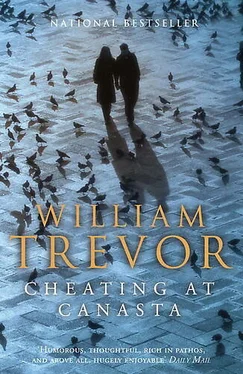

William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cheating at Canasta

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cheating at Canasta: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cheating at Canasta»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Cheating at Canasta — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cheating at Canasta», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘If you would like me to.’

Connie nodded. And they could talk about it, she said. If he read it they could talk about it.

‘Yes, we could. You’ve always liked Teresa, Connie. You’ve always liked Melissa and Nat. It isn’t easy for us to understand.’

‘Couldn’t it stay here, the furniture you don’t want? Couldn’t we keep it here?’

‘Out here it’s a bit damp for furniture.’

‘Couldn’t we put it back then?’

‘Is that what’s worrying you, Connie? The furniture?’

‘When the books are thrown away I’ll know what every single one of them was about.’

‘But, for heaven’s sake, the books won’t be thrown away!’

‘I think they will be, really.’

Robert went away. He didn’t look for Teresa to tell her about the conversation. Every year at this time he erected a corral where his ewes paddled through a trough of disinfectant. They crowded it now, while he remembered his half-hearted protestations and Connie’s unsatisfactory responses. ‘Oh, come on, come on! Get on with it!’ Impatient with his sheep, as he had not been with his daughter, he wondered if Connie hated him. He had felt she did, although nothing like it had showed, or had echoed in her voice.

From the roof she saw a car she’d never seen before, and guessed why it had come. In one of the drawers of the rickety Welsh dresser she’d found a shopping list and thought she remembered its being lost. Ironing starch . Baking powder , she’d read.

The car that had come was parked in the yard when she came down from the roof. A man was standing beside it. He referred to the furniture that was to be sold, as Connie had thought he might.

‘Anyone around?’ he asked her.

He was a bigred-faced man in shirtsleeves. He’d thought he’d never find the house, he said. He asked her if he was expected, if this was the right place, and she wanted to say it wasn’t, but Teresa came out of the house then.

‘Go and get your father,’ she said, and Connie nodded and went to where she’d seen him from the roof.

‘Don’t sell the furniture,’ she begged instead of saying the man had come.

One night, when the wedding was five days away, Teresa drove over to the farm. About to go to bed, she knew she wouldn’t be able to sleep and wrote a note for Melissa, saying where she was going. It was after half past one and if there hadn’t been a sign of life at the farm she would have driven away again. But the lights were on in the big drawing-room and Robert heard the car. He’d been drinking, he confessed as he let Teresa in.

‘I don’t know how to make sense to her,’ he said when they’d embraced. Without asking, he poured her some whiskey. ‘I don’t know what to do, Teresa.’

‘I know you don’t.’

‘When she came to stand beside me while I was milking this afternoon, when she didn’t say anything but I could hear her pleading, I thought she was possessed. But later on we talked as if none of all this was happening. She laid the table. We ate the trout I’d fried. We washed the plates up. Dear Teresa, I can’t destroy the childhood that is left to her.’

‘I think you’re perhaps a little drunk.’

‘Yes.’

He did not insist that there must be a way; and knowing what frightened him, Teresa knew there wasn’t. She was frightened herself while she was with him now, while wordlessly they shared the horrors of his alarm. Was some act, too terrible for a child, waiting in the desolation of despair to become a child’s? They did not speak of what imagination made of it, how it might be, nurtured in anger’s pain, in desperation and betrayal, the ways it might become unbearable.

They walked on the avenue, close to one another in the refreshing air. The sky was lightening, dawn an hour away. The shadows of danger went with them, too treacherous to make chances with.

‘Our love still matters,’ Teresa whispered. ‘It always will.’

A calf had been born and safely delivered. It had exhausted him: Connie could tell her father was tired. And rain that had begun a week ago had hardly ceased, washing his winter seeding into a mire.

‘Oh, it’ll be all right,’ he said.

He knew what she was thinking, and he watched her being careful with the plates that were warming in the oven, careful with the coffee she made, letting it sit a moment. Coffee at suppertime was what he’d always liked. She heated milk and poured it from the saucepan.

The bread was sawn, slices waiting on the board, butter beside them. There were tomatoes, the first of the Blenheims, the last of the tayberries. Pork steak browned on the pan.

It was not all bleakness: Robert was aware of that. In moments like the moments that were passing now, and often too at other times, he discerned in what had been his daughter’s obduracy a spirit, still there, that was not malicious. In the kitchen that was so familiar to both of them, and outside in the raw cold of autumn when she came to him in the fields, she was as events had made her, the recipient of a duty she could not repudiate. It had seemed to her that an artificial household would demand that she should, and perhaps it might have.

Robert had come to understand that; Teresa confessed that nothing was as tidy as she’d imagined. There were no rights that cancelled other rights, less comfort than she’d thought for the rejected and the widowed, no fairness either. They had been hasty, she dared to say, although two years might seem a long enough delay. They had been clumsy and had not known it. They had been careless, yet were not careless people. They were a little to blame, but only that.

And Robert knew that time in passing would settle how the summer had been left. Time would gather up the ends, and see to it that his daughter’s honouring of a memory was love that mattered also, and even mattered more.

Old Flame

Grace died .

As Zoë replaces the lid of the electric kettle—having steamed the envelope open—her eye is caught by that stark statement. As she unfolds the plain white writing-paper, another random remark registers before she begins to read from the beginning. We never quarrelled not once that I remember .

The spidery scrawl, that economy with punctuation, were once drooled over by her husband, and to this day are not received in any ordinary manner, as a newspaper bill is, or a rates demand. Because of the sexual passion there has been, the scrawl connects with Charles’s own neat script, two parts of a conjunction in which letters have played an emotional part. Being given to promptness in such matters, Charles will at once compose a reply, considerate of an old flame’s due. Zoë feared this correspondence once, and hated it. As ever my love, Audrey : in all the years of the relationship the final words have been the same.

As always, she’ll have to reseal the envelope because the adhesive on the flap has lost its efficacy. Much easier all that is nowadays, with convenient sticks of Pritt or Uhu. Once, at the height of the affair, she’d got glue all over the letter itself.

Zoë, now seventy-four, is a small, slender woman, only a little bent. Her straight hair, once jet-black, is almost white. What she herself thinks of as a letterbox mouth caused her, earlier in her life, to be designated attractive rather than beautiful. ‘Wild’ she was called as a girl, and ‘unpredictable’, both terms relating to her temperament. No one has ever called her pretty, and no one would call her wild or unpredictable now.

Because it’s early in the day she is still in her dressing-gown, a pattern of tulips in black-and-scarlet silk. It hugs her slight body, crossed over on itself in front, tied with a matching sash. When her husband appears he’ll still be in his dressing-gown also, comfortably woollen, teddy-bear brown stitched with braid. Dearest, dearest Charles , the letter begins. Zoë reads all of it again.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cheating at Canasta» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.