (NO-) 1501, Gerhard Maurer, SS-WVHA Office DII Rundschreiben, Abschrift, DII/1 23 Ma/Hag., 5 Oct. 1942.

Nevertheless conditions were lethal at Monowitz. Between November 1942 and January 1945, the death toll reached between 23,000 and 25,000 prisoners. This estimate excludes the losses of early Auschwitz prisoners in 1941 and 1942—that is, before Monowitz’s establishment. At Monowitz, the SS undertook periodic “selections” of weakened prisoners, known as Muselmänner , during camp marches. I.G. managers attended some of these selections.

The SS dispatched the selected to Birkenau for gassing or to Auschwitz for killing by lethal injection. On a smaller scale the selections continued in the infirmary, where SS doctors ordered the transfer for killing of those prisoners whose recovery would occupy bedding space for an indefinite period. Because Monowitz was built partly in response to Auschwitz epidemics, the firm took steps to ensure that new detainees had not been exposed to typhus. These measures were not always benign. After selection at Birkenau, new prisoners were taken to Monowitz and held in a quarantine camp for several weeks. While there they worked as a segregated labor detail at the construction site. The manifestation of typhus symptoms among any new arrivals led to the murder of the entire detachment. {22} 22 22. On the infirmary’s genocidal role, White, “Primacy,” chap. IV and pp. 328–342.

By the time Mr. Berg arrived at Monowitz, the I.G. building site had assumed recognizable shape as a chemical plant, in spite of war-economy frictions and SS incompetence. In the fall of 1943, the plant began producing synthetic methanol, an alcohol derived from coal under immense pressure. Methanol was useful in the production of rocket fuel and explosives and constituted I.G. Auschwitz’s principal contribution to the German war economy. The plant also produced the explosives component, diglycol, and in the summer of 1944 was contracted to produce phosgene, a chemical weapon used in combat during World War I, but not World War II. {23} 23 23. United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Oil Division, Powder, Explosives, Special Rockets and Jet Propellants, War Gases and Smoke Acid (Ministerial Report No. 1), 2nd ed. (NP: Oil Division, Jan. 1947), pp. 3–4, 22, 54, Exhibit H.

With increasing need for skilled laborers to outfit the partially finished buildings, many unskilled prisoners were redeployed from the autumn of 1943 in the construction of makeshift and permanent air-raid shelters. Previously, the firm had given air-raid protection low priority, but abruptly changed course with the Allied advances in Sicily and Italy in the summer of 1943. (The capture of southern Italy brought Poland within the theoretical bombing range of the U.S. Army Air Force.) The air campaign in the summer and fall of 1944 magnified the horrors of the prisoners’ daily existence, even as these attacks underscored that the Nazi regime’s days were numbered. At least 158 Monowitz prisoners were killed in the course of four U.S. daylight bombing raids between August and December 1944. The Soviets also attacked the plant at least twice in December 1944 and January 1945. The number of detainees killed in the December and January attacks is unknown, but all the air attacks disrupted water, food, and electrical power, even as they also raised morale. {24} 24 24. White, “Target Auschwitz,” p. 72 n. 23.

By December 1944, the I.G. Auschwitz labor force included almost every European nationality. Its “paper” strength was 31,000, with 29,000 effectives at work. These workers included Italian civilians and Italian military internees, British POWs, Belgian and French contract workers, numerous Poles and Ukrainians (both forced and “free”), and other non-Jewish Eastern Europeans. The status of workers, free or forced, depended upon the regime’s dictates and I.G. Farben’s assessment of their labor productivity. Theoretically, Monowitz comprised one-third of the total I.G. Auschwitz workforce (just over 10,000 prisoners), but the number of forced laborers at the plant was smaller. In November 1944 the WVHA listed Monowitz as a new main camp, with responsibility for the almost forty Auschwitz satellites. The establishment of the Monowitz and Mittelbau (Dora) main camps was part of the last reorganization of the SS camp system. {25} 25 25. On the IG Auschwitz workforce, see NARA, RG 238, microfilm publication M-892, USA v. Carl Krauch, et al. (IG Farben Case), roll 65, frame 813, Walther Dürrfeld Exhibit 136, Document 1505, Five Personnel Charts for IG Auschwitz, 1941–1944.

For Monowitz’s prisoners, horrible days lay ahead. In January 1945, the Soviets began the Vistula-Oder Offensive and the timing caught the German army by surprise. The Red Army consequently captured the still unfinished plant with little damage. The SS evacuated Monowitz on 18 January, as part of the larger evacuation of the Auschwitz satellite camps. The “death march” that Mr. Berg describes so vividly had begun. {26} 26 26. Christopher Duffy, Red Storm on the Reich: The Soviet March on Germany, 1945 (New York: Atheneum, 1991); on IG Auschwitz’s last days, White, “Primacy,” pp. 310–314.

After four years of construction, I.G. Auschwitz remained unfinished. Under the Germans at least, it never produced synthetic oil or rubber, but wasted tens of thousands of human lives. The plant was a monument to a totalitarian dictatorship that enlisted private industry in the service of refashioning humanity along “racial” lines.

Читать дальше