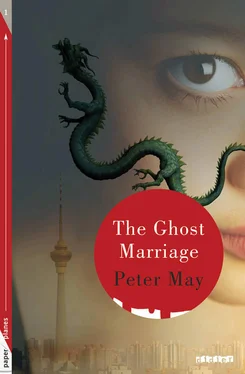

Peter May

The Ghost Marriage

Sweet though it was, the perfume of the incense could not disguise the odour of putrefying flesh. And the summer heat was not helping.

The cadavers were at the back of the room on a long table, surrounded by bowls of fresh fruit, boiled eggs in bowls of rice, dim sum still warm from the steamer, buns, a bottle of chilled white wine running with condensation.

The guests assembled at the far side of the room, near the door, and the window with a view on to the siheyuan courtyard. In the hutong beyond, children played unaware of the bizarre marriage taking place behind high walls.

The spirits of the dead man and his fiancée stood before a temporary altar: paper effigies to be burned, along with paper money, a paper car, and paper furniture that stood outside as comforts to be treasured in the afterlife. A gong sounded in the hands of the priest, and with a swirl of his red robe he placed a ring on the left hand of the paper groom. From the back of the observers, Feng Qi watched as the dead boy’s mother placed a ring on the paper finger of the bride, and he let his eyes return uneasily to the open coffins behind them and the dead girl, whose face was troublingly familiar.

The No. 1 Kindergarten in Anzhenxili was not far from the No. 3 Ring Road, just north of Tiananmen, and the Forbidden City. As she waited for Li Jon, Margaret gazed from a window across the almost unrecognizable cityscape of post-Olympic Beijing, reflecting on how rapidly much of this city had transformed itself from medieval to ultra-modern in the ten years since she first arrived.

She turned at the sound of children’s voices filled with the euphoria of freedom after a long day of educational incarceration. Li Jon wrapped himself around her legs, and she lifted him up into her arms: something she would not be able to do for very much longer. He was growing like bamboo. She brushed dark hair from his eyes and saw only his father in him: fine Chinese features that owed nothing to her fair-haired, blue-eyed Celtic heritage. But he had, she knew, inherited his mother’s fiery, querulous spirit, and she took pleasure from his father’s frustration that he had not transmitted to his son more of his gentle Chinese fatalism.

‘Did you get my iPod, Mommy?’ He spoke English with her distinctive American accent. But also Chinese, like a native. Both she and Li spoke to their son in their native tongues, sending him to this bilingual kindergarten where he would learn to be a citizen of the world — bridging the cultural divide that had so often caused misunderstanding and conflict between his parents.

‘Sure I did, honey. It’s waiting for you back at the apartment.’

He descended from her arms and took her hand, impatient to be home as soon as possible.

But he was forced to temper his excitement by a lady who intercepted them at the front door. She wore blue overalls, and a white cloth cap, a few strands of greasy black hair hanging down from one side of it. Her hands were red and callused, her flat peasant face rough and weathered, with troubled dark eyes. Margaret had seen her before, washing the floor of the lobby with slow, languid movements of her mop.

‘Sorry to trouble you, lady.’ She was strangely formal, half bowing, almost deferential. ‘They tell me you are wife of Section Chief Li Yan.’

Margaret took satisfaction from exercising her increasing skill in Chinese. ‘Then I’m sorry to say they tell you wrong.’ The woman’s disappointment was almost palpable, and Margaret immediately regretted her abruptness. She added quickly, ‘An American woman is not permitted to marry a serving Chinese police officer.’ She pulled the child at her side a little closer. ‘But Li Jon is our son.’

She saw hope flicker again in the woman’s eyes, like the flame of a candle stirring in the wind. The woman reached out a hand to clutch Margaret’s arm, and Margaret could feel the desperation in her bony grasp. ‘Then I beg you to help me, lady.’ She glanced at Li Jon. ‘You are a mother. I am a mother too. But my little girl is gone.’

The apartment block where Li shared his life with Margaret lay to the east of Tiananmen Square, just south of East Chang’an Avenue, in the old British Embassy compound that was now occupied by the Ministries of State and Public Security. It was the same two-bedroomed police apartment he had once occupied with his late uncle. Now he and Margaret and their child lived there, in flagrant disregard of the rules. Only his elevated position as chief of Section One, Beijing’s serious crime squad, had persuaded the authorities to ignore his indiscretion. That, and perhaps the fact that Margaret still occasionally took time off from her lectures in forensic pathology at the University of Public Security to perform key autopsies for the Beijing police.

He pulled the door shut on Li Jon’s bedroom and stood listening for a moment. It had taken him some time, and the reading of a favourite bedtime story, to persuade the child to put away his new video iPod and settle down to sleep.

Margaret had placed bowls of rice and a plate of sweet and sour pork on the table in the living room, and they sat down to eat together with bottles of beer as darkness fell on Zhengyi Road. The light of the streetlamp outside their first-floor window danced as the breeze blew through the leaves of the locust trees that lined the street. But even with all their windows open, the heat remained oppressive and overpoweringly humid. Li’s fresh white shirt was already sticking to him. He wiped the sweat from his forehead with the back of his hand, then ran the palm of it back over his short-cut hair.

‘There are seventeen million people in Beijing,’ he said. ‘Thousands of them go missing every day. They look for work, they don’t find it, they move on.’

‘She’s just seventeen, Li Yan.’ Margaret had no idea why she was playing advocate for the cleaning woman at the kindergarten. Except that the appeal from one mother to another had touched something inside her.

‘Teenagers are always disappearing. Runaways mostly. Unless there is evidence of a crime there is nothing much I can do about it.’

‘Imagine,’ Margaret said, ‘that we were talking about Li Jon.’

Li’s chopsticks paused, midway to his mouth, and he looked at the woman with whom, in spite of every cultural and linguistic obstacle, he had fallen in love. She always knew just what buttons to press. Not that he felt manipulated. It pleased him to think that someone could know him that well, and yet still choose to be with him. Finally he popped the pork into his mouth, masticating thoughtfully.

‘Where does she live?’

‘Somewhere in the north-west of the city. She wrote down her address.’ Margaret pushed a dirty piece of paper across the table. ‘Her family came to Beijing from Shaanxi Province about five years ago. A place called Chenjiayuan, on the Loëss Plateau.’

Li nodded. He had heard of the Loëss Plateau, a dense labyrinth of eroding canyons along the Yellow River. A remote and arid place, where some villages were still unreachable by road. Anyone who could, left. Many of them came to the Chinese capital in search of work, sharing homes at first with friends or relatives who had preceded them, before finding somewhere to stay themselves. Beijing was increasingly dividing into small, distinct communities, tiny ghettos that shared the same rural and provincial heritage.

‘Her father recently lost his job. Their only income is what the mother makes cleaning at the kindergarten. The girl’s been gone almost a week, Li Yan.’

Читать дальше