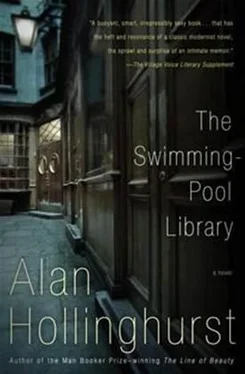

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In another version, of course, it is not like this. I enter the lavatory and within a few seconds hear the click of metal-tipped shoes approaching the doorway, and look casually across at the young man who takes his place next to me. He is so gorgeously beautiful, in American jeans and a flying-jacket, that I can hardly believe, as he vigorously shakes his prick and with his other hand pushes back his lustrous hair, that his act is aimed at me, a man of twice his age, an old gent in an old Gents. In a cottage one takes what one is given, and is thankful; but nonetheless I am fifty-four-I hesitate before such golden opportunities. I am looking down intently, paying no attention, though my heart is racing, and then I hear other footsteps outside. I have missed my chance. But oddly the footsteps stop, recede, and then after a few seconds start back again. Somebody is waiting there. I glance quickly at the young man and his thick erection, and find he is looking at me steadily. I take a deep breath, and my heart sinks like a stone as I realise I am about to be robbed, more, perhaps badly beaten. If I try to leave I will be caught between the lovely boy-whom I see now for what he is, a steely young thug, perhaps the very one there has been talk of lately in the pubs-and his companion nervily keeping watch outside.

It is a horrifying moment, and I button up hastily and step back, all my instinct being to preserve myself as far as possible from the physical and moral outrage which almost visibly gathers itself to strike. There is a thumping silence, and the light of the one lamp across the wet tiled floor seems conscious that it will illuminate this and many other atrocities, just as it will go on shining through days and months of sudden speechless lusts, and all the intervening hours of silent emptiness. The boy, seeing I have begun to escape, himself adjusts his dress, but says nothing to me. As I go out at an ungainly scuttle he is behind me, almost beside me, and I see the other man, in a dark overcoat, step forward and look interrogatively past me. The boy lets out a little affirmative grunt, the man raises his hand to my lapel and speaks: ‘Excuse me, sir…’ but I am slipping past him, dreading to become involved in their insults and sarcasms. It is only a second later when I hear a car approaching and make for the opening in the bushes, beginning or meaning to cry out, that I slam full length to the ground, my arm is jerked behind my back, the boy is astride over me, and the man in the coat says: ‘We are police officers. You are under arrest.’

My months in the Scrubs were a kind of desert in time: beyond their strict and ascetic routines they were featureless, and it is hard in retrospect to know what one did on any day or even in any month. I had had, of course, some experience of deserts, even a taste for them, and knew how to fall back, like a camel on its fat, on an inner reserve of fantasy and contemplation. I was a kind of ruminant there. Even so, it did not turn out in quite the way that-in the first numbed and degraded hours-I had imagined it would. Indeed, for several weeks the time rushed by, and it was really only in the final month, when freedom grew palpably close, that every minute took on a crabwise, cunctatory manner, came near to stalling altogether. I was haunted then by an image, a visionary impression of young spring greenery-birches and aspens-quickened by breeze but seen as if through frosted glass, blurred and silent. But by then a real atrocity had happened, something more than my freedom had been taken away from me.

My early days there called on my resilience. It was like being pitched again into the Gothic and arcane world of school, learning again to absorb or deflect the vengeful energies which governed it. But a difference soon emerged, for while the schoolboys were bound to struggle for supremacy, and in doing so to align themselves with authority, thus becoming educated and socially orthodox at once, we in the prison were joined by our unorthodoxy: we were all social outcasts. The effects of this were often ambiguous. Many of the distinctions of the outside world survived: respect for class, disgust at certain violent or inhumane crimes, and the ostracising of those who had been convicted of them. But at the same time, since we were all criminals, a layer of social pretence had been removed. There could be no question of pretending one was not a lover of men; and since many of the inmates of my wing were sex criminals-or ‘nonces’ in the nonce-word of the place-there was between us a curiously sustaining mood of sympathy and understanding. Of course guilt and shame were not magically annulled by this, but a goodish number of us-by no means all first offenders-had been caught for soliciting or conspiring to perform indecent acts, or for some intimacy (often fervently reciprocated) with underage boys. And many of the prisoners themselves, of course, were little more than children, old enough only to know the dictates of their hearts and to be sent to prison. The place was fuller than it ever had been with our people, as a direct result of the current brutal purges, and many were the tales of treachery and deceit, of bribed and lying witnesses, and false friends turning Queen’s Evidence, and going free. Such tales circulated constantly among us-and I added my own mite to this worn and speaking currency.

My case, on account I suppose of my title, had been the subject of more talk than most-though nothing like as much as that of Lord Montagu, which shows all the signs of iniquity and hypocrisy evident in the handling of my arrest and prosecution, but wickedly aggravated by police corruption. In the prison my fellows felt sure that we two must be acquainted, and imagined us, I think, swopping young men’s phone numbers in the bar of the House of Lords. It was hard to convince them that not all peers-just as not all queers-know each other. Even so it appears that his case-and in its little way mine-are doing some good: even the decorous British, with their distrust of the life of instinct, their pleasure in conformity, are saying that enough is enough. Some of them, even, are saying that a man’s private life is his own affair, and that the law must be changed.

My dim lavatorial notoriety became in the prison a kind of glamour, and helped me, as I looked about and learnt the faces and moods of the men, to make friends. Covert gestures of kindness saved me from trouble, or explained the punctilio of some futile but unavoidable chore. Matchboxes and half-cigarettes were slipped to me as we jostled together for Association. Warnings were given of the foibles of particular screws. And so the nonce-world, which became my world, closed about me, offered me its pitiful comforts, and began to reveal its depths-now murky, now surprisingly coralline and clear.

My guide and companion in this was a young man I met after a week or so, a well set-up, rather tongue-tied little chap called Bill Hawkins. I had noticed him early on, and was not surprised to find that he spent a lot of time in the gym: he had a fine torso and packed shoulders. We played a few games of draughts together on my first Sunday evening. He clearly wanted to talk to me, but was uncertain how to go about it, so I drew him out. It transpired that he had been for over a year the lover of a teenage boy who trained at the sports club in Highbury where Bill was employed. They saw each other every day, and were blissfully happy, though Alec, as the boy was called, avoided his old friends and caused concern to his parents by his singular behaviour. Twice Bill and Alec went to Brighton and spent the weekend in a guesthouse owned by a friend of the sports club manager: if anyone asked questions they were to pretend to be brothers, for Bill himself was only eighteen, and Alec was a couple of years younger. After a while, though, Alec became more distant, and it soon became clear that he was involved with another man. Bill, in all the torments of first love, took precipitately to drink, and would make a nuisance of himself banging on the door of Alec’s parents’ house. Then foolish, intimate letters were written: and found, by the parents. They showed them to Alec’s new friend, an insurance salesman with a Riley whom they, in a fine hypocritical fashion, considered more suitable and respectable than poor, passionate, uncontrollable Bill. Together the salesman and the parents took the letters to the police. Bill, when questioned, did nothing to conceal his feelings. He was sent down for eighteen months with hard labour.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.