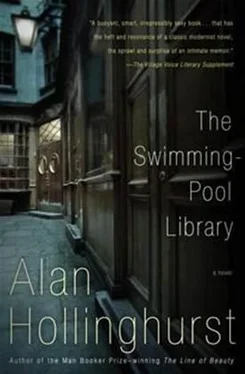

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Charles was looking at it too, and repeated the name, but stressing it differently. ‘Yes, yes, that’s him,’ he said, with a sad breeziness.

‘He’s very beautiful,’ I said honestly.

‘Yes. It’s not an especially good likeness. Sandy Labouchère did it soon after we got back from Africa-you can see he had a rather brilliant line when he wanted to. But he hasn’t brought out the child’s gaiety, a kind of radiance… He was the most beautiful thing on earth. You just wanted to look at him and look at him.’

‘Is he still alive?’ I asked, unable to imagine him going the way of the grocer’s boy into banal middle age; but Charles muttered ‘No, no,’ unanswerably, and then bashed on: ‘So you’ve read all the books I gave you.’

‘Yes, I have. Well, I haven’t read every word, but I’ve taken a pretty fair sample.’ He nodded reasonably. ‘I would read them really thoroughly, of course, if I decided to take on this… job.’

Charles was quite quick and tactical. ‘Quite so, quite so,’ he said. ‘But tell me, I don’t know what sort of impression those books give. Do they appeal at all to, to a younger person?’

‘Oh, I think they’re very interesting indeed. And you’ve done so much,’ I obviously went on, ‘and known such extraordinary people.’

He sighed heavily at this. ‘I ought to have been able to make something of it myself; but it’s too late now. As you get near the end of your life you realise you’ve wasted nearly all of it.’

‘But that’s not the impression I have at all. I’m sure you don’t really think that,’ I said, in the way that one blandly comforts those whose torments one cannot imagine. ‘I mean, I really am wasting my life, and it’s not like what you were doing.’

Charles took this up directly. ‘I’ve no time for idleness,’ he said. ‘I want you to have a job.’

‘I just don’t want the wrong one,’ I said, sounding spoilt even to myself. ‘I’d like it if I could simply disappear, like you did. It was wonderful how you could disappear into Africa.’

‘One disappeared,’ Charles admitted. ‘But one also remained in view.’

I came back to it carefully, weighing the weightless teacup and saucer in my hands. ‘What I rather got the impression of is that you were lost in a dream. It’s very beautiful that feeling the diaries give of a constant kind of transport when you were in the Sudan. It’s like a life set to music,’ I said, in a fantastic impromptu, which Charles ignored.

‘We were doing a job, of course. It was exceedingly hard work: relentless and exhausting.’

‘Oh, I know.’

‘But you’re right in a way-of me, at any rate. It was a vocation. Not all of them in the Service saw it in quite the same light as I did, perhaps. Many of them hardened. Many of them were dryish sticks long before they reached the desert. They write books about it, even now-fantastically boring.’ Charles shot out his foot and sent a book across the hearth-rug to me. It was the memoirs of Sir Leslie Harrap, privately printed and inscribed to Charles: ‘With best wishes, L. H.’. A photograph of the author, in puzzled superannuation, took up the back of the dust-jacket.

‘He was one of the people who went out with you, wasn’t he?’

‘He was a good administrator, loyal, fair, stayed on longer than me, went back in fifty-six to help with the independence arrangements: utterly sound-Eton, Magdalen. Not a breath of imagination in his body. It was reading his book-what’s it called? A Life in Service -that made me realise I didn’t want to write anything of that kind. There is a book in my life, but it’s almost entirely to do with imagination and all that. The facts, my sweet William, are as nothing.’

I looked on abashed. ‘You have published something about the Sudan though?’

‘Oh-yes, I did a little book in the war; part of a series that Duckworth brought out on various different countries, I can’t quite remember why. It wasn’t much good. Fortunately almost all the stock was destroyed when a bomb hit the warehouse. It’s probably worth a fortune now.’ He laughed hollowly; and then lapsed into a vacant half-smile. I was trying to decide whether or not he was looking at me, whether this lull was an enigmatic path of our intercourse or merely one of Charles’s unsignalled abstentions, a mental treading water, ‘blanking’ as he called it. I thought, not for the first time, how odd it was to know so much about someone I didn’t know. A person could only reveal himself as Charles had done to me in love or from a deliberate distance. For half a minute, as I took in his heavy frame, the eyes dark and somnolent in his pink, slightly sunburned head, either reading seemed possible.

‘If you’ve looked at the diaries for when I first went out,’ he said, ‘then you’ll understand how young and aspiring we were. We were quite sophisticated in a way, but with that kind of sophistication which only throws into relief one’s childlike ignorance. It was a bizarre system, when you think about it. There was one of the vastest countries in the world, and they sent out to govern it a handful of boys each year who had never in their brief lives experienced anything even remotely comparable. It wasn’t like India, of course, there wasn’t the same element of domination-indeed, the whole enterprise was utterly different. Anyone could go to India, but for the Sudan there was this careful selection, screening don’t they call it nowadays. They got some worthy Leslie Harrap types of course, and plenty of sprinters and blues to keep things running on time, and they also got their share of cranks and unconventional fellows. There were possibly more of the latter. It was an absurd system and yet very, very subtle, I’ve come to believe. It singled out men who would give themselves.’

‘They didn’t make objections to people’s-private lives?’ I carefully queried, reaching across with the teapot.

‘Thank you, my dear. No, no, no. On the gay thing’ (he unselfconsciously brought it out, seizing a lot of sugar again) ‘they were completely untroubled-even to the extent of having a slight preference for it, in my opinion. Quite unlike all this modern nonsense about how we’re security risks and what-have-you. They had the wit to see that we were prone to immense idealism and dedication.’ Charles sipped his tea excitedly. ‘And of course in a Muslim country it was a positive advantage…’ We laughed at this, though the implications were not quite clear.

‘I’m sure you weren’t such innocents as you make out,’ I said. ‘You must have been trained, after all.’

‘We read a book about the sort of crops and stuff, and did a bit of Arabic.’ Charles shrugged. ‘And then they sent us up to the Radcliffe Infirmary to watch the operations. The idea was that if you saw a lot of blood and severed limbs and so on it would prepare you in some mysterious way for the tropics. They’d bring in chaps who’d been run over, or undergrads who’d tried to do themselves in, and we all had a jolly good look. Fascinating, in a way, but of no obvious benefit for a career in the Political Service.’

Charles was in knowingly good form. ‘So you simply followed your instincts much of the time?’

‘Mm-up to a point. There was a tendency to treat Africa as if it were some great big public school-especially in Khartoum. But when you were out in the provinces, and on tour for weeks on end, you really felt you were somewhere else . If you’d had the wrong sort of character you could have gone to the bad, in that vast emptiness, or abused your power. I expect you know about the Bog Barons in the south-truly eccentric fellows who had absolute command, quite out of touch with the rest of the world.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.