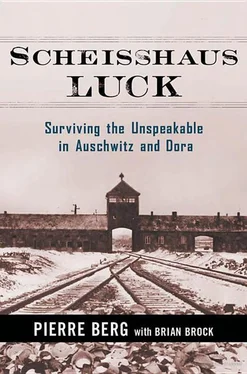

The camp’s fifth phase took place when the war that Hitler unleashed turned decisively against him, with Allied counteroffensives in the Soviet Union, North Africa, Italy, and, ultimately, northwestern France. The German war economy thereupon entered the so-called total war phase, with the rationalization of war production under Armaments Minister Albert Speer, the mass mobilization of foreign workers under Fritz Sauckel, and the deployment of camp labor in private German industry under the SS Business Administration Main Office (SS- Wirtschafts Verwaltungshauptamt , or WVHA). In connection with the latter, I.G. Farben’s erection of the Monowitz camp, discussed in detail below, furnished a model for other subcamps, with the location adjacent to, or inside, factory grounds. By late 1944, camp labor was the principal untapped workforce remaining to the German war economy, with hundreds of thousands of prisoners dispatched to work in construction, bomb disposal, and manufacturing. In the name of economic efficiency, the SS-WVHA attempted to militate against the effects of SS “sport” as practiced by Eicke commandants. The results were mixed and the WVHA did nothing about the annihilation of physically exhausted prisoners or the mass murder of able-bodied Jews during Operation Reinhard. In order to exploit their labor more extensively, private industry modestly improved detainee treatment.

The camps’ last phase, 1944 to 1945, witnessed the disastrous evacuations or “death marches” of malnourished and weakened prisoners from territories adjacent to front-line areas. As Mr. Berg’s account demonstrates, these marches often assumed an inertia of their own, as the SS marched their exhausted victims with little sense of direction, except to get away from the Allies. Lest the proximity of Allied planes and troops raise morale, the SS warned more than once that their last bullets were reserved for the prisoners. {15} 15 15. On the direction of the German war economy, compare Alan S. Milward, The German Economy at War (London: University of London Athlone Press, 1965); with R. J. Overy, War and Economy in the Third Reich (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994). On the SS-WVHA, Allen, The Business of Genocide , passim . Christopher Browning, Nazi Policy, Jewish Workers, German Killers (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 86.

♦ ♦ ♦

The Interessengemeinschaft Farbenindustrie Aktiengesellschaft (Community of Interests, Dye Industry, Public Corporation, or I.G. Farben) inaugurated its Auschwitz project during the camp system’s fourth phase. Preparations for the chemical plant began during the critical nine months between Germany’s frustration in the Battle of Britain in September 1940 and Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union, which started on 22 June 1941. It is easy to lose sight of these two strategic facts, which are significant for understanding how rapidly the conditions for planning this complicated project changed in wartime Germany. With the Luftwaffe’ s defeat in the Battle of Britain, the Reich demanded that I.G. Farben expand synthetic rubber (Buna) and oil production in the expectation of a prolonged war, despite the firm’s well-known concern about the construction of excessive production capacity. Royal Air Force Bomber Command’s raid on the second I.G. Buna plant at Hüls in the fall of 1940 reinforced government fears of an aerial threat against Germany’s small but strategically vital synthetic rubber supply, which led to more insistent calls for the construction of an eastern Buna plant, at relatively safe remove from Allied bombers. {16} 16 16. “Safe remove” is a relative term, because Edward Westermann demonstrates that in 1941 the Royal Air Force’s Wellington bombers had the hypothetical range to attack Auschwitz. See his “The Royal Air Force and the Bombing of Auschwitz: First Deliberations, January 1941,” HGS 15:1 (Spring 2001), pp. 75–76, 78.

