Seeking confirmation, Sparky and I raced into the house, where we found Mom sitting at the kitchen table, smoking a cigarette. That was strange. Usually she only smoked on weekend nights when she and Dad had people over for dinner. And when she sat at the kitchen table, she always read a magazine. But it was the middle of the afternoon, there was no magazine, and her gaze slanted up and away into the smoky air.

“Are we getting an indoor swimming pool?” Sparky asked.

Mom scowled and crushed the cigarette out in the ashtray. “What makes you think that?”

“The hole they’re digging.”

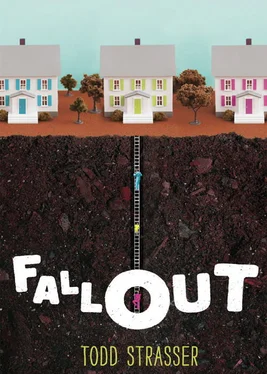

“Your father didn’t tell you? It’s a bomb shelter.”

“What’s that?” asked Sparky.

“A place where we can hide in case the Commies drop the H-bomb on us,” I said.

“Why?” Sparky was filled with disappointment.

“You’ll have to ask your father,” Mom said.

Drained of excitement, Sparky and I wandered into the den to wait for Dad to come home from work. The den had a white shag carpet, a white L-shaped couch, and walls covered with whitewashed knotty pine. Dad had made some of the furniture himself using the big DeWalt table saw in the garage. Sparky and I lay down on the carpet. White shag provided excellent ground cover for the wars I staged with my plastic army men, who, hidden in the long white strands, could sneak to within inches of each other before opening fire. The one absolute rule was no eating in the den. Once crumbs got into the shag, they were gone for good unless you went through the long white fibers with a magnifying glass and tweezers. Getting caught eating in the den was almost an automatic spanking.

“Maybe we can get Dad to change his mind,” Sparky said.

“Maybe,” I said, although I had my doubts. I’d learned a little about nuclear war from duck-and-cover air-raid drills at school, but most of what I knew about the Russians came from the Rocky and Bullwinkle Show on TV. Rocky the flying squirrel and his pal Bullwinkle J. Moose were often called upon to foil the sinister plots of Boris Badenov and his girlfriend, Natasha Fatale, who had foreign accents and were no-good spies from a no-good country clearly like Russia.

Americans were a good, peace-loving people. We had a handsome president with a pretty wife, and we wanted to live freely and play baseball and enjoy life. Russia had an ugly leader who most likely wasn’t even married and only wanted to destroy America. The Russian people lived in fear of their leaders and probably weren’t allowed to play sports.

So it would be too bad if we weren’t getting a swimming pool, but maybe a bomb shelter wasn’t such a bad thing, either.

19

Sparky and I have no dry clothes to change into, so we sit naked on the lower bunk with a blanket around our shoulders. I feel proud of my little brother for not making a fuss about wetting himself. After a while everyone is awake again, and Dad cranks the ventilator to get more fresh air in the shelter. Janet sits on the edge of Mom’s bunk and feels her pulse. People stretch and move around. They glance at Mom and at Sparky and me pressed close together, but no one says anything. Paula wrinkles her nose like she can smell what Sparky did, but then whispers to her father, who speaks in a hushed tone to Dad. They may be whispering for Paula’s sake, but everyone knows what they’re talking about. Dad gestures at a bucket with a toilet seat on top of it.

“Won’t it fill up quickly?” Mrs. Shaw asks.

Dad points at the big metal garbage can next to the toilet bucket. “It goes in here.”

Paula starts to cry again. Mr. McGovern hugs her. “It’s okay, honey. Everyone’s going to have to use it sooner or later.”

With her legs squeezed together, Paula leans against him and sobs. I feel bad for her. Maybe everyone will have to use the toilet bucket, but I wouldn’t want to be the first, either.

“For Pete’s sake,” Mrs. Shaw grumbles. I watch in amazement as she pulls up her robe and sits down on the toilet seat. “Don’t look,” she says, annoyed.

I quickly turn away and hear the hard rattle as her pee strikes the bottom of the empty bucket. Soon it becomes a dribble and then stops. Mrs. Shaw focuses on Dad. “Toilet paper?”

Dad goes to a shelf and gets a roll. “I only stocked enough for four people.”

“How could I forget?” Mrs. Shaw snorts. The soft sound of tissue tearing is followed by the rustle of clothes. Then in a gentle voice she says to Paula, “Okay, honey, it’s your turn.”

Paula sniffs.

“Go on,” her father says softly.

“Noooo,” Paula wails, as if she’s in agony. You can’t help feeling bad for her. Dad starts to crank the ventilator again. Only this time it’s for the noise.

“Come on, honey,” Mrs. Shaw says. “I’ll make sure they don’t look.”

Ronnie glances at me and smirks. But he’s being a jerk. Mrs. Shaw stands in front of Paula, and the rest of us look away. When Paula’s finished, she comes out from behind Mrs. Shaw with her head bowed and goes back to her dad, eyes downcast.

“Anyone else?” Mrs. Shaw asks. I have to go and now that some of the others have, I figure what’s the big deal and maybe it will make Paula feel better. So I say me.

“Well, aren’t you the brave one?” Mrs. Shaw says, and I’m not sure whether she means it or is being sarcastic. Since all Sparky and I have to cover us is the blanket, he has to get up with me. Like a four-legged creature, we shuffle over to the toilet bucket. Once again Mrs. Shaw blocks the view and Dad cranks the ventilator. I really do have to go, but I can’t with Sparky standing next to me and all these people around. It’s as if everything down there is blocked, and in an instant I go from the proud feeling of being brave to feeling completely embarrassed, because even with the ventilator going, the others will be able to tell that nothing is happening. That’s when Mrs. Shaw whispers, “Think about waterfalls and garden hoses.”

The next thing I know, pee splashes into the bucket, where it mixes with Paula’s and Mrs. Shaw’s, and I wonder why it was so hard to go before.

Janet goes next, and then one by one, the fathers pee in the bucket, only Dad doesn’t crank the ventilator for them. After a while, the only one who hasn’t gone is Ronnie. I glance at him, but instead of a smirk, his face is scrunched up as if he’s in agony.

Mr. Shaw squeezes his arm. “You better go.”

“Shut up,” he grunts.

A jolt jumps through me like an electric charge. I’ve never heard a kid say that to a parent or any grown-up. I wait for Mr. or Mrs. Shaw to scold him, but there’s only silence until Ronnie lets out a low moan as if his bladder is about to explode.

A moment later, when I hear a gurgle, I assume Ronnie is going in his pajamas. But Dad quickly looks up at the water tank, and his eyebrows practically leap off his head. It’s the sound of running water!

Maybe it’s the relief of knowing we have water or the sound of it sloshing through the pipes, but Ronnie races to the toilet bucket and goes.

twenty

When Dad came home from work, Sparky and I followed him into his and Mom’s bedroom, where he took off his suit, shirt, and tie, removed his brown leather shoes and placed shoe trees in them. Then he unsnapped the elastic garters around his calves that held up his long, thin socks, and put on dungarees, a gray Fruit of the Loom sweatshirt, white wool socks, and old tennis sneakers.

“Are we getting a bomb shelter?” I asked.

Читать дальше