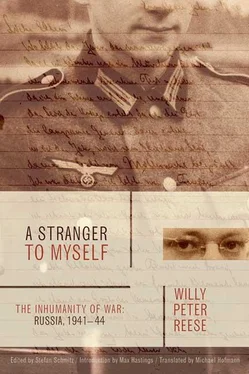

Willy Reese - A Stranger to Myself

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Willy Reese - A Stranger to Myself» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, military_history, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Stranger to Myself

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-42999-875-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Stranger to Myself: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Stranger to Myself»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is an unforgettable account of men at war.

A Stranger to Myself — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Stranger to Myself», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We are war. Because we are soldiers.

I have burned all the cities,

Strangled all the women,

Brained all the children,

Plundered all the land.

I have shot a million enemies,

Laid waste the fields, destroyed the churches,

Ravaged the souls of the inhabitants,

Spilled the blood and tears of all the mothers.

I did it, all me.—I did

Nothing. But I was a soldier.

At the time Willy Peter Reese wrote this poem in 1943, he had been serving on the Eastern Front for two years. Pencils and paper, which were sent to him at the front by his mother, were his weapons against the craziness of this murderous campaign. He wore the uniform of a rank and file soldier in the Wehrmacht. He had four medals and orders across his chest, among them an Iron Cross, II Class. He didn’t mutiny or run away. But he wanted to be a witness.

Now euphoric, now depressed, always tormented by lice and with an advanced craving for alcohol, Reese sets about turning his notes and memories into a single coherent text. In tiny handwriting, using every square centimeter of the page, he writes whenever he can, often by the light of his cigarette, as he crouches behind his gun. Repeatedly, he gets into arguments with the other soldiers about the single lamp. On the run from the Red Army, though sick with hunger, he saves his letter paper and leaves the butter behind. “That’s superfluous, but writing I need to live.” In his diary, which he later uses as a source for his manuscript, he notes: “The only thing that gives me a personal will to survive is my duty to express this war, and to complete my fragmentary works.”

He did it. On home-leave at the beginning of 1944, he types up 140 pages on thin A-5 sheets. He is just twenty-three years old, and nothing like the young man who was drafted into the Wehrmacht at the beginning of 1941. The civilian Reese writes poems and plays, draws, composes music, delights in nature. He corresponds to the point of caricature with the image of the German “Dichter und Denker,” the poet and thinker he feels himself to be and would like to become. Two years after being drafted, as the Wehrmacht is on the retreat from the Red Army, the sensitive youth, who was nicknamed “Pudding” by the young stalwarts at school, has become a dull veteran: “Who were we?” he asks. “Spiritually ravaged—nothing but a sum of our blood, guts, and bones.” A Schongeist seeking comfort in the bottle, and mocking himself as a “genius on distalgesics.” But he remains a scrupulous chronicler of his own decline. He writes down what millions of Wehrmacht soldiers have suppressed and remained silent about.

“I’m collapsing under so much guilt—and I’m drinking!” he complains in September 1943, as his unit, fleeing the Red Army, lays waste the land, blows up factories, enslaves the people, destroys the harvest, and massacres the animals. A little later, on a chaotic transport into the town of Gomel, he describes how the boozy soldateska of the master race make a Russian woman prisoner dance in front of them. They grease her breasts with boot polish. When a woman and her cow are shredded by a land mine, he confides to his diary that he and his comrades had “tended to see the funny side of the situation.” By now, Reese, in some situations at least, much more closely resembles a different cliché than the thinker and poet: that of the German occupying soldier in the East.

His “Confession,” as he subtitles his manuscript, leaves no room for the myth of a squeaky-clean Wehrmacht, misled and misused by a criminal Nazi clique. But it leaves plenty of room for sympathy with the fate of the mass of German soldiers who were on the side of the culprits, while themselves often being victims. Even in Hitler’s war in the East, which was so manifestly criminal, there is not always black and white, not always a clear distinction between good and evil. The scale of the action is so vast that the single man—his pain, his guilt, his experience—is almost invisible.

