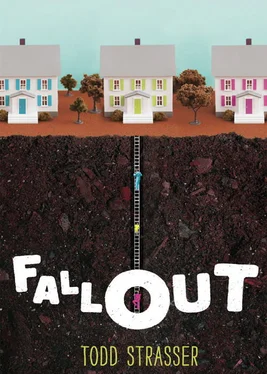

“I’ll tell you at dinner,” he said, and headed outside. In the summer, Dad often did yard work before dinner. Sparky and I followed him into the backyard, where he stopped to look at the hole.

“How deep will it get?” I asked.

“Pretty deep,” Dad said.

“Sure would make a good pool,” said Sparky.

“Yes, it would,” said Dad.

“A pool would be fun,” Sparky said.

“We need a shelter more than we need a pool.”

“Couldn’t it be a shelter and a pool?” Sparky asked.

Just then, Mom called us in. During dinner, Dad told Sparky how there was a chance we might go to war with the Russians.

“Why don’t they like us?” my brother asked. “Did we do something bad to them?”

“They don’t agree with our form of government.”

“What’s that?”

Dad tried to explain, but it was hard to go from what a democracy was to why the Russians would want to blow us to smithereens.

“If the Russians win, will we be their prisoners?” I asked.

“Not necessarily,” Dad said. “A lot of people think that if there’s a war, neither side can win.” He must have seen the confused expressions on our faces, because he added, “Both sides have so many bombs that there’s a good chance we’ll destroy so much of each other’s countries that no one will be able to claim victory.”

That didn’t make sense. Why would anyone go to war if they knew ahead of time that neither side could win? Thus far in the conversation, Mom had remained quiet. Now she slowly shook her head. “Mutually assured destruction. It’s ridiculous.”

Dad leveled his gaze at her. “I agree, but it’s a possibility.”

“Don’t scare them,” Mom said, a bit harshly. The “them” she was referring to was Sparky and me.

“They asked why we’re building a shelter—” Dad began to reply.

“Not a shelter, a bomb shelter,” Mom interjected. “And we’re not building it — you are.”

They stared at each other. Then Mom got up and hurried out of the room. Dad let out a sigh. “Finish your dinner, boys.” He left to go find Mom.

21

As water races through the pipes and into the tank, I hear someone’s throat catch and see Mrs. Shaw hug her husband with relief.

“There was probably an obstruction in the line,” says Mr. McGovern. “The water pressure must have forced it loose.”

Dad takes a glass from a shelf and fills it, then sniffs tentatively before taking a sip. He grimaces.

“What’s wrong?” Mr. Shaw asks. Dad hands him the glass, and Ronnie’s dad tries a little, then spits it at the drain in the middle of the floor and wipes his mouth. “ Achh! It’s awful.”

“You didn’t rinse the system when it was installed?” Mr. McGovern’s question sounds critical.

Dad doesn’t answer.

“Is that bad?” Mrs. Shaw asks with alarm, directing the question to Mr. McGovern. “Will it hurt us?”

Mr. McGovern pauses thoughtfully. “I don’t think so. It won’t taste good, but we won’t have to drink it forever.”

Mrs. Shaw takes the glass from her husband and sips. Her face goes hard. “Well, at least we can wash our hands.”

Dad gazes up at the water tank. “Maybe we shouldn’t. I’m worried about using it for anything except drinking.”

“You don’t think there’ll be more if this runs out?” Mr. Shaw asks.

Dad shrugs. “I don’t know.”

“Actually,” Mr. McGovern begins, then pauses as if he wants to make sure everyone is listening. “Given the circumstances, I suspect we’ll have all the water we’ll need.”

This comment is met with silence. The grown-ups share the kind of meaningful look that makes kids nervous.

“Why?” Paula looks anxiously at her father, who lets out a reluctant sigh like he doesn’t want to give the answer.

But he does. “Because, honey, there probably isn’t anyone else left to use it.”

Paula begins to sob again.

Dad pours just enough water into a bowl so that we can wash our hands. Then he uses a corner of a towel to gently wipe Mom’s face. Sparky and I huddle under the blanket. The sour odor of urine from our wet pajamas mixes with the damp mildew smell of the shelter. I would ask Dad if he’d wash our pajamas, but I know what his answer will be.

He does make a pitcher of Tang. There are only four glasses, so each family shares and Janet gets one for herself. Even with the Tang, the bitter metallic taste from the pipes comes through. By now everyone’s a little hungry, and we eat Spam on the bread and broken crackers Mom brought from the kitchen. The Spam tastes spicy and salty, and everyone drinks more Tang. But Dad’s being careful. Whether on crackers or bread, we each have about half a sandwich’s worth of food and maybe a cupful to drink.

“Herb thinks the water won’t be a problem,” Mrs. Shaw reminds Dad.

Sitting beside Mom, Dad says, “I don’t know how anyone could be certain.”

Mr. McGovern exhales noisily, as if he’s dealing with an idiot. “It’s a gravity-fed system, Richard. It doesn’t depend on electricity or any other kind of power.”

“Willing to bet your life on that?” Dad asks sharply, as if he’s getting annoyed with Mr. McGovern’s attitude. Mr. McGovern exchanges a look with Mr. and Mrs. Shaw, but no one says anything more.

Sparky wriggles under the scratchy blanket. “What about our pajamas?”

Dad shakes his head. “I don’t think so, Edward. They won’t dry down here, and this could be all the water we’ll get.”

“Please, Dad?” Sparky whines.

“I said no.”

“If they put them back on, won’t their body heat eventually dry them?” Mr. Shaw asks.

“Want to try it, boys?” Dad asks us.

Even though Sparky and I are both squirmy and itchy and constantly tugging little bits of blanket from each other, I’d rather be huddling naked with him than put my damp, pee-stinky pajamas back on.

We’ve eaten and gone to the bathroom, and now there’s nothing else to do except sit. Ronnie catches my eye and I know that he wants to talk, but I still don’t know how I feel. He may be my best friend, but my scraped elbows and throbbing knee are a reminder of last night’s fight. All he’s ever done is get me in trouble and make me think about things I don’t want to think about. Maybe it’s good that I’m sharing the blanket with Sparky, because that means I can’t go talk to him.

Dad tries the radio, and again there’s nothing but silence and static.

“Did you test it?” Mrs. Shaw asks. “I mean, before?”

Dad doesn’t answer, which is kind of an answer in itself. Mrs. Shaw lets out a loud, dramatic sigh of disapproval.

twenty-two

It wasn’t long before the hole in the backyard came up to the Negro men’s chests. Now two men shoveled, filling a metal bucket, which the third hoisted out of the hole and dumped into the wheelbarrow. The men also began to encounter large rocks, some the size of basketballs, that had to be pried out of the ground and heaved onto the grass beside the hole.

The men always arrived early in the morning and usually stayed until around five o’clock, when a pickup truck would come get them. There wasn’t room for all three in the truck cab, so one would sit in front and two would climb into the back. The man who drove the pickup was white.

Each day the men brought metal lunch boxes and thermoses. By now they were used to me and Sparky watching and would sometimes nod at us. And sometimes they would carry on a conversation as if we weren’t there.

Читать дальше