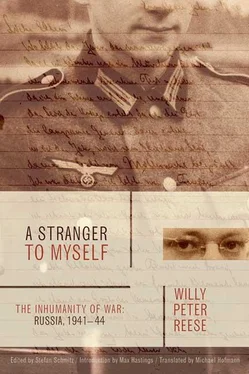

Willy Reese - A Stranger to Myself

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Willy Reese - A Stranger to Myself» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, military_history, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Stranger to Myself

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-42999-875-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Stranger to Myself: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Stranger to Myself»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is an unforgettable account of men at war.

A Stranger to Myself — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Stranger to Myself», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The Germans made a grave error in inflicting barbarism indiscriminately upon those who welcomed them, just as they did upon those who resisted. Many Ukrainians and other Russian subject peoples detested Stalin and Moscow’s tyranny and were perfectly willing to assist the cause of Germany. Yet when they too found themselves victims of wholesale brutality, there seemed no choice save to resist. Through the years that followed, partisan war behind the front imposed mounting pressure on German supply lines. Attempts to suppress this by mass murder, hostage-taking, and devastation of civilian communities foundered on the Soviet peoples’ extraordinary capacity for suffering.

War made Hitler a fantasist and Stalin a realist. In the first campaigns of 1941 and early 1942, Russia’s dictator sought to direct strategy himself, and even to micromanage battles. He was personally responsible for many disasters. Yet by 1942, he had learned the lesson. Without sacrificing a jot of power over the Soviet people, he began to delegate military authority to able commanders—Zhukov, Konev, Rokossovsky, and their brethren—and to be rewarded with victories. These Soviet marshals were terrible men working for a terrible master. Militarily, they were gifted brutes. Yet perhaps only such people could have stemmed the Nazi tide and begun to roll it back. Stalingrad in the winter of 1942 was the turning point of World War II, while Kursk in July 1943 represented the last major effort by Hitler’s armies to reverse the tide of defeat, with 2,400 tanks and 700,000 men thrown into a titanic encounter with 1.3 million men and 3,400 tanks of the Red Army, which the Germans lost.

For the men who fought on the Eastern Front, which often extended to 3,000 miles and more, their worst reality was that there was no escape save death. Germans and Russians alike, committed to action in June 1941, were expected to soldier on through the shocking heat and dust and mosquitoes of high summer, into the piercing colds of winter and beyond, with wounds offering a man’s only chance of respite. German soldiers like Willy Reese were granted occasional leaves, but Russian soldiers could hope to see their homes again only when they had first seen Berlin.

On the Western Front, German and Allied soldiers would sometimes take pity on one another, not least by allowing medical staff to minister to the wounded on the battlefield. But in the East, mercy was unknown. An SS panzer unit woke one morning to find one of its own officers lashed to a haystack in the midst of the Russian positions. He had been taken prisoner during the night. A propaganda loudspeaker called upon the Germans either to surrender or see the haystack burn. They watched the haystack burn. Following that incident, the panzers’ commander ordered that no prisoners should be taken for a month.

Atrocity piled upon atrocity. Mutual hatred created a clash of elemental passions, of a kind few American or British soldiers ever knew in their own campaigns. As the Germans were driven back toward their own frontiers, through 1943 and 1944, they fought with stubborn despair. They knew what their own nation had done to Russia, and what manner of enemies were the Russian people. They could anticipate with terrible certainty the fate awaiting Germany if Stalin’s armies broke through. Here was the central motivation of Hitler’s armies in the last phase of the war, when all hope of victory was gone, along with any belief in the omniscience of the Führer. Millions of soldiers knew that if they were captured by the Soviets, they could expect to die as slaves, just as Russian prisoners were dying in German hands—more than 3 million of them. If they fled the front, they possessed little chance of escaping the attentions of the military police, the kettenhunden, who would deliver them to either a penal battalion or a gallows.

Willy Reese’s own mood sometimes approached hysteria, in a fashion widely expressed in contemporary letters from the front written by German soldiers. The singer Wilhelm Strienz performed requests from frontsoldaten on his hugely popular forces radio show. A line in one of his most celebrated sentimental numbers ran: “Soldiers now crave sleep, not dreams.” Fatalism, together with self-pity about their own predicament and that of their society, was the presiding theme among Hitler’s people, as Nazi dreams of world conquest were supplanted by an expectation of annihilation.

From beginning to end, the Eastern Front consumed the vast bulk of German military resources. Britain made much of victory at El Alamein in November 1942, in which just three German divisions were committed while 180 Axis formations were fighting in Russia. On D-day, Germany deployed 59 divisions in the west, while 156 remained in the east.

To this day, Red Army veterans are contemptuous of the Western contribution to the war. Many of them remark that they were fighting for three years before the first soldiers stepped ashore in Normandy. German veterans profess an admiration for the Russian soldier, which they seldom concede to his Western counterpart. In particular, they acknowledge the Russians’ prowess as night fighters. Even in periods of the Eastern war when no big battle was taking place, few areas of the front remained peaceful for long. Relentless patrolling, local attacks, and mortar barrages denied men more than a few hours’ respite from bloodshed, month in and month out. The only respect in which Germans found Russia a more tolerable battlefield than Northwest Europe was that the Soviets never deployed airpower on the same scale as the Anglo-Americans.

Hardly any Germans survived the Eastern Front unscathed. Like Willy Reese, most soldiers suffered wounds and disease that removed them from combat for a few weeks. Then they were sent back. Many were dismayed, on reaching the front, to find that the consolation of comradeship, fighting alongside familiar and sometimes beloved companions, was lost. Former companions were gone, most of them dead. Only those possessed of the deepest reservoirs of will and resilience, as well as luck, could endure. More than a few men found it easier to die than make the effort to survive.

The Eastern Front in World War II is likely to remain the greatest and most terrible military experience in human history, because it is mercifully hard to imagine that it will ever be matched. Never again, please God, will 6 million and more human beings find themselves locked in bloody embrace for four years, amid such extremes of climate as prevailed in Russia. The men who came home from the East were scarred for life by what they had seen and done, as was Willy Reese. Soviet veterans, eking out pitiful pensions, are today deeply alienated from their own society. They feel that what they suffered for their country is unappreciated. Indeed, the new Russia seeks to banish the memory of the Stalin era. Red Army men have a bitter saying: “It would have been so much better if the fascists had won—now we might be living like the Germans.”

When Willy Peter Reese returned from the front, he wrote about his experiences with the heated enthusiasm of an aspiring author. He was sent back only to die at the age of twenty-three. Elderly Wehrmacht soldiers, in their turn, must pass their declining years in the knowledge that they served the cause of the world’s most terrible tyranny, in a struggle that ended in defeat. This helps to explain why far fewer soldiers’ memoirs have been published in Germany than in the United States and Britain, and why those that exist are important historical documents. They record an experience far beyond anything our own democratic societies have known. We should value their lessons accordingly. They stand as testimony to the extraordinarily privileged universe we inhabit today.

MAX HASTINGS Hungerford, England January 2005Preface

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Stranger to Myself»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Stranger to Myself» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Stranger to Myself» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.