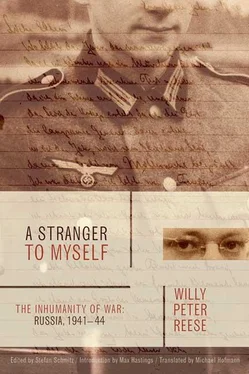

Willy Reese - A Stranger to Myself

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Willy Reese - A Stranger to Myself» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, military_history, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Stranger to Myself

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-42999-875-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Stranger to Myself: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Stranger to Myself»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is an unforgettable account of men at war.

A Stranger to Myself — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Stranger to Myself», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I drifted like a shipwrecked sailor through the calms of fate. I was no longer a citizen of the world and not yet a soldier. On my twenty-first birthday I received my call-up for the beginning of February. [4] Reese confuses his twenty-first birthday with his twentieth, on January 22, 1941. His error is presumably attributable to the chaotic circumstances attending the writing. However, Reese’s cousin Hannelore thinks he may have deviated deliberately from conventional dating and used the date of his birth as his first birthday to make himself a year older.

I gave up my job, gathered together my manuscripts, locked away my diaries, and burned the fragments. Restless days without real activity dribbled between my fingers like sand. My bridges to the past broke; there was no path into the future. No star lit my way. Without hope, but not despairing either, tired and somehow feverish, I got through the emptiness of the waiting period.

One night began like a thousand others. But beneath its stars the change began. I dreamed of the threshold of a new life, and by morning I stood before my destiny as a different person.

My mother was asleep. The night wind cried outside, showers of rain danced across the roofs, and my reading light burned with its friendly glow. I sat over blank pages, pondered and asked, dreamed and sought, wrestled with gods, angels, and demons. And understood.

At first there was nothing but fear and foreboding. We stood at the gate to no-man’s-land and felt the nearness of danger and pain. The years of darkness were beginning, as the stars had decreed. Like beggars, we left behind the wreckage of our youth, freedom, love, mind, pleasure, and work. We were required to subject our own lives to the will of the age, and our destiny began like a tale of duress, patience, and death. We could not escape the law, there was a breach in our unfinished sense of the world, and like a dream, the march into the other and the unknown began, and all our paths ended in night.

Nothing could be more antithetical to my nature than having to become a soldier, to be anonymous among strangers, a toy at the whim of commands and moods, than having to learn the use of weapons with which I would fight one day for a view of the world that was repugnant to me, in a war I never wanted, and against people who were not my enemies. Like a condemned man, I hesitated on the steps to the scaffold and felt the sword graze my neck. The judge had broken the staff over me, and in my powerlessness I accepted his sentence.

That was my abdication.

I smoked; I wrote a line; I drained a glass of wine. The clock ticked; the light flickered along the spines of my books and on the piano. There were aromatic pine twigs in a vase, and Christ’s thorn flowering. Hours dropped into the sea of time. The night advanced, and I kept my vigil, pondered, and dreamed.

The terror of the army years ahead left me no rest. I thought back on the last months of my own life. Like a hungry man facing a long period without food, I hastened through books, concerts, plays, and parties, hectic youthful amours, and thoughtful hours in the garden of youth. But that night, music brought me no consolation, comedy no forgetting of self, tragic drama no reconciliation with my own fate. Every instance of beauty served only to heighten the pain of farewell, and even wine sharpened the anguish of my thoughts. I leafed through records, memoirs, and accounts of the previous generation’s world war, looking for a stance, a way to confront what could not be averted, to know what awaited me, and to understand the war, to learn my own part in it, and to force conflict, danger, and death into my sense of the world. But my reading was as unavailing as my conversations with myself and as every conversation with others, in the shade of melancholy and laughter.

I switched off the light, pulled on my coat, and quietly closed the door after me, so as not to wake anyone. The cool night wind riffled through my hair. The moon was hidden behind the clouds, no streetlight lit my way, and there was no one abroad. I wandered through streets and lanes like a stray dog. Everything I passed carried associations of longing and adventure, despair and mania. I went home and once more sat pondering in the ring of lamplight. Midnight came, and I was still up.

In the beginning was suffering. We put down the masks we had worn in the early light, draped the mirrors of our being and of our vanity, renounced happiness and the growth of the soul, and took on the features of anonymity. We had the feeling: It had to be this way. We had a lot of past history to atone for; now fate made us acquainted with the form of our repentance. We accepted it, like a monk the scourge. Under the mask of a soldier, we settled our debt, and to atone for past lives of deception, frivolity, and illusion, we consecrated ourselves to pain and danger. We were ready to suffer.

Travel was not in my thoughts, any more than adventure, sowing seeds, or a secret maturation.

The clock hands spun around. The hourglass scattered its sand. The distant roar of mines, mills, and ports beat against the window. Footfalls echoed away. The loving and the lost were all long since asleep. My room became an island in the cosmos; this was where the light burned for my solitary thinking, my questioning, and my guessing.

The future was determined by the years ahead, of soldiering. Our fate disentangles itself, and the form acquires definition in what is to come. We were looking for the future. We had a lot to offer and to desire, and now all streets led into life. Fate was something vague that had barely touched our friends, encounters, books, and dreams. As yet we were not marked by anything substantial, anything experienced and lived. But now pitiless life would shape us. We would ripen in denial, survive in hostility, and preserve what was ours in battle. War, the father of all things, was showing us the way. Questions and interpretations loomed in the distance, and we guessed at a good outcome. Our essence was ripening within us; nothing divine could be taken from us, so long as we kept faith with our humanity. The man would emerge from the wearer of masks, being from appearance, and so would stand before God.

I accepted the necessity of what lay ahead. I no longer saw my soldier’s time as a cross to bear. I was all set to live.

My mother awoke. She saw there was a light on in my room, and she came in and silently stroked my hair. Then I was once more on my own. I brought more wine, filled my glass, drank, and sighed heavily.

I didn’t want my years of destiny. All the powers and forces within me refused to allow the strange, the hostile, to enter. The future remained a hell, and my assent did nothing to diminish my fear or struggle. Only my suffering and hoping helped. Nothing beautiful, lofty, or pure happened in no-man’s-land. God did not dwell on battlefields, and the spirit as much as the body died in the trenches. Death held sway in war. What was best in me would be destroyed, and only what was rejected would molder away. If I ever came home, then a different man, destroyed, marked for all time, someone transformed, would stand before the mirror. Then I would wear the brand of death and lead a ghostly existence with the dead in twilight and night.

I emptied my glass. My head ached; my hands shook; my heart beat irregularly. The night was still blue and windy, and I found peace.

Life would not permit of any no. Even the most terrible thing wanted to be sanctioned by an amen. I would have to learn to want destruction, to reject being in deed, as I had often done in word and thought, and in this way to give a grand affirmation to anything that might happen to me. I would have to become as the law decreed, to live or die as my star ordained. No refusal, no will, could change my destiny. Life would be lived whether I wanted or no. I just had to live it, to be it.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Stranger to Myself»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Stranger to Myself» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Stranger to Myself» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.