How ironic that it should have been a drunk driver whose car ploughed into the side of theirs at the junction. Straight through the traffic lights on red. Experts called to give evidence at the trial judged that he had been doing more than sixty. Even more ironic that he had walked away unscathed. In another three years he would be out of prison, with most of his life still ahead of him, able-bodied and fit. A job waiting for him in his father’s business. A forgiving family.

Amy found it difficult to forgive, but she had tried hard not to let it make her bitter. She had lost so much else, that to lose that core of sunshine that lit her personality would have plunged her into a dark world, depressed and defeated, and unable to face the challenges ahead. Challenges that would need all her reserves of courage and resolve and optimism.

But tonight she wasn’t sure how much deeper she could dig into those reserves. She grasped the controller on the arm of her wheelchair and manoeuvred herself back into the attic of the warehouse, closing the French windows behind her and drawing the curtains against the night. Time, she thought, for a glass of red wine to cheer herself up. She went to the kitchen and poured herself one. If only now she could curl up on the settee with a good book.

The electric motor whined as she crossed the floor to gaze for the umpteenth time at the little girl whose face she had recreated. She wasn’t sure about the hair. Something told her — instinct, the thing that MacNeil so hated when it came to analysis of evidence — that Lyn would suit her hair short. Not a bob cut. Something more primal — ragged and spiky. After all, a child from a developing country would not have had access to a stylist. And yet she had been here in London. Living here, perhaps. But not long enough, certainly, for a change of diet to affect her teeth. And there had been no surgery attempted to fix her lip.

Was she adopted? If so, who were her adoptive parents? Hadn’t they reported her missing? Questions, questions, questions. They had been rattling around her head all evening. An attempt, she recognised, to stop her dwelling on other things. But there had been no answers. Only flights of fancy. Speculation. Assumption. She knew no more now than she had this morning.

The phone rang and she crossed the room to answer it.

‘Amy, it’s Zoe.’

‘Hi, Zoe.’ Amy glanced at the time. It was after eleven. ‘You’re not still at the lab?’

‘Yep.’

‘You should have been home before the curfew.’

‘Yeah, well, I’m stuck here now, aren’t I? And it’s all your fault.’

Amy gasped her indignation. ‘My fault! How?’

‘You asked me to run a virology test on the bone marrow Dr Bennet recovered from the skeleton of the little girl.’

‘You’ve done a PCR test already?’

‘I did more than that.’ She sounded pleased with herself. ‘I recovered not only the virus, but the RNA coding.’

Amy experienced momentary confusion. ‘What? You mean you’re telling me she had the flu?’

‘She sure did. And the virus I recovered is definitely infectious. I mean, the pure RNA alone is still infectious. But the RNA and protein together, well, that’s sheer dynamite.’

‘Jesus, Zoe,’ Amy said, alarmed. ‘You should be working in a Level Three lab with infectious material like that.’

‘Yeah, probably.’ There was a hint of a yawn at the other end of the phone.

‘You don’t have lab three facilities there.’

‘Nope.’

‘But you used lab three precautions, right?’

‘Well, not exactly.’

‘Zoe!’ Amy was shocked. ‘You stupid idiot!’

‘Hey, keep your hair on, Amy. It’s cool. Honest. I know what I’m doing. I could have done it in my kitchen.’

Amy was furious. ‘Is Dr Bennet there?’

‘He’s got a couple of autopsies.’

‘Well, get him to call me as soon as he’s free.’

‘Aw, come on, Amy, you’ll get me into trouble.’

‘You should be in trouble, Zoe. You could infect yourself. You could infect everybody in the building.’

‘It’s all locked down and safe as houses. Honest.’ She paused, nursing her silent resentment at Amy’s anger. ‘So I suppose you won’t want to know what else I found, then?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Hah. Got your interest now, haven’t I?’

‘Zoe...’ Amy’s voice carried its own warning.

‘It’s not real.’

Amy heard the words, but she didn’t understand them. ‘What do you mean it’s not real?’

‘The flu virus. It’s not the H5N1 mutant that’s killing everyone. It’s been genetically engineered.’

Amy was having difficulty taking on board the implications of what Zoe was saying. ‘How do you know that?’

‘Well, it’s all just code, right? When you boil it right down to basics, any virus is just a series of letters — code words. And somebody left some words in the code that shouldn’t be there. I mean, for example, you would find the words Stu I AGGCCT and Sma CCCGGG in synthetic polio. And you know these create a restriction site that is easily recognised by treating the DNA copy of the virus RNA with a battery of restriction enzymes that cut the DNA at that site.’

‘Woah! Jesus, Zoe, hold on! Speak English.’

‘I thought I was.’

‘Okay, think molecular genetics for idiots.’

She heard Zoe sighing at the other end of the phone. ‘People have been collecting library sequence banks for the flu virus for years. I’ve got them all on file. Took only a few minutes on my laptop to compare the RNA of the virus we got from the girl with the sequence banks on the hard drive. The introduced restriction sites stood out like a sore thumb. I’m telling you, that kid didn’t just have any old garden-variety flu. She had a twenty-four carat, genetically engineered humdinger.’

Amy sat for a moment replaying what Zoe had just told her. None of it made any sense. ‘Is that what killed her?’ she asked. ‘This man-made flu?’

Zoe blew air through her lips three miles away across town. ‘I haven’t got the first idea.’

MacNeil turned past the deserted South Kensington tube station into Old Brompton Road. The Lamborghini London franchise had been cleaned out long ago. The showroom windows were smashed; the floor space beyond, which had once been graced by some of the most expensive cars in the world, was empty and exposed to the elements. The Royal Bank of Scotland next door was all boarded up, its vaults cleared out by the bank itself and transferred to more secure premises. There was no point in the looters trying to break in, and so they had taken out their frustrations in a multicoloured display of graffiti comprising even more colourful language.

The bench in the tiny triangle of parkland at the road junction was normally inhabited by two or more drunks congregating to share their misery, to drink from cans in paper bags and fill the air with their cigarette smoke and hollow laughter. To MacNeil’s shame, he had almost always heard a Scots voice amongst them. But they were long gone. The soup kitchens were closed, and men raddled by years of drink were easy prey for H5N1.

There was less damage here than in the city centre, less evidence of looting. Old Brompton Road was largely residential with small shops at street level. Pizza Organic, Mail Boxes Etc., Waterstones. Poor pickings compared to the big stores downtown. And no self-respecting looter was going to be seen dead breaking into a bookshop. Still, most of the shops were boarded up, and there were few lights on in the windows of the flats and offices above.

MacNeil dropped down to second gear and cruised slowly along the street checking the numbers. He found Flight’s gallery on the corner of Cranley Place, next door to the steel-shuttered Café Lazeez. The windows of the gallery had been boarded up, and then pasted over with layer upon layer of peeling bill posters advertising everything from mail-order art to underground concerts in unnamed locations. There was some sort of crest above the door on the corner, and in Cranley Place itself, an entrance to the apartments above the gallery.

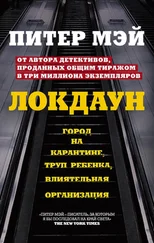

Читать дальше