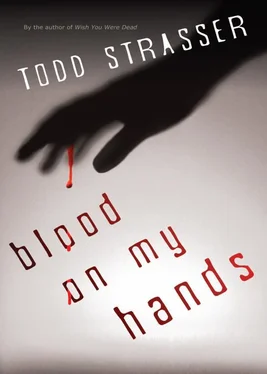

Todd Strasser

Blood on my hands

Copyright © Todd Strasser, 2010

To Lisa Dolan,

who lives and breathes literacy

I would like to thank the following people for their contributions toward bringing this story to life:

Regina Griffin, Greg Ferguson, Dr. Petra Deistler-Kaufmann, Tina Pantginis, and Augusta Klein.

“You know that when I hate you, it is because I love you to a point of passion that unhinges my soul.”

– JULIE-JEANNE-ÉLÉANORE DE LESPINASSE,

French salonist (1732-1776)

“Keep your friends close, and your enemies closer.”

– SUN-TZU, Chinese general and military strategist (~400 BC)

Saturday 11:45 P.M.

IN THE DARK woods behind the baseball dugout, I’m kneeling next to Katherine’s body, my heart racing, my breaths shallow and fast, my emotions reeling crazily at the sight on the ground before me. Katherine is lying on her side, curled up, as if she was cowering from whoever attacked her. Her body is still warm, but there’s no pulse. I know because I just pressed my index and middle fingers against her sticky wet neck and then to her wrist to feel her carotid and radial arteries, the ones the EMTs told me they checked. And that means she’s dead. Dead! It can’t be possible. Katherine… who I’ve gone to school with, been friends-and enemies-with. My stomach hiccups spasmodically and I taste bile burning the back of my throat. I can’t believe that this is happening, that I’ve just touched a dead person, someone I know, someone my own age.

Someone… who’s just been murdered.

The hot bile surges up into my throat again and I manage to swallow it back. Despite the cool autumn air, perspiration breaks out on my forehead and I feel its dampness on my skin. The slightest wisps of moonlight trickle down through the branches overhead, which cast shadows on Katherine’s blood-mottled face. The light illuminates the horrible deep red slashes in her soft pale skin. Her eyes are open, blank, unseeing. I can’t look at them.

Something, barely a glint in the dark, is lying on the ground beside her. I reach for it. A knife. The handle is wet, but this wetness has a different feel than water. Thicker, and both slipperier and stickier at the same time. I look down at the blade, blotched with blood, and can just make out near the handle a brand logo of two white stick-figure men against a square red background. Unwanted thoughts invade my brain-the horrible image of the blade slicing into Katherine’s soft flesh. I feel my stomach churn again, the bile threatening to rise. I swallow hard, forcing it back.

Through the trees, footsteps approach, rustling the brush and branches. People are coming. I feel their shadows looming over me, and I look up at their dark silhouettes.

“You killed her!” That sounds like Dakota’s voice.

What! The words startle like an unexpected punch. “No! What are you talking about? That’s not what happened!”

“Why’d you do it?” another voice demands. In the shadows behind the dugout, there’s a small crowd now. Their dark faces are a blur.

“You know why,” Dakota answers before I can even think of what to say.

There’s a burst of light. Someone’s taken a picture with a cell phone. I look down at the bloody knife in my hand. Oh no! Fear floods through me and I drop it. I didn’t do anything! Just moments ago at the kegger, Dakota told me Katherine had disappeared, and said I should go look for her by the baseball dugout.

There’s another flash. I spring to my feet, wiping my bloody hands on my jeans. How could they think I’d do such a thing? How could anyone do this to anyone?

“Call the cops,” Dakota says.

“No!” I cry. “I mean, yes! You have to call them. But not because of me! I just found her here. I swear!”

People mutter. There’s another flash. I take a step back. They can’t be serious. They can’t really believe I’d-

“Don’t let her go,” Dakota cautions.

“But I didn’t do it!” I blurt.

“God, look who’s talking,” someone says.

“Do you believe it?” says Dakota. “Of all the people?”

The words pierce. Everyone knows why she’s saying that. Because it’s happened before. This is the second time in my life I’ve been this close to a bloodied, battered body. The second time I’ve seen the carnage one person can do to another. Suddenly it’s obvious they’re never going to believe me. Not in a million years.

“Don’t let her go!” Dakota says with more urgency as I back farther from the body.

Panic-stricken, I turn and dive into the dark, running as fast as I can, crashing through the brush, slapping branches out of the way, stumbling on rocks, my face and arms being scratched by things I can’t see.

“Get her!” Dakota yells, only now her voice is more distant.

* * *

They say I always ran. From the time I could walk. It was almost like I went straight from crawling to running. I was the kid in the hall the teachers were always telling to slow down, the one who’d run even when there was no rush. I’m little, only four foot ten and ninety-eight pounds. Coach Reynolds, who’s in charge of the cross-country team, once told me he’d seen my type before. Small girls who could run forever. I didn’t like being thought of as a “type,” but there was some truth to it. I used to see other girls like me at meets. But I’d wonder if they ran for the same reason I did. In my family, it was a matter of survival.

Saturday 11:53 P.M.

I COME OUT of the woods, then dash across Seaver Street and into the Glen. The houses here are big old Tudors with spires, white stucco walls, and leaded windows. My heart is banging in my chest, from both running and fear. Slowing to a jog and weaving away from the bright spots under the streetlights, I know I have to find a place to stop and think. Finally, in a side yard, I see a child’s playhouse. It’s the size of a small shed, with a miniature porch, windows, and a door.

After tiptoeing across the lawn, I gently step onto the little porch and carefully, slowly, pull open the door, hoping it won’t squeak. I’m praying that the people who own this property don’t have a dog that will start barking. It’s dark inside, but with the door open I can make out a small yellow plastic table and two red plastic child-size chairs. I let the door close and find myself in blackness. Can’t see my hands in front of my face. But it’s oddly reassuring. If I can’t see myself, then no one can see me, either. I sit on one of the chairs, press my face into my hands, and take steady breaths, trying to calm down.

But my heart’s still drumming and I still cannot believe what just happened. Katherine murdered?

And now what? I’ve never run away like that before. I never did anything wrong that would have required running. Why did I run? Why didn’t I stay and try to explain? Because they’d see me beside Katherine’s body with that bloody knife in my hand and Dakota saying, Do you believe it? Of all the people?

Of course they’d believe it. After all, two years ago my older brother, Sebastian, made national news by bludgeoning our father nearly to death with a two-by-four, leaving him brain damaged and mute and paralyzed from the neck down. What’s so hard to believe? Like brother, like sister, right?

Into the inky stillness inside the playhouse comes the distant sound of sirens. Dread chills my veins. The police are coming. I can picture what’s happening. Based on the phone calls from kids at the kegger, a code 11-41 has been issued. The boxy red-and-white ambulance is pulling out of its bay at the new town center.

Читать дальше