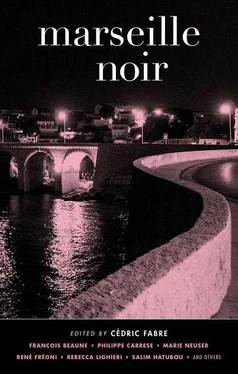

Cédric Fabre - Marseille Noir

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Cédric Fabre - Marseille Noir» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: akashic books, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Marseille Noir

- Автор:

- Издательство:akashic books

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Marseille Noir: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Marseille Noir»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Marseille Noir — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Marseille Noir», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Twenty years went by. Marseille changed somewhat, on the surface: the renovation of La Joliette to attract rich tourists, the promotion of our historical heritage, the destruction of the horrible high-rise parking garages and bypasses that used to disfigure the downtown area, even the architecture of the new museum near the cathedral — all that’s very good, quite a success, I must admit — but it’s only on the outside; it’s a trompe l’oeil. Inside, nothing’s changed, or almost nothing. In any case, the ordinary people of Endoume are still the same.

On the other hand, what used to be called “the mob” is practically gone: modern, cynical free-market society got the better of it — and in this respect, yes, from my point of view, yes, it was better in the old days. Today, there are just a few bosses scattered here and there throughout the city and the suburbs, and they’re more and more vicious. But when all is said and done, maybe they haven’t changed that much. The rules and methods are just more violent and arbitrary, that’s all — although, relatively speaking, no more so than those of society as a whole. In fact, one might wonder what miracle could have prevented that generalized violence in human relationships, that extreme tension in the workplace, even in the streets, from spreading to all sectors of society, including what used to be called “the mob.” Like employees and executives, gangsters had to show “flexibility”: most of them turned into more or less respectable businessmen. New markets popped up. New rackets. New networks. You had to adapt. Ange was able to do it. He moved upward, and got much richer. But the “worker bees,” the invisible people, guys like me, they don’t see too much difference. The Milous and Doumés, for example, are still just as dumb, servile, and violent. Francis Girard, a.k.a. Le Blond, a.k.a. Hay-Head, and now called The Old Guy, was let out in 2005 for medical reasons, then arrested again in 2009 for dealing drugs. Today he’s still locked up in Baumettes prison.

And for the rest, life goes on in town just as it did before. Like before, city hall tries to shove the poor out of the center of the city and it still doesn’t work. Like before, though not much more than before, the gangs are killing each other off slowly but surely and that has no more effect on the daily life of the people of Marseille than it did before, even if the media makes a big fuss about it. As ever, it’s too hot, as ever the wind blows too hard, as ever everybody speaks too loud and gets mad too fast but it doesn’t last, it smells just as bad in the summer, the streets are just as dirty, and on the whole, it doesn’t make a very good impression. It’s always been like that. All the clichés keep getting trotted out: Marseille is the city of excess, and that’s supposed to be what makes it as irritating as it is endearing.

In Endoume, it seems nothing has really changed, aside from the franchise signs that replaced the little shop signs of my childhood, and the disappearance of Fornasero’s plumbing business right next to my place, and Bijaoui’s grocery store. I work with René Fabrizio: I sell cars for the Renault dealer in La Capelette. Nothing exciting, but still, it’s better than harassing bar owners to pay back their bets, and risk finding myself on a stretcher with two pieces of lead in my belly like my dad.

No, actually, something did change: for the last twenty years, Josiane’s been living with me.

She was happy to come back to the little street of her childhood. When we got there together, she clapped her hands and cried out in joy, like a little girl. She even flew into my arms, but even this didn’t cheer me up. I felt cornered, humiliated, reduced to nothing. I never would have thought I could live with someone I hadn’t chosen, especially someone who is relatively nuts. And yet I have. True, I didn’t really have a choice. I wouldn’t say we form a couple, but we live together without any clashes. When Ange wants to visit his sister, he calls me and we agree on a time when I can leave the house, because he doesn’t want to see us together.

Josiane’s really more than “borderline,” but Ange was right: she’s gentle, sensitive, and very emotional. Incapable of caring for herself. Unfit for life in everyday society. Still beautiful, despite her age. Supple as a liana, slim, elegant. Easygoing. Silent, available, and discreet. Often miles away, her eyes lost gazing at the ceiling for hours on end, or contemplating an invisible spot while talking incomprehensibly in a small, plaintive voice. She never asks anything of me, except to be home from time to time. I do in fact like her. Her presence is soothing. And now, after twenty years, I’ve grown attached to her. Through René Fabrizio, I found a kind of nurse who keeps her company when I’m not there, during the day when I’m working or in the evening when I feel like going out to see friends or flings. Sometimes she has a fit and starts crying and twisting her hair — graying now, but still prettily curled — between her long, slender fingers. Then she mumbles and walks over to me, gracefully swaying her hips.

I never saw Ange Malatesta again.

EXTREME UNCTION

by FRANÇOIS THOMAZEAU

Vélodrome Stadium

It happened four times. André would come get me at Grandma’s on Wednesday mornings and take me to Vélodrome Stadium. On the way, in his big, brand-new German sedan, we wouldn’t exchange a word. He’d light up a cigarette, lower his window, stick out his arm, and cough all the way. At the stadium, a flunkey would open the gate for him and we’d park smack in the middle of the empty parking lot in front of the main entrance that said Jean Bouin. When there was someone there besides the guard, he’d politely say hello to André, lowering his eyes. Occasionally some bolder guys would throw out a, “Hi, Dédé.” And he’d cough to answer them.

Then he’d pull me into an empty part of the stands, never the same one. We’d set our butts down on the blue seats, strangled by our scarves, with the tramontane wind howling at us. Way up in the stadium, above the railing where the crowd looks like it’s going to spill overboard on the nights when there’s a game, the seagulls would protest our presence. There were only the two of us, except for the raw-boned silhouette of an old guy in denim overalls leisurely pushing his lawnmower along the bands of light green grass. Once we’d sat, we’d stay there for a long time without saying anything, long enough for André to finish his Marlboro. Then he’d turn to me, look me in the eye, and start talking. He said anything that came into his mind: he liked Andalusian resorts in the fall, nightclubs at dawn—“when it’s time to stuff your cash in your pocket before you go home to bed,” nameless roadside hotels, empty stadiums frozen in silence. Hideouts.

“That’s what my life is like, see.”

I didn’t see anything, but André seemed happy to be there. Grandma had told me to be good. And try to be nice. So I acted as if I was happy too. He’d pass me potato chips in crumpled packs in the colors of our soccer team, the Olympique de Marseille. And I’d suck in the sickening foam of my cans of Coke.

“You want me to tell you a story?”

And every time, we were in for a good quarter of an hour. You’d think André was telling me a story before tucking me in.

The first time was in November and the cold was pinching my cheeks the way old ladies do to chubby babies. Dédé told me the story of a boxer. The way he was talking about him, with his fists squeezed against his chest, I had the feeling he’d known him. He was staring straight at some vague spot in the stands across the field.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Marseille Noir»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Marseille Noir» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Marseille Noir» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.