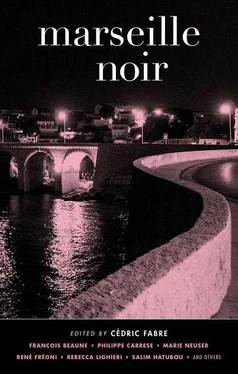

Cédric Fabre - Marseille Noir

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Cédric Fabre - Marseille Noir» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: akashic books, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Marseille Noir

- Автор:

- Издательство:akashic books

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Marseille Noir: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Marseille Noir»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Marseille Noir — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Marseille Noir», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Marseille Noir

This book is dedicated to the loving memory of our friend Salim Hatubou, who left us on March 31, 2015.

— The Authors

Introduction

Marseille Calling

In 1900, after fifty years of unprecedented growth and modernization that radically transformed the city, Marseille was the queen of the Mediterranean, tirelessly drawing its power from the vast French colonial empire. In the eyes of the writer and reporter Albert Londres, it had acquired the status of an “imaginary court in a universal palace of trade.” Its decline began in the 1960s, when France lost its colonies, and this accelerated with the oil crises of the following decade.

Marseille’s past glory is still visible through its industrial remains: old, abandoned oil refineries, soap and brick factories you come upon at a bend in the road between L’Estaque and Callelongue. Today, moving through the city from one end to the other can feel like a dive into a socioeconomic slump, with its decrepit villages and its housing projects in constant decay and an unemployment rate sometimes over 50 percent.

A postindustrial city might be defined by the distance that separates it from its golden age, because it’s at the heart of that space-time — when a page of glorious history has been turned — that the mythologies and fantasies, the resentments and nostalgias that play a part in shaking up and rebuilding its identity, are formed. For if its changes are sometimes blindingly obvious, its permanent features become more tangible. “Marseille, always bound for elsewhere,” wrote the French author and songwriter Pierre Mac Orlan. Unfortunately, the horizon seems — let’s say momentarily to remain optimistic — out of reach, and the city is still trying to figure out a future for itself. And indeed, it does keep transforming, sometimes for the best, if only in its outward appearance. It was named the 2013 European Capital of Culture, and our dream is that a stimulus like this will be the opportunity for a new chapter. A city of tragedy — it is partly Greek — Marseille does, however, have resources, and can count on its formidably dynamic youth.

Marseille is a “world city”—which makes one think of London more than Paris, in many ways — a crossroads for the people of Europe and the Mediterranean, a city that welcomes all migrants and exiles. It is a city that embodies the rabble-rousing, tough-guy side of the whole French nation. People like its cocky humor and its accent as much as they fear its spirit of rebellion. In fact, its identity is often reduced to a sports slogan, Proud to be Marseillais, which also reflects a feeling of abandonment and helplessness. Here socioeconomic struggle brings people together and unites them just as much as the wins of the Olympique de Marseille soccer team. It has the aura of noir, an aura that its residents often love as much as they hate, enlightened — or blinded — by that southern light. “You can’t understand Marseille if you’re indifferent to its light. It forces you to lower your eyes,” said Jean-Claude Izzo, the extraordinary novelist who finally gave Marseille back its voice after decades of almost no decent literary fiction.

Fooled by clichés that it was partly responsible for creating, Marseille sometimes portrays itself with an unconscious, disorganized strategy to constantly scramble its image. The city is never where you think it is. Local elected officials have often denounced “Marseille bashing” in their speeches, promising to improve its image before they make a commitment to fix its problems. While the cover headline of a Parisian weekly recently read, “Marseille, a Lost Territory for the Republic”—the vast majority of its people respect the laws of the Republic, vote, and pay their taxes, thank you very much — the New York Times declared it was the second must-visit destination, after Rio and before Nicaragua. Marseille is frequently reduced to the capital of delinquency and corruption in France. But for journalists looking for this raw reality, it is often difficult to grasp and define, since it is composed of a multiplicity of fictional fragments.

Marseille’s violence has become the violence of a closed city, wedged between the sea and the hills and thus often turned against itself. The killings linked to drug deals are blown out of proportion; and the reality of the ever-increasing economic gap, between the north and south and the violence it results in, is neglected. Of course there is organized crime. Michel Foucault said it’s on the margins that the center is constructed. And local organized crime has been connected to politics for a long time, going back to the German occupation of France during World War II when the Guérini brothers chose the side of Gaston Defferre, an important figure in French history who went on to become the longtime mayor of Marseille. And the image of Marseille as a city of thugs goes back even further: it was in the second half of the nineteenth century that the city acquired the reputation of being dangerous, when crime was becoming “organized” little by little, and it continued all the way to the famous “French connection” of the ’60s and ’70s.

Today the crime tends to be disorganized, fragmented, more violent: the kids mowed down by gunfire are often under twenty-five.

In such a context, how can culture be given the place it deserves? Before Marseille was labeled the European Capital of Culture, we were already patching together garage rock concerts, beach parties with deejays, art shows, theater and dance performances, all with a do-it-yourself spirit. Each one in his or her own corner, more or less; private resourcefulness that held little interest for politicians. People deplored Marseille’s constant reluctance to honor its own artists, musicians, and writers — an old tradition. You had to leave in order to succeed. The writer André Suarès, strolling through the neighborhoods of Sainte-Marthe, Saint-André, and Saint-Julien, said that we have always produced saints when poets were needed. Marseille writers are still not highly regarded, neither here nor elsewhere. They’re accused of “doing their Pagnol”—a reference to Marcel Pagnol’s folksy plays that have become classics — before they’re even read, and they remain largely unknown.

Yet how can one write about this city and its people any other way than through fiction? Reality here seems so completely unbelievable. If elsewhere the crime novel can claim a kind of “socio-realism,” in the tradition of Zola or Vallès, here the genre can rapidly turn into social surrealism. Because here, a gang of youths can “rob” a downtown parking garage and manage it for months under the nose of the police, collecting money and raising the gates manually, before anyone finally intervenes; because here, too, when we try to honor a poet like Rimbaud (who died in Marseille) and we can’t find an available stretch of an avenue or alley to bear his name, we settle the matter by baptizing a space in the Saint-Charles train station the Arthur Rimbaud Waiting Room — inaugurated by none other than Patti Smith.

For all these and many more reasons, Marseille provides magnificent material for writing. For a long time, when it still had its eye on the sea, it was in fact a veritable “open city” for writers on shore leave.

“Marseille belongs to whoever comes from the open sea,” observed the poet and novelist Blaise Cendrars. Stendhal, Zola, and Mérimée wrote of its excess, its fiery personality, and its cosmopolitanism. It welcomed some of the greatest globe-trotting writers: Joseph Conrad, Albert Londres, Pierre Mac Orlan, Blaise Cendrars, Walter Benjamin, Mary Jayne Gold, Claude McKay, Anna Seghers, Ousmane Sembene. all lost travel writers and novelists, advocates of a vagabond literature that turned Marseille into one of the capitals of “world fiction” well before the English defined the concept. The literary journal Les Cahiers du Sud, which was founded by Jean Ballard in 1925 and lasted into the mid-’60s, was a brilliant illustration of this. At the same time, poets and lovers of literature were growing up in the city, from Victor Gélu to Louis Brauquier, as well as André Suarès, all largely forgotten today. It’s not surprising that it became a capital of rap and slam poetry, for Marseille knows, intimately, what “popular culture” means.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Marseille Noir»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Marseille Noir» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Marseille Noir» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.