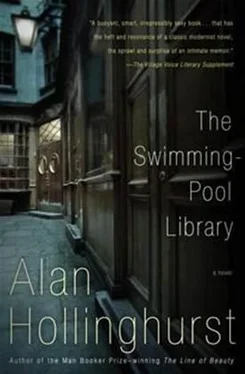

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘I have a companion. He is called Taha al-Azhari.’ I spoke with assumed calm, suddenly afraid that Taha had done something stupid, something he thought would help me.

‘Azhari, exactly. He came from the Sudan, I believe?’

‘Yes.’

‘How old a man?’

‘He is just forty-four.’

‘Wife and children?’

‘I really don’t see the point of this. Yes, he has a wife and a seven-year-old boy. I think you saw the boy yourself,’ I added, ‘when he came to visit me last week, and Taha himself of course…’

The officer showed no recollection. ‘Azhari will not be coming to visit you again,’ he said. I shrugged, not out of carelessness, but out of a refusal to show care, and in a mute lack of surprise that to my current deprivations others were to be added.

‘Have I done something wrong?’ I suggested. ‘Or perhaps he has?’

‘He’s dead,’ said the officer, in a tone overwhelmingly vibrant and severe, as if this event were indeed a proper part of my punishment and as if to Taha too some kind of justice had at last been done.

‘I confess,’ I said, ‘I am surprised you should find it fitting to convey such news, even such news, in the form of an interrogation.’ I stepped with a kind of blind resolve from word to word, and it was only my utter determination to deprive him of the sight of my agony that kept me pressing on. He said nothing. ‘Perhaps you will tell me how this happened. Where did it happen?’

‘I gather he was set on by a gang of youths, over Barons Court way. It was late at night. I’m afraid they showed no mercy: stones and dustbins were used as well as knives.’

‘Is any… motive known?’

‘I wouldn’t know. The police have no idea of course who did it. It seems not to have been for money-he still had money on him. Did he usually carry money?’

I ignored the lazily loaded question. ‘There can be no doubt that this was an act of racial hatred and ignorance.’

‘I’m afraid so, Nantwich. I think there will be more of them, too.’ He looked confident of vindication, almost proud. I was still standing in the middle of the room, though by now I was beginning to shake, and had to force my knees back and grip my hands together.

‘Your opinion is of no interest to me,’ I said.

He gave a little smirk. ‘You will be allowed to attend the funeral,’ he said, as if I had been wrong to judge him so harshly.

And so the light of my life went out.

The morning of the funeral was ragged and squally, and I was stunned to find how readily I returned to the Scrubs and hid myself away: even if a car had been waiting to drive me home I would have been incapable of accepting it-and throughout the first few days of choking grief the hermit bleakness of my cell served to contain me in the fullest sense. In my own house I would have fallen apart. The other men, my friends, too, helped me and held me, and showed in their laconic condolences an understanding I could never have received in the world at large.

It would be unedifying to describe as it would be needless torture to recall those days when the world first changed, and became a world without my Taha. It was a terrible destitution, and my knowledge is all bound up with my physical experience of the hard coir mattress where I lay, the few properties of my cell, the bladeless razor, the little framed square of looking-glass in which I caught my tear-blotched face, the steady night-time smell of the chamberpot. As the autumn drew on it grew colder in the prison, but if one held one’s hand to the black iron vent through which warm air was supposed to issue into each cell one felt only a slight chill stirring, which seemed to come from far away.

It was a time of incessantly recurrent images of my sweet dead friend, and of a thousand memories fanned into the air by this cold draught. I haunted and interrogated the past even as it interrogated me. London, Skinner’s Lane, Brook Street, the Sudan-how had we passed all that time? Why did we not burn up every moment of it, as we would if we could have it all again? The journey back to England surfaced in dreams and occupied my days, the train to Wadi Halfa panting across the desert, reading old newspapers in the white, shuttered carriages while Taha, alas, was obliged to travel with the guard; and the stops, which had no names, but only a number, painted on a little shelter beside the track; and the steamer to the First Cataract and the visionary beauty of Aswan.

And I went further back, prone and defenceless, to Oxford and Winchester, shrinking from the world, curling up in the warm leaf-mould of earlier and earlier times, drawing some wan, nostalgic sustenance from those dead days. My life seemed to go into reverse, and for a month, two months, I was a thing of shadows. It was in vain to tell myself that this was not my way: I was impotent with misery and deprivation.

Then, as the end came in sight-it was the dead of winter-something hardened in me. I saw the imaginary verdure beyond the frosted glass. I began to think of the world I must go back to, with its brutal hurry and indifference. I would have to take on a new man. I would have to move again in the company of my captors and humiliators and be glanced at critically for signs of the scars they had inflicted. I would have to do something for others like myself, and for those more defenceless still. I would have to abandon this mortal introspection and instead steel myself. I would even have to hate a little.

I see in The Times today that Sir Denis Beckwith, following calls in the House for the reform of sexual offence law, is to leave the DPP’s office and take a peerage. Oddly typical of the British way of getting rid of troublemakers by moving them up-implying as it does too some reward for the appalling things he has done. Perhaps I will have the opportunity to argue with him over law reform in the House-perhaps the only occasion in Hansard when a Noble Lord will have challenged another such who more or less sent him to prison. And he is a man I could hate, the one who more than anybody has been the inspiration of this ‘purge’ as he calls it, this crusade to eradicate male vice. Though one always treated him with contempt, he will now be a powerful voice in the Lords, with others like Winterton and Ammon-though beside their ninnyish rant he will be the more powerful in his cultured, bureaucratic smoothness. I have the image of him before me now in the courtroom at my sentencing, to which he had come out of pure vindictiveness, and of his handsome suaveté in the gallery, his flush and thrill of pride as I went down…

It was Graham who answered the phone. ‘Oh Graham, it’s Will Beckwith-is Lord Nantwich there?’

‘I’m sorry, sir, he’s dining at his Club this evening.’

‘At Wicks’s? When will he be back?’

‘I don’t expect him until late, sir.’

‘I’ll try again tomorrow.’

But tomorrow was too far away. I was so confused by this digest of disasters, I felt so stupid and so ashamed that I walked around the flat talking out loud, getting up and sitting down, scratching my crew-cut head as if I had lice. It was impossible so quickly to formulate a plan, but I felt the important thing was to go to Charles, to say something or other to him.

It took me ages to get a cab, and as at last it locked and braked its way through the West End closing-time crowds, I found all my ideas of what I might do rattling away, leaving me in a queer empty panic. I left the cab in a jam a block from the Club and ran along the pavement and up the steps. The porter emerged from his cabin with an expression of moody servility and told me Charles had left quarter of an hour before. I hardly thanked him, but dawdled out again, realising that at this moment he was probably roaring along the Central Line on his way home. I drifted around in front of the Club as if waiting for somebody, hands in jacket-pockets, chewing my lip.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.