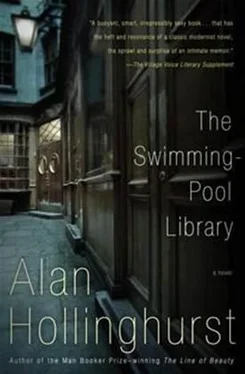

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘But darling, I was going to give it to you.’

James was terribly upset about the book. ‘I haven’t got one with the wrapper. It was probably worth £100-more, if it was as mint as you say.’ He sat beside me on the sofa, holding my hand. It was rather awful to see him so cheated of his treasure, his aghast look of cupidity and disbelief.

‘I’m afraid the dustmen will have cleared it away by now.’ I spoke thickly, as though I were very drunk. By a miracle I had only lost one tooth, but as it was right in the front it gave me the fatuous air of a defaced advertisement. My left cheek was purple, my mouth swollen and lopsided, and my left eye narrowed to a gluey slit in a bed of tenderest black, like an exposed mollusc. Over the bridge of my beautiful nose, broken and cut, an apache stripe of dressing was stuck.

My James was so movingly practical over all this, not repelled, even slightly in his element, somehow vindicated. Deliberately or not, he kept making me laugh, which I could hardly bear, with my bludgeoned head, cracked ribs, and the bruises and contusions on my side and my legs. I had always had such good health-never a broken bone, never a filling, all the household ailments checked off in childhood-that James had had no occasion to prescribe to me for more than a hangover. Because we were always so private with each other he seemed almost to be play-acting when he sounded me and felt me expertly with his still mottled, childish hands, and took my pulse and gave me tiny, painkilling pills. I surrendered to his doctoring, since it resembled the special kindnesses and attentions of an intimate, done for our mutual pleasure. At the same time I knew he was judging me physically and professionally, despite his look of doleful pride at having such a dangerous friend.

Phil came too, each afternoon, fresh from his lunchtime breakfast. Though still hot, the weather had turned rainy and bothersome, and he wore a blue showerproof jacket with a hood. He would look lightly flushed when he came in and took it off, and he concealed his initial dismay at my appearance with a preoccupied, evasive manner. For ten days or so I hardly went out and he sweetly brought me food-tinned soups, fruit juice, bread and milk-which he unpacked on the kitchen table for me to see. But I didn’t have much appetite. His catering, out of a baffled desire to make everything better, was over-generous, and I twice found myself throwing bread away-guilty about it as I never would be about throwing out overripe fruit, an unpicked carcass of partridge or grouse.

Despite the pleasant passivity of being a patient, a condition ministered to as by some perverse kind of luxury, I was profoundly shocked by what had happened. I was constantly reliving the sudden sickening panic of it. James gave me things to help me sleep, which left me drowsy and dozing through the morning, running in and out of horrible, sour little dreams. I hated it when Phil had to leave for work, and longed for him to arrive the following day.

James felt that my mother at least should be told, but I was fiercely against it. She was due in town shortly to restock the deep freeze with exquiseria unavailable in Hampshire, and to buy new clothes to fit her ever-expanding figure. When she rang to fix the routine lunch in Harrods (it had to be on the spot so as to minimise the loss of spending time) I told her I would be going to stay with Johnny Carver in Scotland that week-though in fact I had not seen Johnny since the day of his crassly youthful wedding two years before. My mother said I sounded odd, and I said I had just come from the dentist-a lie nearer to the truth.

It took something of an effort to look at myself in the mirror which usually gave me such quick, uncomplicated pleasure. As I stood washing my face with extreme gentleness, even the fronds of the sponge seeming rough on my puffed and tender skin, I found it took that kind of mastery to meet my eye in the shaving-mirror that I had needed, as a child, to look at certain pictures not manifestly horrible in themselves but subtly repulsive or awesome through some accretion of mood. My grandfather had at Marden a portrait of his aunt, Lady Sybil Gossett, by Glyn Philpot. It showed an ivory-faced society woman, of the kind perplexingly referred to as ‘a famous beauty’, with bobbed fair hair and large, lugubrious eyes. She wore a misty pale blue frock, cut very low at the bosom, and sat back in a little chair beside a tub of mauve hyacinths. Her melancholy, so intense it seemed almost depraved, and the vulgar sensuality of the colour scheme, were deeply terrible to me as a child, and I could not bear being alone in the dining-room where she hung. It was a family joke that I was ‘snubbing Sybil’ by having always to eat with my back to her, and I was not unpleased to be the victim of so abnormal and aesthetic an emotion. At times I would steel myself and look. It was just like now, keeping my eyes fixed there until the spirit-lamp of rationality guttered, my gaze flicked away in fear.

James had said humorously that I wouldn’t like having my beauty spoiled, and though it could all be remedied I found my injured appearance unbearable. My vanity, which was so constitutional that it had virtually ceased to be vanity, was shown up for what it was; I bit Phil’s head off when he blandly suggested that I didn’t look too bad. For a while I became the sort of person that someone like me would never look at.

After a few days I took a turn around the block with Phil. Accustomed to daily exercise, I now experienced an aching restlessness which mingled with the pain of my bruises and bones. I couldn’t make my limbs comfortable, and had to get out. It was a bright, blowy tea-time. Already people were coming home, the traffic was building up at the lights. The pavements were normal, the passers-by had preoccupied, harmless expressions. Yet to me it was a glaring world, treacherous with lurking alarm. A universal violence had been disclosed to me, and I saw it everywhere-in the sudden scatter across the pavement of some quite small boys, in the brief mocking notice of me taken by a couple of telephone engineers in a parked van, in the dark glasses and cigarette-browned fingers of a man-German? Dutch?-who stopped us to ask directions. I understood for the first time the vulnerability of the old, unfortified by good luck or inexperience. The air was full of screams-the screams of children’s games which no one mistakes for real screams as they blow on the wind from street to street. If there were real screams, I found myself wondering, would it be possible to tell the difference, would anyone detect the timbre of tragedy? Or could an atrocity take place whose sonority was indistinguishable from the make-believe of youngsters, their boredom and scares? I had never screamed in my life. Even when the three boys had laid into me I had uttered only formal little oaths, ‘Christ’, ‘God’ and ‘Oh no’.

There was a lot of time to fill, but I hardly did anything useful. Mainly I closed the curtains and watched Wimbledon, alternately alerted by a breathtaking rally and soothed by the drowsy putterings of Dan Maskell, like some rich stew left bubbling all day long over a low flame. James brought me videos from the rental shop, as well-not the bath-house freak-shows he usually offered, but charming old films to make me feel better. On his day off-which was drizzly, the covers were on at the Centre Court-we sat and watched The Importance of Being Earnest together. Michael Redgrave and Michael Denison were such bliss, so brittle and yet resilient, so utterly groomed and frivolous, dancing about whistling ‘La donna è mobile’… Afterwards James told me his theory about Bunbury and burying buns, and how earnest was a codeword for gay, and it was really The Importance of Being Uranist. I had heard it all before, but I could never quite remember it.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.