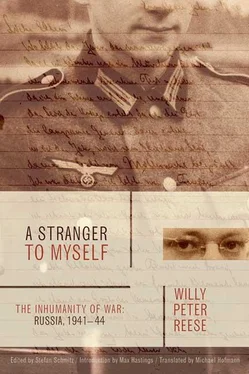

Willy Reese - A Stranger to Myself

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Willy Reese - A Stranger to Myself» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, military_history, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Stranger to Myself

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-42999-875-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Stranger to Myself: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Stranger to Myself»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is an unforgettable account of men at war.

A Stranger to Myself — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Stranger to Myself», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

For decades, no one was interested in Willy Peter Reese’s manuscript. But his memoirs might have helped make the day-to-day reality of the common soldier during the war a part of the general consciousness in Germany. This has not happened yet, even with 18 million men serving in the Wehrmacht between 1935 and 1945. Jan Philipp Reemtsma, the patron of the controversial exhibition on the Wehrmacht, “Crimes of the German Wehrmacht: Dimensions of a War of Annihilation, 1941–1944, ” sees this as a consequence of a social arrangement that has long governed treatment of the Wehrmacht: “There was a sort of unwritten contract: You be quiet about your heroic deeds, and we’ll be quiet about the crimes you perpetrated. In this way—with the exception of what was said within families—there was silence about personal memories.”

The version of things in the minds of postwar Germans was determined not by the accounts of millions of witnesses but by a legend that began to be put about from the day after the war ended in Europe. In the last Wehrmacht report, dated May 9, 1945, the German soldier received a sort of absolution. “Loyal to his oath,” he had “done unforgettable deeds in utmost devotion to his people.” Some senior officers were sentenced by the Allied judges at the Nuremberg trials. But, unlike the SS and the Gestapo, the senior command of the Wehrmacht was not condemned as a criminal organization. In the licensed German press in the years after 1945, there were many reports about crimes perpetrated by members of the Wehrmacht, but most of that generation pushed aside questions about their past. The priority was the rebuilding of Germany; there was only slight interest in shedding light on the past. What there was interest in was a type of comic and adventure writing that dealt with comradeliness, soldierly virtues, and standing the test of enemy fire—all of them subjects on which, from the point of view of the old warrior, no one else is qualified to speak. Nor did the bitter accusations of those children growing up in the ’50s and ’60s against their own fathers lead these to open themselves, and come out with the experiences that had marked their entire lives. Dealings with the Wehrmacht continued to be dominated by politics, thus blocking the view of historical truths and for a long time obstructing the creation of any social consensus about the past.

Today it is an obvious and largely uncontroversial fact that what the Wehrmacht conducted in the East was an unexampled war of devastation. Part of what is needed to understand Reese’s text is an awareness of the environment from which it came. The data about the German rampage in the Soviet Union defy the imagination: some 27 million dead. More than 3 million prisoners of war lost their lives, more than half of those the Wehrmacht had in their power. In the territories of Eastern Europe that were under the control of the German armies, Nazi executioners did away with millions of Jews. It was the greatest abattoir in human history.

Reese responds to his situation as a soldier with powerlessness, fatalism, and submissiveness. Of course he is familiar with Clausewitz’s famous dictum that war is an extension of politics by other means. Of course he senses that he is being used as a cog in a giant murderous machine. The war behind the front line hurts him the most, because it was directed against defenseless people. In a letter to his parents, he says he would feel better as conquered than as conqueror. But he joins in. His feelings and thoughts and witness, which he doesn’t want to relinquish at any price, don’t lead him to insubordination or resistance. In one sketch he draws himself on the way to Russia with giant boots and a grotesquely magnified rifle; farther down on the same piece of paper is another self-portrait, showing himself heading west with a book in his hand and a flower in his buttonhole. Some of the time, at least, the desire for a civilian life remains alive in him. But war to him is like a natural event, an irresistible, elemental force. For humanity, a world war was approximately what an earthquake was to a mountain range, he writes in a letter to his uncle. And so to him, as to so many others, despair at the political and military direction remains without consequence.

Shortly after the beginning of the war, in exile in London, the great publicist Sebastian Haffner estimated the percentage of the German population that was “illoyal” to the regime as high as an astonishing 35 percent, and rising. Haffner gives three reasons why this large number of frustrated and dissatisfied individuals was unable to mount any effective form of resistance: the extraordinarily powerful, unassailable position of the regime, the “non-revolutionary mentality” of the disloyal Germans, and finally “lamentable ideological confusion” and the dearth of new political solutions. All three arguments reflect Reese’s position.

But they probably describe the thoughts of only a minority, albeit a sizable minority. The soldiers in the Wehrmacht comprised a straight cross section of the population. Among them were impassioned supporters of Hitler as much as resolute enemies. But all of them were desperate: It is evident that they urgently needed to find a justification for what they were doing. The Nazis’ racist ideology provided one. Another possible way of making the barbarity tolerable was the recourse to a soldierly sense of duty, as was firmly rooted in the thinking of the war generation. “Help me, God,” Reese, who otherwise was contemplative and self-sufficient, writes in his diary in hours of despair, “to say this yes and Amen , which I have so bitterly fought to achieve, and not to lose it, because out of negation comes the deep, dully burning pain.” This seems to have been the way out for millions of people: a way of consoling themselves, of being able to stand it. From there, it is only a short step to the postwar silence that was meant to stave memory off.

When the war was over, nothing was heard of Reese for decades. Several thousand pages of letters and manuscripts were kept by his mother, as a shrine to her son’s memory. In the course of the war, some things were lost, but most of it she was able to save. She preserved his writing until the time of her death—not even thinking of publication. Reese’s cousin Hannelore, who had looked after the frail old woman in the 1970s, inherited, along with some old furniture, a box of manuscripts. Years later, she set about deciphering the pages, some of them handwritten and yellowing. In 2002—now well past seventy herself—Hannelore began looking for someone to archive Reese’s writing, so that it wouldn’t be lost when she died. She wrote to universities and publishers; few bothered to reply. Then, thanks to Stefanie Korte, a journalist on the staff of the German newsweekly Stern , for which I was working as a reporter, the vital connection was established that led to this book. One afternoon in December 2002, I spent several hours on Hannelore’s sofa in Friedrichs-hafen on Lake Constance. There was cherry tart. The wonderful old lady showed me hundreds of poems, stories, and finally the war memoir. I sensed right away that I was onto something extraordinary. The following summer Stern published a long reportage on Reese’s war experience. The book appeared shortly afterward and shot to the top of the bestseller list. It was followed by a book club edition and then a paperback. In a matter of months, sales had topped 100,000. “This book is a revelation,” wrote the Cologne Stadt-Anzeiger, while the Hamburg weekly Die Zeit greeted Reese’s memoir as “gripping reading.”

Not until the ’90s and a new generation began to ask after the truth did the daily experience of an ordinary soldier become an openly discussed theme. Numerous collections of field post letters are published. But anyone reading them will see a disturbing incapacity to talk about what is experienced. “Many common soldiers were rendered speechless by the grotesque reality of battle” is the conclusion of the Wehrmacht expert Wolfram Wette. [1] Wette, Wolfram, Die Wehrmacht: Feindbilder, Vernichtungskrieg, Legenden, S. Fischer, Frankfurt-am-Main, 2002.

What was needed was “the exemplary individualizing of a ‘little man’ in the uniform of a soldier.”

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Stranger to Myself»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Stranger to Myself» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Stranger to Myself» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.