Careful surveys by Buna expert and I.G. Vorstand (managing board) member Dr. Otto Ambros in December 1940 revealed a huge stretch of land in the village of Dwoŕy, at the nexus of the Vistula, Sola, and Przemsza Rivers as the optimal site. Its location five kilometers from the new Auschwitz concentration camp nursed unproven allegations, at Nuremberg and later, that the firm selected the site exclusively or partly because of its proximity to “slave” labor. The executives did not discuss the labor issue, however, until convinced of the site’s long-term viability, which included access to essential raw materials, electrical power, excellent rail communications, and space for future growth. An oil firm’s previous bid for the same property led Farben to graft oil production onto the synthetic rubber project. For the German chemical industry, this decision amounted to an unprecedented amalgamation of low-temperature polymerization with high-temperature/high-pressure hydrogenation. The Nazi Four-Year Plan (VJP) chief, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, ordered the firm to utilize Auschwitz prisoners in the construction of the war plant. Göring’s assistant, Dr. Carl Krauch, VJP’s authority on chemical questions and titular head of the I.G. Farben Supervisory Board ( Aufsichtsrat ), later boasted that he had secured camp labor on the firm’s behalf.

As historian Peter Hayes points out, evidence has not emerged to date to demonstrate that the initiative for requesting slave labor rested with I.G. Farben. {17} 17 17. Peter Hayes, Industry and Ideology: IG Farben in the Nazi Era , 2nd ed. (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001), pp. xii–xvi; Joseph Robert White, “IG Auschwitz: The Primacy of Racial Politics (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2000), p. 30; hereafter, White, “Primacy.”

However, once committed to working with the Nazi SS, I.G. quickly adjusted to the exploitation of Auschwitz labor. The project broke ground in April 1941, when the first prisoners trudged five kilometers to the building site under armed guard. The managers and German workers increasingly viewed the prisoners in SS terms, well before the first Jewish detainees arrived at the I.G. building site in July 1942. A comment by construction chief Max Faust about Polish civilian workers, in December 1941, indicated the pernicious effect of the SS on I.G.’s thinking:

Also outrageous is the lack of work discipline on the part of Polish workers. Numerous laborers work at the most 3–4 days in the week. All forms of pressure, even admission into the KL [concentration camp], remain fruitless. Unfortunately, always doing this leaves the construction leadership with no disciplinary powers at its disposal. According to our previous experience only brute force bears fruit with these men. [Emphasis added.] {18} 18 18. Faust quotation in T-301/118/NI-14556(S)/708, IG Auschwitz Weekly Report No. 30, 15–21 Dec. 1941.

Much as I.G. Auschwitz was problematic without Germany’s reversals of fortune in the summer of 1940, it would never have been undertaken if agreements had not been made before the launching of Operation Barbarossa. Contrary to certain postwar claims, I.G. executives did not know about the Führer’s decisions for aggressive war. Operation Barbarossa disrupted their timetables because the German army’s monopoly on the railways in the summer of 1941 cost almost four months of irreplaceable construction time when the start date for oil and rubber production was scheduled for the spring of 1943. With every passing month, the target slipped further away. Unrealistic timetables and frustration over the Krauch Office’s lack of empathy for local conditions contributed to I.G.’s willingness to resort to barbaric SS methods. The failure of Barbarossa in December 1941 led the Nazi regime to reassess its construction priorities, with the closure of projects in the early stages unlikely to contribute to “Final Victory.” Although the Auschwitz project had not progressed very far, it received strong endorsement from Göring, Himmler, and Albert Speer. {19} 19 19. On management’s frustration with the Four-Year Plan authorities, White, “Primacy,” pp. 50–51. On “Crimes against Peace” allegations against IG Farben, Josiah DuBois, The Devil’s Chemists: 24 Conspirators of the International Farben Cartel Who Manufacture Wars (Boston: Beacon Press, 1952); and Mark E. Spicka, “The Devil’s Chemists on Trial: The American Prosecution of IG Farben at Nuremberg,” The Historian 61:4 (Summer 1999): 894.

Читать дальше