Installed at one building in each quadrant, these baskets were intended to reinforce the alarm system. This small detail does not overshadow the import of Mr. Berg’s testimony—namely, that prisoners scattered helter-skelter around the plant because they were denied access to air-raid shelters. Their concern was more than theoretical, because U.S. and Soviet forces bombed I.G. Auschwitz six times between August 1944 and January 1945. {5} 5 5. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives, Moscow Central State Osobyi (special) Archives, Record Group (RG-) 11.001 M.03, Zentralbauleitung der Waffen SS und Polizei Auschwitz, fond (record group) 502, opis (inventory) 5, delo (file) 2, roll 70, Rundschreiben Nr. 8013/44, IG Auschwitz Werksluftschutzlei-tung, Dürrfeld, Betr.: “Sichtbares Warnsignal,” 25 Aug. 1944, p. 43; on the documented air attacks, see Joseph Robert White, “Target Auschwitz: Historical and Hypothetical Allied Responses to Allied Attack,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies ( HGS ) 16:1 (Spring 2002): 58–59.

Like Levi and Paul Steinberg, the real-life “Henri” of Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz , Mr. Berg met British POWs at I.G. Auschwitz. The POWs were held at a subcamp E715 of Stalag VIII B (Lamsdorf/Teschen). E715’s population rose to approximately 1,200 by December 1943, but declined to 600 in Spring of 1944, when about half were transferred elsewhere. Mr. Berg’s description of the POWs as healthy “strutting roosters” dovetails with accounts by Levi and Steinberg. The British were proud of their strong military bearing, in contrast to the shabby Wehrmacht guards who con-trolled them. As Mr. Berg recalled, the POWs quickly caught the attention of female civilian workers, most notably Poles and Ukrainians. Although Mr. Berg characterized the POWs as “Commonwealth,” they were mostly English with a small number of Canadians, Australians, and South Africans included. Realizing their special status among the plant’s forced laborers, particularly their protection under the Geneva Convention, and gathering significant details about the Nazis’ murderous activities, the British did what they could to aid the far more numerous “stripees” in their midst. {6} 6 6. Steinberg, Speak You Also ; White, “’Even in Auschwitz… Humanity Could Prevail’: British POWs and Jewish Concentration-Camp Inmates at IG Auschwitz, 1943–1945,” HGS 15:2 (Fall 2001): 266–295.

With respect to Dora, Mr. Berg’s account complements Yves Beón’s Planet Dora . As Michael Neufeld observes, French memoirs have dominated the testimonies of this camp, despite the fact that the French were listed as the third most numerous nationality, behind the Soviets and Poles, in a 1 November 1944 SS report. What sets Mr. Berg’s testimony apart is the timing of his arrival, during the winter of 1945, almost one year after the completion of the barracks and more than six months after the underground factory achieved full operational capacity. The barracks relieved the early prisoners, like Beón, of sleeping inside the tunnel. While many French prisoners were transferred to Dora after brief confinement in Buchenwald, Mr. Berg’s Monowitz experience sets “Planet Dora” in a different perspective, as he arrived after the production passed its peak but before the evacuations began. Unlike many French prisoners, Mr. Berg had already experienced the shock of entering a concentration camp, after surviving one year at Auschwitz and a terrifying evacuation. {7} 7 7. For the nationality figures, see Michael Neufeld, “Introduction: Mittelbau-Dora—Secret Weapons and Slave Labor,” in Beón, Planet Dora , p. xx; idem, “Foreword,” in Sellier, A History of the Dora Camp , p. x; for the history of Dora, see also Joachim Neander, Das Konzentrationslager Mittelbau in der Endphase der NS-Diktatur: Zur Geschichte des letzten im “Dritten Reich” gegründeten selbständigen Konzentrationslagers unter besonderer Berücksichtigung seiner Auflösun-gsphase (Clausthal-Zellerfeld: Papierflieger, 1997); and most importantly Jens-Christian Wagner, Produktion des Todes: Das KZ Mittelbau-Dora , ed. Stiftung von der Gedenkstätten Buchenwald und Mittelbau-Dora (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2001).

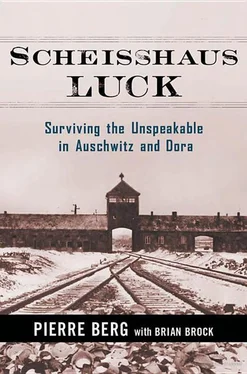

As a recent immigrant to the United States, Pierre Berg wrote down his memories of wartime captivity in his native French. He started this memoir in 1947 with no immediate thoughts of eventual publication and remained somewhat reluctant, after its rejection in 1954 by the Saturday Evening Post , to publish it fifty years later. In the early 1950s, a University of California, Los Angeles, graduate student translated the French original into English under the title, “The Odyssey of a Pajama,” but Mr. Berg did not believe that the translator did justice to the nuances of his testimony. In preparing this testimony for publication, Mr. Brock combined “Odyssey” with extensive interviews conducted over three years. I have compared both versions and can attest that this memoir is faithful in most respects to the original, except that this version helpfully elicits detail that was glossed over in the original. Regrettably, Mr. Berg misplaced the French original manuscript, but the Saturday Evening Post’s rejection letter of 16 April 1954 helps to date Mr. Berg’s original English account. {8} 8 8. Pierre Berg, “Odyssey of a Pajama” (unpub. MSS, 1953); Berg, telephone interview, 13 June 2004.

Although as literature or history his memoir cannot be compared with Primo Levi’s and Elie Wiesel’s canonical Holocaust texts, Survival in Auschwitz and Night , Mr. Berg’s Auschwitz experience reinforces these famous testimonies. Like Wiesel and Levi, Mr. Berg toiled at I.G. Auschwitz under unspeakable conditions in 1944. Like Wiesel, he was a teenager, but three years older and already well traveled. Like Levi, he drafted his original account shortly after the war, when his memory of events was most vivid.

An atheist like Levi, he therefore did not situate his traumatic experience in terms of theodicy, as did Wiesel. Like Levi’s The Reawakening , Mr. Berg recounts his odyssey back to civilization and his not-altogether-pleasant encounters with Soviet troops. One striking feature of this account absent in Levi’s and Wiesel’s writings is Mr. Berg’s unmistakable cynicism. {9} 9 9. Elie Wiesel, Night , trans. Stella Rodway, foreword by François Mauriac, preface by Robert McAfee Brown (New York: Bantam, 1986 [1960]); Levi, The Reawakening (New York: Summit Books, 1986 [1963]). On the Soviet occupation, see Norman M. Naimark, The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945–1949 (Cambridge, MA, and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1995); and Antony Beevor, The Fall of Berlin 1945 (New York and London: Viking Penguin, 2002).

In the interest of full disclosure, I must confess one reservation about this account. Mr. Berg insists that he saw Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler at I.G. Auschwitz in the summer of 1944. No known primary source verifies this claim. Himmler’s recorded visits took place on 1 March 1941 and 17 July 1942. Himmler’s first visit concerned the expansion of Auschwitz, in order to meet the labor needs of the I.G. Farben plant, which had yet to break ground. The second combined an inspection of the I.G. construction site with a tour of the Birkenau killing center, then not yet the center of industrial mass murder it was to become in 1943 and 1944. It is likely that in 1944 Mr. Berg saw one of Himmler’s many doppelgängers . {10} 10 10. For the recorded Himmler visits, see Danuta Czech (comp.), Auschwitz Chronicle, 1939–1945 (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1990), pp. 50–51, 198–199.

Читать дальше