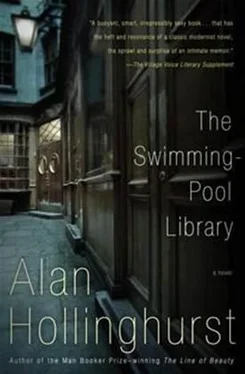

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I was inordinately, unaccountably moved by this-except that I knew it for what it was, a profound call of my nature, answered first at school by Webster, muffled, followed obscurely but inexorably since. Was it merely lust? Was it only baffled desire? I knew again, as I had known when a child myself, confronting a man for the first time, that paradox of admiration, of loss of self, of dedication… call it what you will. Back in the sunshine-fiercely hot now, so that I at once put on my topi, & walked out conscious of some inner effort of self-effacement, of humility wrestling with grandeur & compassion-the scamps, repelled from Simon Artz’s door by a fearsome old Arab with a peaked cap and a cane, flocked about me, some pushy & assertive but others festive and friendly, trying to take me by the hand. I had the absurd vision of myself as a doting schoolmaster leading off his charges on some special treat, & for the first time I had to assert myself, strike out airily with my hand to repel the little demons. Then I felt childlike myself, very pink & white, laughable in my indignation, & my authority much too big for me, as if bought in anticipation of my ‘growing into it’.

I have omitted to mention the smell, which as soon as the ship docked & the wind it made was stilled, rose to the nostrils from the land. ‘Ah, the East!’ Harrap had said connoisseurially. It is not a smell one could anticipate, or even much care for in itself, but I relished its authenticity at once-a dusty dryness, & a sweetness, a foetor, as it might be near some perpetual meat-market, a smell utterly unhygienic and inevitable.

The other streets here might have borne exploring, but I was thirsty & went to sit in the shade of the tea-terrace. The tea, served impractically in a glass, was refreshing, somehow muddy & more sustaining than tea I am used to. All the while there was Sinai, very hazily apparent in the distance, & near to the spectacle of the ship being refuelled, which is done by an endless chain of Egyptians, some in blue or white djellabas, others naked but for a knotted nappy around the loins, lean, by & large, & sinewy. All the while they pass on baskets of coal, their foreman leading them in monotonous chanting, a call raised, a general echoing response, the words, indistinguishable to my Oxford Arabic, intensifying the impression of changeless pharaonic labour. Meanwhile on the quay, & even for a while from the bows of the ship until an official stopped them, three or four youths, virtually naked & entrancingly wild & fearless, were diving for coins.

As I sat & watched them, my pleasure & fascination evident perhaps in my gaze, a handsome young man with the immemorial flat, broad features of the Egyptian, a blue djellaba & a circular embroidered hat that made him look like an exotic afterthought of Tiepolo, sidled among the tables towards me, half-concealing behind him a battered valise. I had been thoroughly trained to expect him & his inevitable offers of fake antiquities, but as I was still alone-the others not yet having arrived at the rendezvous- & in my mood of exultant curiosity & celebration, I let him approach. The major-domo, I noticed, kept an eye out for my reaction, & when I did not object, looked at the youth in a way which suggested some sinister understanding between them, as if, the protocol of deference having been observed, I was now a legitimate victim of their antique trade.

‘You see Lesseps statue, m’sieu,’ he said, standing over me solicitously.

‘No, no,’ I replied tolerantly.

‘Is very good, m’sieu. You like. You like, I take you. Only 50 piastres. Is most instructive.’

‘No thank you,’ I said firmly, but with an amused look, I suppose, which may have encouraged him-if encouragement were needed-to carry on. He hoisted his case up then on to the table, although I raised a hand to promise him it was no use.

‘Here is postcard picture of statue of Lesseps, m’sieu. Is most instructive & also relaxing. Also is only ten piastres.’ I bought one of these &, since we wd not go there, one of the Pharos & one of Pompey’s Pillar. Encouraged, he rummaged inside a cloth bag, & produced a small brown bottle, taking the opportunity too to pull a chair up beside me & sit down. He had a strong, not particularly pleasant smell. ‘Here is very special drink, m’sieu. Very good for you & for your lady.’ He looked at me keenly & I felt myself colour. ‘Is the cocktail of love, m’sieu. Is the wine of Cleopatra.’

‘No, no, no,’ I said, flustered. To my surprise he was sensitive to this & put the bottle away. He seemed prepared already to give me up, afraid to overstep the mark, & packed up his case again; some other Europeans approached an adjacent table, & I was glad to be seen successfully repulsing this mountebank, fascinating & confidential though he was. Leaning forwards as though to rise, & so hiding what he did from our neighbours, he produced, almost prestidigitated, from inside his robe, from somewhere mysterious about his person, a hand of postcards which he quickly fanned & as quickly swept together again & covered. It should not have surprised me that there was a market for such things here. He may only have been taking an inspired commercial guess in showing them to me. But I was keenly dismayed, humiliated, feeling that he had read me like a book & I, in the glimpse I caught of naked poses-all male, young boys, fantastically proportioned adults, sepia faces smiling, winking-had confusedly admitted as much. I declined him sternly, & with an amiable, philosophical bow he withdrew to pester the newly arrived party.

Tonight we travel south along the Canal. I have just walked on deck under stars; it was quite bracingly cold. Beyond the sheer canal walls there are occasional lights & fires: otherwise featurelessness & a distant horizon of hills to the east, and plain to the west, just perceptible as darker than the sky. Like a child I feel far too excited to sleep through my first night in Africa.

A couple of weeks later Charles rang me. As usual he was already talking when I raised the apparatus to my ear: ‘… my dear, and too appalled to hear that you’ve been vandalised.’

‘Charles! I’m much better now. I’ve got a false tooth very cleverly sort of welded on at the front…’

‘I’ve only just heard about it from our friend Bill.’

‘I didn’t know he knew.’

‘I was most dismayed. I went for a swim, you see. I hoped I might find you there. But I suppose…’

‘I haven’t been going in while I’ve been looking so hideous, but I hope to make an appearance in the next few days.’

‘Were you badly hurt?’

‘Well, I’ve got some cracked ribs, and there’s not much you can do about them, you just have to let them mend. The only permanent defect is a broken nose.’

‘Oh dear …’

‘It gives me a sort of pugilistic look-quite like one of Bill’s boys.’

‘Even so… Who’s been looking after you? Can I send you bouquets?’

‘I have a wonderful doctor, and a very sweet friend. I’m fine.’

There followed a typical Nantwich pause, which, heard over the telephone, was more disconcerting than when one was with him. I stood expectantly by. Suddenly he was on the air again. ‘Come over to Staines’s tomorrow, if you want to see something really extraordinary.’

‘I had a fairly extraordinary time there a few weeks ago.’

‘It may be a bit vulgar. About seven o’clock.’ There were a few seconds of reedy respiration, and then he hung up.

I remembered from something he had said before-about Otto Henderson’s cartoons being ‘vulgar’-that this was a word Charles used, as I had used it when a little boy, to mean indecent, in the manner of, say, a rude joke. Of course, anything remoter from the vulgus than the arty pornography of Henderson and Staines would have been hard to imagine; but it was telling that in his euphemism Charles made the connection, as though his taste for them somehow joined him with the crowd.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.