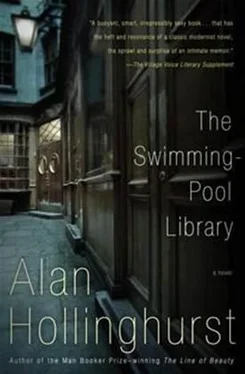

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Bill and I became great friends, and he, who was regarded as a kind of mascot by many of his fellows, and entrusted with secrets in the way that one might pour out one’s feelings to one’s dog or cat, knew a great deal about almost everybody, and seemed to feel keenly their various trials and tragedies. He pointed out to me a number of relationships between the men, confirmed my suspicious interpretations of odd gestures and habits, and revealed what was fairly a structure of submerged bonds and loyalties. There were half a dozen longstanding affairs going on, and various other men and boys were available if properly approached, or shared their favours with a satisfactory polygamy between two or three of their companions. In a way what had happened was a comic reversal of the circumstances which had put us all in there in the first place, with the prison authorities bringing us together, admitting our liaisons, and protecting us from the persecution of the outside world. The screws themselves were by no means indifferent, it transpired, and two of them at least were having sex on a daily ration with prisoners-though those prisoners were treated with the greatest suspicion by their fellows as being probable grasses. One of them was provided with lipstick and other maquillage by his officer, and his femininity, at least, was tolerated as it would not have been outside.

Bill drew me out too, and I have a clear and rather touching picture of him sitting opposite me, his powerful, stocky young frame transforming the stiff grey flannel of his uniform so that he looks like a handsome soldier in some poor, East European army. He concentrates on me closely as I tell him about my childhood, or about life in the Sudan; and he is interested to hear about my house and my servants. I have promised him that when he is released, early next year, I will find him something to do: a job in a gymnasium, if possible, where his feeling for men and physical exercise can be fulfilled, rather than baulked and denied in some clerkly work. It was rather desperate to see him toiling for weeks over detective novels from the prison library: he doggy-paddled through books in a mood of miserable aspiration, but they were not his element.

I took to the prison library with more duck-like promptness. It was a bizarre collection, made up almost entirely of gifts. Ordinary well-wishers and a number of voluntary bodies gave miscellaneous fiction and popular encyclopaedic works on technology and natural history; an outgoing governor had presented a collection of literary texts, some deriving from his own schooldays but also including French classical drama and the complete works of Wither in twenty-three volumes; and the Times Literary Supplement had charitably for some years sent to the prison all those books it felt no interest in reviewing, a body of work ranging from bacteriology to handbooks on historic trams.

I picked on something which must have come from the ex-governor’s bequest: a schools edition of Pope, with notes by A. M. Niven, MA-one of those frustrating near-palindromes with which life is strewn. It had seen active service, and words such as ‘zeugma’ filled the margins in a round, childish script. I had not read Pope since I was a child myself, but I had a sudden keen yearning for his order and lucidity, which was connected in my mind with a vision of eighteenth-century England, and rides cut through woodland, and Polesden and all my literate country origins. The book contained the ‘Epistle to a Lady’ and various other shorter poems; of the longer works it gave only ‘The Rape of the Lock’ complete, and I fastened on this poem, and on Mr Niven’s account of how it had been designed to laugh two families out of a feud, as the flashings and gleams of a civilised world, where animosities were melted down and cast again as glittering artefacts. I determined to learn it all by heart, and put away twenty lines a day. The discipline, and the brilliance of the work itself, were a kind of invisible enrichment to me-though, lest I should feel like an actor learning a great part with no prospect of a performance, I had Bill hear my lines each time I mastered a new canto; and he seemed to enjoy it.

Tempting though it was to retire into this inner world, there were always visits to look forward to-and to regret, for their cruel brevity and for the new firmness with which, afterwards, the door was shut, the walls of the cell confined one. The visitors carried their horror of the place about them and for a while after they had gone left one with an anguished vacancy of a kind I had never known before. All one’s little accommodations were laid bare.

My first visit was from Taha-a ‘box-visit’, a reunion conducted through glass. I was wildly shaken to see him, so that I could not think of much to say. He smiled and was solicitous, and I looked at him closely, masochistically, for signs that he was ashamed of me. It was extraordinary how his confidence was undimmed: he spoke very quietly, so as not to be overheard by the guards or the other prisoners, and told me a score of sweet, inconsequential things. The second time he came, a few weeks later, we were allowed to sit at a table together: he had his little boy with him now, who seemed very excited at being allowed into a prison but frightened too of being left behind. Taha told him to hang on tight to my hand, and as he himself was holding my other hand we sat linked in a triangle, as if conducting a seance. The day before had been Taha’s birthday-and of course I had nothing to give him. He was forty-four! I can honestly say that he was no less beautiful to me than he had been when I saw him first, twenty-eight years ago. His brow was higher, his face scored with lines that had been mere charcoal strokes on the boy’s velvety brow and cheeks. His eyes, though, had deepened their immensity of melancholy and laughter, and his exquisite hands too were lined and shiny as old leather, as if he had done far more than merely polishing my shoes and silver.

That night I lay long awake, caught up again, with a vividness of recall, in the life we had spent together. Despite a thousand differences it was like a marriage, a great, chaste bond of love and tact-which made it all the odder that he had really married and become a father. I was gripped again by my mood of awful falseness and despair on his wedding day, when I gave him away into that little house in North Kensington and into a world more unknown and inaccessible than the Nuba Hills where I had found him first. Since then I have seen this period simply as a test, challenging our bond only to affirm it again. The terms were different, his independence, as each evening he went off on the Central Line, took a concrete, dignified form; but his loyalty was unaltered. Perhaps his distancing even endeared him to me more, and showed me afresh a devotion to which we had both become over-accustomed.

Such thoughts were still uppermost in my mind when I was called to see the governor a couple of days later. We had not met since the cursory talking-to of my first day, an occasion when I was strongly aware of the unease that his brief and accidental superiority had given him. Dressed though I was in my deforming prison bags I was made to feel wickedly sophisticated. He knew the disadvantage I suffered under would not-even should not-last. Today he was absent, and one of the senior officers took his place, pacing behind the desk but starchily resisting the temptation to sit down. I was not asked to sit myself, and as I refused to stand to attention, I adopted a rather decadent kind of slouch, which the officer did not like, visibly suppressing his criticism. I wondered what was up and had faint expectations of some kind of remission.

‘I have some’-he seemed to hesitate to choose and then reject an adjective-‘news for you, Nantwich. You have a servant, a houseboy. What is his name?’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.