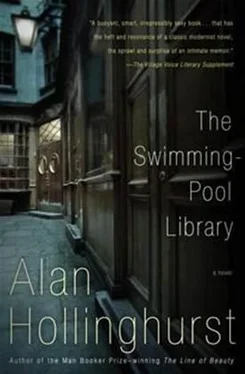

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘What have you found there?’ said Charles, with a hint of possessiveness in his voice. I handed him the envelope with some excitement. It was empty. ‘Hey-ho,’ he said philosophically. ‘Sorry to disappoint you, old darling. Why don’t you keep the book, though. I’m sure you’ll get more out of it than I will.’

I started reading it on the Underground, rattling out eastward in an almost empty mid-afternoon carriage, the sun, once we had emerged from the tunnels, burning the back of my neck. The book was beautifully designed, refined but without pretension, with restfully little of the brilliant text on each thick, wide-margined page. It was a treasure, and I could not decide whether to keep it for myself or to give it to James. Imagining his pleasure at receiving it, and then feeling apprehensive about Arthur, I looked out of the window at the widening suburbs, the housing estates, the distant gasometers, the mysterious empty tracts of fenced-in waste land, grass and gravelly pools and bursts of purple foxgloves. Modern warehouses abutted on the line, and often the train ran on a high embankment at the level of bedroom windows or above shallow terrace gardens with wooden huts, a swing or a blown-up paddling pool. Everywhere the impression was of desertion, as if on this spacious summer day just touched, high up, with tiny flecks of motionless cloud, the people had made off.

It was a false impression, as I found when my stop came and, slipping the book into my jacket pocket and taking up my bag, I went out onto a busy platform and then into a crowded modern high street with mothers shopping, babies in push-chairs blocking the way, traffic lights, delivery vans, the alarming bleep of pedestrian crossings. It was like an anonymous, exemplary street, with a range of nameable activities, drawn to teach vocabulary in a foreign language.

I was amazed to think it was in the city where I lived, and consulted my A-Z surreptitiously so as not to set off with faked familiarity in the wrong direction. The culture shock was compounded as a single-decker bus approached showing the destination ‘Victoria and Albert Docks’. Victoria and Albert Docks! To the people here the V and A was not, as it was in the slippered west, a vast terracotta-encrusted edifice, whose echoing interiors held ancient tapestries, miniatures of people copulating, dusty baroque sculpture and sequences of dead and spotlit rooms taken wholesale from the houses of the past. How different my childhood Sunday afternoons would have been if, instead of showing me the Raphael Cartoons (which had killed Raphael for me ever since), my father had sent me to the docks, to talk with stevedores and have them tell me, with much pumping and flexing, the stories of their tattoos.

I soon saw where I was going, three squat towers which rose above the rooftops of the street: they were some distance away and the shops had turned to curtained terraces by the time I branched off. At the end of a short side-street a narrow ginnel with concrete bollards led into the surprisingly wide area in which the blocks of flats stood. I wondered why they had been forced up to twenty storeys or so when they could easily have spread across the empty ground which they now overshadowed, where the streets which they replaced must once have run. With surreal bookishness the three towers had been named Casterbridge, Sandbourne and Melchester.

To get to Sandbourne I wandered across the worn-out grass on a natural path eroded by feet and children’s bikes. In the odorous stillness of the day I thought of the tracks that threaded Egdon Heath, and of benign, elderly Sandbourne, with its chines and sheltered beach-huts. Away to the left a group of kids were skateboarding up the side of a concrete bunker. I somehow expected them to shout obscenities, and was glad I had come ordinarily dressed, in a sports shirt, an old linen jacket, jeans and daps.

The buildings, prefabricated units slotted and pinned together, showed a systematic disregard for comfort and relief, for anything the eye or heart might fix on as homely or decent. Rainwater and the overflow pipes of lavatories had dribbled chalky stains across the blank panels, and above the concrete rims of the windows weeds and grass grew from the slime. The only variation came from the net curtains, some plain, some gathered back, a few fringed and archly raised in the middle like the hoop of a skirt. Behind them lay hundreds of invisible dwellings, very small and stuffy, despite the open windows from which, here and there, the thump and throb of pop music could be heard. I found myself sweating with gratitude that I did not live under such a tyranny, dispossessed in my own home by the insistent beat of rock or reggae.

Casterbridge, which I came to first, was connected to Sandbourne by a serviceway with, on one side, a double row of garages with buckled up-and-over doors, and on the other a six-foot wall screening, in various compartments, a generator and a number of institutional dustbins on wheels, large enough to dump a body in. At the end of this alley a group of skinheads were playing around, kicking beercans against the wall and kneeing each other in spasmodic mock-fights. One of them, slobbish, with moronic sideburns, and braces hoisting his jeans up around a fat ass and a fat dick, was very good. I looked at him for only a second; a phrase from the Firbank I had just been reading came back to me: ‘Très gutter, ma’am.’

Perhaps it was he and his friends who had smashed the glass of one of the doors into Sandbourne: it was now blind with hardboard. The lift arrived as I went into the hall, and a very old man with a hat and all his buttons done up shuffled out, looking at me apprehensively. It was a big, functional lift, like a goods-lift, with a battered door that shuddered shut and metal walls sprayed thickly with graffiti, and with the menacing, urchin monogram of the National Front scratched over and over in the paint.

It was only when I got out at the ninth floor that I began to feel anxious. The door closed behind me at once and left me alone. I could hear a television from within one of the flats, and the sound of a police siren outside came from very far off, from some other transgression in the hot summer world below.

The flats opened off the corridor where I stood in electric light; transverse corridors, with windows at each end, formed an H plan, and I went along very cautiously till I found the right number. By the door there was a bell and under it a little plastic window showing a card with ‘HOPE’ written on it in blue ink. I nodded my head mirthlessly over this, my heart raced as I lifted my finger and held it in the air, wincing with trepidation, before stepping back and slipping quickly round the corner and looking out of the window. I saw the suburban sprawl, the tall windows of a Victorian school, gothic spires rising over housetops, and then immediately below the yellowing grass, the children skateboarding, surprisingly quiet.

I wanted to see Arthur, and make sure he was all right. I wanted to touch him, support him, see again how attractive he was and know he still thought the world of me. I stood very still, hearing the racing on television from inside the flat I was nearest to. I had hardly allowed myself to think what I would actually say, if his mother wanted to know who I was, or his drug-dealing brother; or if he had never returned home since the day of the fight, and had disappeared from their lives as completely as he now had from mine. Perhaps I should abandon the whole thing, the pains I was taking. Perhaps I could see him from a distance, coming across the grass below with friends, and know that he was all right, and slide away.

It is horrible to be cowed by circumstances. I crept back to the Hopes’ door, mechanically obedient to my original plan. The doorbell was shrill. I massaged my face into a plausible, friendly expression and stood back.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.