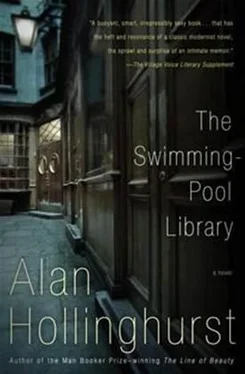

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

When I got back to the flat I was half expecting Phil to be there, and remembered as I slouched sulkily and randily around the kitchen taking a glass of Scotch in great hot nips that he had arranged a couple of nights ‘off’ to see some South African friends, and, tomorrow, to go to a leaving party at the ‘Embassy’. In the sitting-room, remote control in hand, I tripped from channel to channel on the TV, trying to find something attractive in the personnel of various sitcoms and panel games. Abandoning that forlorn pursuit, I put on the beginning of Act Three of Siegfried and conducted it wildly, with great tuggings at the cellos and stabbings at the horns, but without, after five minutes or so, having made myself feel the faintest interest in it. It was in a reluctant mood that I finally settled down at my writing-desk to read Charles’s precious document. When I untied it I found it to be, unlike anything else of his I had seen, an elegant fair copy, from which a compositor could easily have set type.

Although it would have been allowed, I did not keep a journal over those six months. From the start I saw that what I wanted to say, although ‘hereafter, in a better world than this’ it might find other readers and do its good, would have brought nothing but scorn and salacity at the time. And later, long after the start, when I thought writing might earn some slight remission of my solitude and pent-up thoughts, I shunned it, mistrusted it like one of those friends to whom one is drawn and drawn again and yet each time comes away cheapened, wasted or over-indulged. My journal has always, since my childhood, been my close, silent and retentive friend, so close that when I lied to it I suffered inwardly from its mute reproach. Now, though, it seemed to hold out the invitation to something shameful-self-pity, and, worse, the exposure of my narrow, treadmill circuit of memories and longings.

There was too my catastrophic change of station. I had fallen, and though my fall was brought about by a conspiracy, by a calculated spasm of malevolence, its effect on me at first was like that of some terrible physical accident, after which no ordinary thoughtless action could be the same again. The fall had its beginning in that very fast, dazed and escorted plunge from the dock after the sentence had been given, down and down the stone stairs from the courtroom to the cells. I had the illusion-so active is the faculty of metaphor at moments of crisis-of being flung, chained, into water: of a need to hold my breath. In a sense I kept on holding it for half a year.

Chaps did keep journals there-little Joe his childlike weekly jottings for his wife eventually to see, ‘Barmy’ Barnes his notebooks of visions and apocalypses-but they were licensed by their childishness and barminess; whereas I had been violently removed from my rightful lettered habitat, and as an invisible and inner protest refused to write a syllable. Now that I am home again I may write a few pages, merely to attest to what happened-and perhaps to feel my way towards recovery, to patch up my for ever damaged understanding with the world.

One thing I notice already is that since leaving prison I have had long and logical dreams of being back in it, just as when I was in it I dreamt insistently and raptly of happy days long before and also of a day-now, as it might be-when I had been released, and various longed-for things would happen, or promise to happen. Dreams had a powerful and sapping hold on me there. I am the sort of sleeper who has always dreamt richly, so perhaps I should have been prepared for the futile mornings, sewing mail-bags, filling infinite time with that cruel simulacrum of work, but whelmed under in the world of last night’s voyagings, their mood of ripeness and reciprocation. These-and other waking wishes-had such supremacy over the prison’s abstract, cretinous routines that to tell the story of those months with any truthfulness would be to talk of dreams. When, after evening Association-at some infantile early hour-we were sent to our cells, I gained a kind of confidence from the certainty that another world was waiting, a certainty, if you like, of uncertainty, the only part of my life whose goings-on were subject to nobody’s control. The prisoner dreams of freedom: to dream is to be free.

Perhaps the strangest dream I had was one which recalled the evening of my arrest. The frequency with which it recurred could of course be explained by the frequency with which I anyway dwelt on those few crucial minutes. What puzzled me was the variations on the actual events. Always the sequence began with my leaving a group of friends and walking off briskly and excitedly, as I had done, towards the cottage. Which cottage it was, however, altered from night to night, much as it did, of course, in my actual routine. Sometimes I would make for the merry little Yorkshire Stingo, sometimes for the more dangerous shadowy dankness of Hill Place. Sometimes I would find myself going out to Hammersmith, intent on one of those picaresque ‘Lyric’ evenings; and this involved a cab, or bus or train, inevitably subject to diversions, wilful misunderstandings by the driver, or bodies on the line. Even if I was only walking a few hundred yards to a spot in Soho or that ever-fruitful market-barrow, the Down Street Station Gents, I was liable to lose my way or to be caught up in other business, other people’s demands, which only served to increase the frustrated urgency of my quest. Often I would arrive at the correct location to find that the cottage had disappeared, or been closed down and turned into a highly respectable shop. And in reality the places that I sought had in some cases long been closed or demolished. Down Street was shut up before the war; and the station at the British Museum, although I recall no lavatory there, was another imaginary rendezvous, that now is an abandoned Stygian siding; so that my dream dissolved one nostalgia in another, and showed how all closures, all endings, give warning of closures, greater yet, to come.

I enter the narrow, half-dark space-again certain that there will be something for me there, but always uncertain what. In the dream it is only the acrid, medicinal scent that is missing-but the excitement from which it is almost indistinguishable survives. It is a smell as remote as can be from supposedly aphrodisiac perfumes, but its effect on me is electrifying. I unbutton at once, or in the dream remove most or even all of my clothes; my mood is optimistic and youthful-and my body too puts off half a lifetime of weight and care.

After a few moments a handsome young man comes in, his eyes obscured by the brim of his hat; or the lightbulb in its wire cage is behind him, so that he is a figure of promising darkness. I realise that of course I had seen him in the street on my way here, and had had the impression that he returned my glance. He must have followed me in.

He stands well back from the wall and the gutter as he eases his bladder, his penis is preternaturally visible and his attitude encourages me to look at it. Sometimes he seems to drop his trousers round his knees or to undo a wide fly with buttons up both sides, like a sailor’s. In the light of day I can discern elements of many people in him, some of whom he may for a few seconds become, so that I whisper in welcome ‘O Timmy’ or ‘O Robert’ or ‘Stanley!’ At each moment he embodies a conviction of happiness, of a danger overcome. His penis is not quite that of any of the ghosts of whom he is compounded: it is not either large or small, thick or thin, pale or dark, but has an ideal quality, startling me like some work of art which, seen for the first time, outwits thought and senses and strikes in an instant at the heart.

He puts his arms around my neck, and I lick his face and push back his hat, squashing it down urchin-like on his springy black curls. His features are serious and beautiful with lust. We two-step backwards into what is no longer simply the cottage but a light-filled space whose walls alter or roll away like ingenious stage machinery in a transformation scene. We make love in the drying-room at Winchester, or in a white-tiled institutional bathroom, or the white house at Talodi, bare of my scraps of furniture and revealed in all its harmonious vacancy: simple places whose very emptiness prompts desire. In one version we are in a beach shelter of poles and canvas-the sides, luminous as screens of shadow-plays, thrum in the wind, while overhead tiny white clouds are blown across the radiant blue.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.