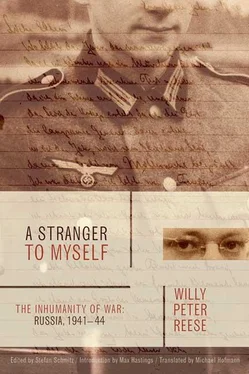

Willy Reese - A Stranger to Myself

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Willy Reese - A Stranger to Myself» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, military_history, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Stranger to Myself

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-42999-875-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Stranger to Myself: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Stranger to Myself»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is an unforgettable account of men at war.

A Stranger to Myself — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Stranger to Myself», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Willy Peter Reese

A STRANGER TO MYSELF

The Inhumanity of War: Russia, 1941-1944

Foreword

For at least a generation after the conflict ended, the Western Allies sustained a historical image of the struggle against the Nazis in World War II that began with blitzkrieg and the Battle of Britain in 1940, then traced the campaigns in North Africa and Italy, followed by D-day in 1944 and the drive of Eisenhower’s armies toward triumph on the Elbe. But little was known and less understood about the vast, misty struggle in the East between 1941 and 1945.

Today we have achieved a better perspective. We can see that the contest between the rival tyrannies of Hitler and Stalin was the decisive clash of the war, to which all else was subordinate. The United States made a critical contribution to the Soviet war effort, supplying aluminum, trucks, canned meat, radios, boots, and much else, without which the Red Army’s advance to Berlin would have been difficult, if not impossible. It was the Soviets, however, who paid the overwhelming blood price necessary to defeat the Nazis, suffering the loss of some 27 million citizens against 1 million dead in the United States, Britain, and France combined. American and British ground forces killed some 200,000 Germans in North Africa, Italy, and Northwest Europe. The Soviets killed approaching 4 million.

There was never a low-cost shortcut to defeat a power as highly motivated, industrially mighty, and militarily proficient as Hitler’s Germany. A long campaign of attrition was indispensable. It was fortunate for the peoples of the United States and Britain that this took place in the East. Implicitly recognizing Russia as the epicenter of bloodletting, the U.S. Chiefs of Staff made the decision to create only a relatively small U.S. ground army. General George Marshall wrote to Secretary of War Henry Stimson in May 1944: “We… have staked our success on our air superiority, on Soviet numerical preponderance, and on the high quality of our ground combat units.” Marshall might have added: “and on the willingness of the Soviets to accept the overwhelming burden of ground casualties.”

A degree of sacrifice was demanded from the soldiers of the two tyrannies that never could have been made by those of the democracies. If Britain had been invaded by the Germans in 1940 or 1941, it is impossible to imagine, however bravely defending soldiers might have fought, that British civilians would have eaten one another rather than surrender. Yet that is what the defenders of Leningrad did from 1941 to 1942. Marshal Georgi Zhukov was probably the greatest commander of the war, yet his feats of arms were achieved by the exercise of a ruthlessness unthinkable in Dwight Eisenhower’s armies. When Zhukov led the defense of Leningrad, he stationed tanks behind his own front not to kill Germans but to shoot down any of his own men who sought to flee. The Red Army shot 167,000 of its own men for alleged desertion or cowardice in 1941–42 alone.

The most important “if” of World War II is to consider how long it might have taken to break Hitler’s dominion of Europe, if he had not chosen to invade the Soviet Union. From the outset, the creation of an Eastern empire, the pursuit of lebensraum for the German people in the vast expanses of Russia, was central to the Nazi program. Hitler told his generals that a single campaign would suffice to crush the rotten edifice of bolshevism. He was extraordinarily ignorant of the industrial power of the Soviet Union, and rejected evidence of its potential. When the Wehrmacht suggested early in 1941 that Russia was already building more tanks and aircraft than Germany, Hitler swept aside the claim, though in truth Axis intelligence estimates of Russian production were too low.

