And yet it was the mood which fascinated. This marionette of a man, on his last legs, had been picked on by the crowd, yet as they mobbed him they seemed somehow to be celebrating him. He became perhaps for a moment, what he must always have wanted to be, an entertainer. The children’s expressions showed that profoundly true, unthinking mixture of cruelty and affection. There was fear in their mockery, yet the figure at the heart of their charivari took on the likeness not only of a clown, but of a patron saint. It was a rough impromptu kind of triumph.

There was a brief tableau in which order had been more or less imposed. The children gathered round Firbank and glared and grinned at the camera; Firbank flapped his hat in his hand and looked hot and bothered. A little girl tugged at his trousers and he pulled his pocket inside-out with a drooping and muffled gesture to say he had no more to give. He smiled too, but showed that he wished it was all over: it was a tiring situation for so childless and singular a man. In the final few seconds he was walking away by himself: there was something decisive and businesslike about him; in spite of everything he was in a hurry, he had work to do. Then a fat boatered man and a woman with a parasol were parading past a tent with the word STEWARD on it. ‘Ah, that’s the end of our film,’ said Staines, and put out the projector’s bulb. We were in virtual darkness for several seconds, and James squeezed my hand and I felt his charge of emotion.

‘It’s the most wonderful thing I’ve ever seen,’ he said, in the way that one does to a host, but he meant it.

‘Quite a find, eh?’ Staines agreed, putting on the light. ‘I want to turn it into a little feature, with a commentary perhaps by you, Mr Brooke, if you would care to.’

‘I’ve got some ideas about it,’ said James.

‘I’ve been to Genzano, of course,’ muttered Charles, who did not want to be left out. ‘They have this festival of flowers, and the main street is carpeted with… er… with flowers.’

‘Very Firbankian,’ I put in my obvious bit.

‘You mean, on another day,’ said James, ‘if it only had been another day, we would have seen the flowers beneath his feet.’

Chatter about this went on, and I asked Staines surreptitiously about the Colin pictures. ‘Oh, I’d forgotten,’ he said, hand raised chidingly to brow. ‘Will I ever be able to find them?’

‘Is it a frightful bore?’ I said courteously. ‘I just thought as I was here, and you had kindly said…’

‘Oh, I know. But there’s no system, as you doubtless recall.’

‘Actually I think I can remember roughly where they were.’

He allowed me to take out the huge print drawer that Phil (ouch!) and I had shuffled through weeks before. ‘You’re welcome to look ,’ said Staines, as if he held out little hope.

But it was the right place. I recognised the Mayfair portraits, the louche studies of Bobby-Bobby who today was nowhere to be seen, banished doubtless under the good behaviour clause-and all the randomness of it was right to me, as that was how it had been before. But when I got to the bottom, and peeled back the last piece of protective tissue, I had to acknowledge that none of the pictures of Colin, those artfully lewd compositions, was there. I searched the drawers above and below as well, but with dwindling hope. Charles called out, ‘What’s he looking for?’ and when Staines replied, ‘I promised him some photographs of a boy called Colin, but I just don’t know where they are,’ I knew he was lying.

‘Colin?’ said Charles. ‘Oh, I don’t think I know that one. Do I know that one?’

I nodded at him to signal that this was the boy I had told him about, the thing that mattered to me; but he was quite inscrutable, full of diplomatic ignorance. Half an hour later, when we shook hands and parted, he wouldn’t meet my eye.

‘Well, that was a mixed success,’ I said to James, as he climbed down into his car, and I leant over the open door.

‘Don’t worry about the Colin thing,’ he said.

I drummed on the roof. ‘I want to get him! I don’t seem to have anything else to do.’

‘Do you want a lift?’

‘No, I’m going home. Then I’m going to have a swim: one must keep the body if not the soul together.’

‘See you soon.’

‘See you my darling.’

It was very quiet at the Corry, when I arrived mid-afternoon. The few people there looked at each other with considerate curiosity rather than rivalry. There was a sense of various different routines equably overlapping. There were several old boys, one or two perhaps even of Charles’s age, and doubtless all with their own story, strange and yet oddly comparable, to tell. And going into the showers I saw a suntanned young lad in pale blue trunks that I rather liked the look of.

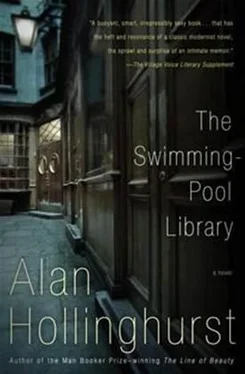

Alan Hollinghurst is the author of three other novels, The Folding Star, The Spell , and The Line of Beauty , which won the Man Booker Prize in 2004. In addition, he has received the Somerset Maugham Award, the E. M. Forster Award of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Fiction. He lives in London.

***