Reese makes this war understandable, by precisely and soberly describing what happens to him. Even if he can only see a tiny portion of the whole, the character of the campaign shows itself—that and Reese’s capacity to find words for the unsayable. As when he writes of some hanged Russians, who fell victim on some hunt for real or seeming partisans: “Their faces were swollen and bluish, contorted to grimaces. The flesh was coming away from the nails of their tied hands; yellow-brown ichor dribbled out of their eyes and crusted on their cheeks, on which the stubble had continued to grow. One soldier took their picture; another gave them a swing with his stick.” Here is naked, unmediated horror.

What we hear is a writer who describes the principal experience of his generation—participation at the front during World War II—better than almost any other. The sixty-year-old manuscript is not merely an authentic document but a literary discovery.

With his individual experiences, the soldier Reese shows how war destroys the soldiers who wage it. The sufferings of winter marches are made present to us. He gives detailed descriptions of the effect of frost on feet. All at once it seems perfectly reasonable that a soldier, frustrated in his efforts to pull the boots off the body of a Red Army soldier who had frozen in the snow, ends up sawing through the dead man’s lower thighs, and then standing the boots with the stumps in them next to the cooking pot by the fire. “By the time the potatoes were done, the legs were thawed out, and he pulled on the bloody felt boots.”

As unsparingly as Reese writes about the chopped-off legs, so also about the amputation of sympathy. Humanity doesn’t disappear overnight, and it never disappears completely. It is lost piece by piece. The “dehumanizing consequences” of war, which Ralph Giordano has written about, leave a trail through Reese’s text that widens as the war goes on. As he describes his military training in the Eifel Mountains, his lamentations still have the sound of self-infatuated postpubescent warbling: “The plowshare hurt the fallow field of our souls.” Soon it is replaced by the cold constatation of the ravage done to a man at war, without any metaphorical ornamentation.

It persists in the only seemingly absurd wish to get back from home-leave to Russia as soon as possible. “In a sudden fear of anything kind and beautiful, we found ourselves assailed by homesickness. We longed to be back in Russia, in the white winter hell, in pain, privation, danger. We didn’t know what else to do with our lives. We were afraid to be home and now understood what the war had done to our souls.” Not long after the fighting begins, he starts to feel “a stranger to myself.”

Reese is no Nazi and, in spite of occasional prejudices, no racist either. He writes splendidly earthy hymns to the Aryan master race, saying, for instance, how “the round-cheeked plague of Browns / the West in its excrement drowns.” But he is part of Hitler’s invading army. He not only witnesses the sufferings of the Russian victims but participates in the feelings of the German soldiers. He doesn’t seek to prettify his own role. On the contrary: He admits and examines all the feelings that cannot be squared with his sense of self, but that become more mighty as the war goes on.

Along with the state of emergency of body and spirit in the war, there is still euphoria, pride, the feeling of comradeship. And sometimes the understanding of doing wrong is eclipsed by the adrenaline rush of battle. Reese, to whom nothing is stranger than being a soldier, writes: “Men who otherwise were perfectly peaceable characters felt a secret yearning for horrid feats of endurance and arms. The ur-being in us became awake. Spirit and feeling were replaced by instinct, and a transcending vitality swept us away.” Battered by waiting and uncertainty, the “committed pacifist” plunges into the fight. “I am proud of this dangerous life, and of what I have endured,” he boasts to his friend Georg. Sometimes he even feels contempt for those who shy away from battle and danger—only to be revulsed by the change in himself. Between battles and bouts of drinking, he tries to rally himself, and insists that he believes in “what was irreducibly human, some angelic force that was stronger than everything contrary, a sanctuary preserving whatever was best and most characteristic in me across the gulf of the years.” Reese offers not a balanced judgment from some moral high grounds, but the report from a participant, hurting others in a murderous war, and himself suffering. Much remains unfinished and ambiguous. And with that he describes the condition of a man robbed of all certainty.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Stranger to Myself»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Stranger to Myself» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Stranger to Myself» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.