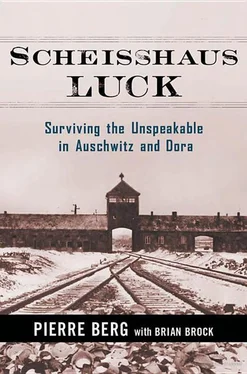

The following comments are intended to set Mr. Berg’s memoirs in the context of the Nazi concentration camp system and the I.G. Farben project at Auschwitz.

♦ ♦ ♦

When Pierre Berg entered Auschwitz-Monowitz in January 1944, the Nazi concentration camps had been operational for almost eleven years. The history of the concentration camps can be divided into six phases, each tied to the Nazi regime’s changing political or military fortunes. Mr. Berg entered the camps during their fifth phase (1942–1944). In the first (1933–1934), the concentration and “protective custody” ( Schutzhaft ) camps contributed to the Nazi Seizure of Power, and to the subsequent “synchronization” ( Gleichschaltung ) of German society. The Nazi Schutzstaffel (SS or Protective Corps) established one of the first concentration camps at Dachau in March 1933 and the Storm Troopers ( Sturmabteilungen , or SA) created ad hoc camps in many localities. After 1933 the total camp population declined drastically because of amnesties. It consisted mainly of political prisoners, especially communists and socialists. Career criminals newly released from prison also appeared in the early camps. During the first phase, Dachau became the model camp when its second commandant, Theodor Eicke, established severe regulations for the permanent SS camps. In July 1934, Eicke became the first Inspector of Concentration Camps (IKL), after playing a key role in the purge of leading SA members during the “Night of the Long Knives.” The IKL’s establishment ushered in the camps’ second phase, 1934 to 1936, when most remaining early camps were closed and Eicke practiced what historian Michael Thad Allen terms “the primacy of policing”: camp labor was supposed to be torture that served no rational end. {11} 11 11. For the six-phase schema, see Karin Orth, Das System der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager: Eine politische Organisati-onsgeschichte (Hamburg: Hamburger Edition, 1999); an older, three-phase scheme is outlined in Falk Pingel, Häftlinge unter SS-Herrschaft: Widerstand, Selbstbehauptung, und Vernichtung im Konzentrationslager (Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe, 1978), p. 14; and idem, “Resistance and Resignation in Nazi Concentration Camps,” in The Policies of Genocide: Jews and Soviet Prisoners of War in Nazi Germany , ed. Gerhard Hirschfeld (London: Allen & Unwin, 1986), pp. 30–72. Klaus Drobisch and Günther Wieland, System der NS-Konzentrationslager, 1933–1939 (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1993), 11–75; see also Wolfgang Benz and Barbara Distel (eds.), Instru-mentarium der Macht: Frühe Konzentrationslager, 1933–1937 (Berlin: Metropol, 2003); Charles W. Sydnor, Jr., Soldiers of Destruction: The SS Death’s Head Division, 1933–1945 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977), pp. 15–17; quotation in Michael Thad Allen, The Business of Genocide: The SS, Slave Labor, and the Concentration Camps (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), p. 36.

The third phase of Nazi concentration camps took place from 1936 to 1939. This period saw first the limited and then mass expansion of the camps, with the establishment of Sachsenhausen (1936), near the site of the former early camp of Oranienburg, Buchenwald (1937), Mauthausen (1938), Flossenbürg (1938), and finally Ravensbrück women’s camp (1939). The last early camps, including Esterwegen and Sachsenburg, closed at this time. “Asocials,” who allegedly avoided work, engaged in prostitution, or whose behavior otherwise fell short of the ideal “national comrade,” were targeted for mass arrest in 1937. Also in 1937, the camp authorities established a standardized triangle system for the entire camp system, which indicated the reason for arrest on the prisoner’s striped uniform. As described by Buchenwalder and sociologist Eugen Kogon, this system fueled bitter prisoner rivalries and thus served the SS objective of divide et impera . A red triangle symbolized political detainees; green, career criminals; purple, Jehovah’s Witnesses; black, “asocials”; blue, Jewish emigrants; and pink, homosexuals. Jewish detainees were identified by combining a yellow triangle with an above-listed arrest category in the form of a Star of David. The first mass influx of Jews into the camps occurred in the second phase, with the temporary arrests of tens of thousands of Jewish men following the November 1938 pogrom, misleadingly known as “The Night of Broken Glass” ( Kristallnacht ). {12} 12 12. Falk Pingel, “Concentration Camps,” s.v., Encyclopedia of the Holocaust , ed. Israel Gutman (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co.; London: Collier MacMillan, 1990); Eugon Kogon, The Theory and Practice of Hell , trans. Heinz Norden (New York: Berkley Books, 1980 [1950]), pp. 29–39; on the triangle system’s origins, see An-nette Eberle, “Häftlingskategorien und Kennzeichnungen,” in Wolfgang Benz and Barbara Distel (ed.), Der Ort des Terrors: Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager , vol. I: Die Organisation des Terrors (Munich: C.H. Beck, 2005), pp. 91–109.

During the fourth phase, 1939 to 1941, the SS extended the camp system and the accompanying terror to the conquered territories. The new camps included Auschwitz (1940), Neuengamme (1940), Gross Rosen (inside Germany, 1941), and Natzweiler (1941). With Eicke’s appointment to command the SS Death’s Head Division ( Totenkopfsdivision ) in wartime, SS-Brigadeführer Richard Glücks became the new Inspector. An ineffectual, colorless individual, Glücks did little to stamp an imprint upon IKL. With war’s outbreak, the Gestapo immediately dispatched political opponents to the camps, like Sachsenhausen, for execution, without a judicial sentence. At this time, tensions began to surface between administrators who saw the camps as intended exclusively for breaking the regime’s enemies and those who desired to exploit captive labor for the economy. In this period, Eicke’s protégeś held the upper hand: SS overseers employed what was euphemistically termed “sport” for the purpose of killing or demoralizing prisoners, including purposeless labor conducted at breakneck pace as a form of torture. In the mid-1930s, at a time of high unemployment, Reichsführer-SS Himmler led German industrialists on a tour of Dachau, with the aim of both justifying the necessity of unlimited detention and eliciting interest in his captive labor supply. Only the civilian worker shortages produced by Nazi rearmament (1936–1939) altered the situation, however, when the SS created an enterprise to prepare building stone for Adolf Hitler’s numerous monumental projects and then developed other businesses connected to the its far-flung missions. As Allen convincingly shows, the SS were disastrous managers, which when combined with “sport” meant that these new enterprises foundered. {13} 13 13. Allen, The Business of Genocide , chaps. 1–2; Reinhard Vogel-sang, Der Freundeskreis Himmler (Göttingen, Zürich, and Frankfurt: Musterschmidt, 1972), pp. 88–89.

Among the fourth-phase camps, Auschwitz was originally intended to hold Polish political enemies. Founded in June 1940, over a thousand Poles were detained there less than six months later.

The first Auschwitz commandant, Rudolf Höss, transferred a small number of hardened German criminals from his previous assignment at Sachsenhausen to serve as camp trusties. An “Eicke School” commandant, Höss oversaw Auschwitz’s transformation from political prison to industrial complex and, most infamously, killing center. {14} 14 14. Rudolf Höss, Commandant of Auschwitz: The Autobiography of Rudolf Hoess , introduction by Lord Russell of Liverpool, trans. Constantine FitzGibbon (Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Co., 1959), passim .

Читать дальше