Any notion that Germany’s generals were not complicit in Nazi atrocities can be dismissed after an examination of staff studies made before Operation Barbarossa was launched. German plans required the systematic starvation of millions of Soviet subjects, to remove their grain and foodstuffs westward to feed the German people. There is no evidence that Hitler’s senior commanders raised any objection to this diabolical vision. The purpose of Germany’s war in the East was to enslave the Soviet peoples, no more and no less.

Yet even the Führer suffered moments of apprehension about war with Russia. When Goering sought to flatter him before Barbarossa, asserting that his greatest triumph was at hand, Hitler sharply rebuked his marshal: “It will be our toughest struggle yet—by far the toughest. Why? Because for the first time we shall be fighting an ideological enemy, and an ideological enemy of fanatical persistence at that.” And one day at the Wolf’s Lair, Hitler’s headquarters in East Prussia built expressly for the invasion, he voiced unease to one of his secretaries about what lay ahead: “We know absolutely nothing about Russia. It might be one big soap bubble, but it might just as well turn out to be very different.” The German army, which attacked at three a.m. on the morning of June 22, 1941, possessed 140 divisions, of which 17 were armored and 13 mechanized, with 7,100 guns, 3,300 tanks, 2,770 aircraft—and 625,000 horses. In a rare invocation of any higher power than himself, Hitler concluded a message to his three-million-strong host: “May the Lord God help us all in this struggle!”

Within a week, the armies of Leeb, Bock, and von Rundstedt were deep inside Russia, sweeping aside the ruined divisions of Stalin, taking prisoners in the hundreds of thousands. Guderian’s armored spearheads had advanced 270 miles. Staff at the Wolf’s Lair asked the Führer why he had not troubled to provide even a pretext for his assault, far less a declaration of war. “Nobody is ever asked about his motives at the bar of history,” Hitler answered contemptuously. “Why did Alexander invade India? Why did the Romans fight their Punic wars, or Frederick the Great his second Silesian campaign? In history it is success alone that counts.”

Some officers on Hitler’s staff suffered their first spasms of doubt about the rationality of their leader during those weeks of triumph in Russia. Perceiving victory, Hitler instructed his planners to prepare a blueprint for an onward march to British India. Thoughtful senior subordinates began to understand that their nation was led by a man who possessed no ultimate vision of a peaceful universe. His only policy was unremitting struggle, until there were no enemies left to resist his hegemony.

Private Willy Reese, the author of this memoir, joined the German army in Russia that autumn of 1941, just as the heady sensations of success were being replaced by stirrings of fear. The enemy’s resistance was stiffening. An awareness of the illimitable scale of Russia was seeping through the ranks. The first frosts of fall were harbingers of the deadliest foe of all—winter. Hitler had made no provisions for a long campaign, least of all to supply arctic clothing to his soldiers. When cold such as men had never known began to grip their bodies, to seize up their weapons and vehicle engines, in desperation they were driven to line their clothing with newspapers, for they had nothing else. Shortages of fuel, ammunition, spare parts, aircraft, and bombs started to assail the German armies, in the absence of planning for long-term war production.

Meanwhile, on the other side, the men and women of Mother Russia were accomplishing miracles of endurance and sacrifice to sustain their own struggle. Whole factories were shipped by train beyond the Urals, machinery reassembled in the icy wastes of Siberia, where workers labored, sometimes without benefit of roofs, to build tanks and planes to resist the “fascist hordes.” Those who weakened were shot or dispatched to the camps of the Gulag, where they died of cold and hunger in the hundreds of thousands. Raw recruits were driven into action unarmed, with orders to pick up the rifles of the dead. Stalin’s commissars vied with Hitler’s soldiers in mercilessness. When Russians retreated, they burned the villages of their own people, to leave no shelter for the invader. When Russians were captured by the Germans, many were killed out of hand, while others were conscripted as porters and auxiliaries for Hitler’s legions.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Stranger to Myself»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Stranger to Myself» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Stranger to Myself» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.