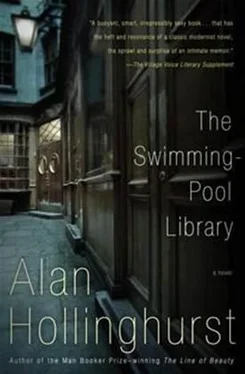

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I was excited by a heavily built man with thick slicked-back hair, and was showing an implausible degree of interest in the picture hanging just by his right shoulder, when the bell went again. We both turned, though he looked away at once while I, seeing Charles shuffle in, felt my mood lighten with friendliness and a flicker of guilt. I had been neglecting the old boy, and seeing him now in this noisy, confusing place recalled my responsibilities. I went to help him.

‘Ah… ah…’, he was saying, looking regretfully to left and right.

‘Charles! It’s William.’

He took my arm at once. ‘I know perfectly well who it is. What an orgy… Good heavens.’ He gave off, close to, the elderly smell of sweat and shaving-soap. ‘We almost didn’t come,’ he admitted, with what I took for humorous grandeur.

‘I’m very glad you did. I haven’t seen you for ages.’

He was prodding his other hand behind him, like someone searching for the armhole of a coat. ‘This is Norman,’ he explained, as another man, thus encouraged, came forward from his shadow. ‘The grocer’s boy.’

Norman reached round Charles to shake my hand. ‘I’m the grocer’s boy,’ he confirmed, very happy, it seemed, to be remembered by his juvenile role. As he was a man in his mid-fifties I found it hard to place him at first. ‘I used to work in the grocer’s in Skinner’s Lane,’ he said, smiling, nodding, ‘years and years ago, when Lord Nantwich first moved in.’

I cottoned on. ‘And then you joined the merchant navy and sailed all over the world.’ He smiled again, as at the successful recitation of an old tale.

‘I left the service some time ago now, though.’ Service, one could see, was something he was proud of, and his whole manner spoke of it. He was soberly dressed, in an ill-fitting grey suit and shiny casual shoes of a kind that had been fashionable in my earliest childhood (my father had worn something very similar on family holidays). The suit, which was broad in the shoulders and stood off the neck, was the sort of thing that students bought in second-hand shops, and on one or two of the modish boys in this room could have had a certain chic. Norman’s wearing of it was without irony and he reminded me, as the man in the lavatory had reminded Charles forty years before, of a College scout, habituated, stunted by service. His face shone.

‘Norman dropped in this afternoon,’ said Charles. ‘Quite amazing. I hadn’t seen him for over thirty years.’

‘I sent him a picture of me from Malaya, though.’

‘Yes, he sent me a picture from Malaya.’

‘I was surprised Lord Nantwich recognised me, even so.’

Charles puffed and muttered something about a tifty. ‘Come and have a drink,’ I said to both of them, and I took Charles’s wrist to lead them through the crowd. I could see, as I swivelled round to pass Norman a glass of wine, that he would always be recognisable. His broad cheekbones, large mouth, grey eyes and blond hair, now indistinctly grey, were elements in a formula of beauty, whatever disappointments and desertions might have taken place. Charles was politely inscrutable, but I sensed that he was pained to be disabused. He turned away from the ‘grocer’s boy’ who had needlessly returned to destroy the sentimental poetry with which he had been invested. I felt sorry for them both. And then, drunk again, hated the past and all going back.

‘I share a house with my sister,’ Norman was explaining to me. ‘It’s very near the middle of Beckenham, quite convenient for the station and the shops.’

‘You should have brought her today,’ said Charles loftily.

Norman flushed at this, and looked around hectically at the straining torsos and ecstatic mouths upon the wall.

‘Can I come and see you soon, Charles?’ I asked. ‘I’ve been picking my way through the books, and I’ve almost got up to the end. I need some briefing.’

‘Briefing, tomorrow?’ His eye had been caught by Staines, and I watched his attention waver and then switch abruptly away. Staines reached a ringed hand to him and I heard Charles saying ‘… splendid evening, most memorable…’

I kept up with him and squeezed his arm: ‘I’ll come for tea, as before’-and he patted my hand. Then I was talking to the thick-set man, laughing overmuch so as to charm, and with my shirt half unbuttoned, running my hand over my chest. He was keen on photography, had his reservations about Staines-I agreed with him brutally-but liked Whitehaven. I told him Whitehaven had photographed me, but I saw that he thought I was taking a rise out of him. ‘Well, have you done any modelling?’ I asked.

Aldo came up and said, ‘Oh, let’s be going.’ He looked tipsy and abandoned. It was only when the three of us were virtually through the door that I realised his words had been addressed to the thick-set man rather than to me.

‘Nice meeting you,’ said the thick-set man; and other perfectly pleasant remarks were exchanged before the two of them strolled away, arm in arm. I lurched off furiously to the hotel.

11

‘Sugar?’

‘I don’t, thank you.’

‘I rather do these days. I’ve given in.’ Charles discarded the tongs, and shovelled up roughly half a dozen sugar-lumps in his bowed, flat fingers. We sat and sipped as Graham came in again with more hot water, and Charles watched his manservant with confident gratitude. At Skinner’s Lane everything was running like clockwork. ‘I have my own teeth,’ he added.

We sat, as before, in the little library, Charles’s den, the only part of the house which did not come under Graham’s orderly care. Each time I visited it there were signs of new disturbances, books moved from table to floor, old Kalamazoo folders stacked or scattered, as if some task of sorting and searching were being executed, leaving only greater confusion, like a site turned over for coins and amulets by amateurs. Books whose titles had caught my eye last time atop their teetering plinths were now cast down or overlaid by other strata: atlases with cracked spines, popular sheet-music (the ‘Valse’ from Love-Fifteen ), magazines whose colour printing had freaked with sun and age and, Gauguin-like, showed brown royalty, pink dogs, pale blue grass.

I felt at home there. As we sat on either side of the empty hearth, I was reminded of my Oxford tutorials, and the sense I often used to have of inadequacy and carelessness in the face of my tutor, whose hours with me, he came to imply, were needless distractions from his own, decades-long work on succession and the law. There was a similar maleness and candour to it, that scholarly inversion of the rules of the drawing-room that allowed one to talk about sodomy and priapism as though one were really talking about something else. There was a similar toleration of silence.

‘Most tiresome,’ Charles enigmatically resumed. ‘One lives in the past fully enough as it is, without people coming back like that.’

‘Your grocer’s boy. Yes, I confess to having been a bit disappointed.’

‘He couldn’t see that he only had meaning in the past, poor fellow.’

‘I think Martyrs were perhaps a bit much for him.’

Charles smiled wistfully. ‘I thought they’d scare him off, but he rather took to them.’

‘I can see that he must have been pretty hot stuff once,’ I conceded. ‘And the shop-boy thing is so glamorous, all the whistling and the boredom, and the way they’re trapped there, on show.’

‘He used to go out on a bicycle,’ Charles corrected my over-warm reconstruction. ‘He did the deliveries with an apron on.’

I lifted the fluted shallow teacup to my lips, and my eyes rose again, as they inevitably did in this room, to the chalk drawing above the fireplace. Taking a risk on it, I said, ‘Is that Taha in that picture?’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.