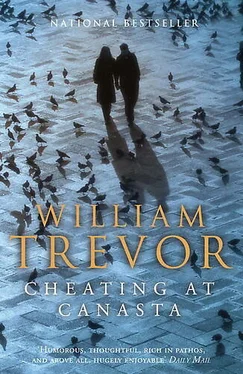

William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Trevor - Cheating at Canasta» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cheating at Canasta

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cheating at Canasta: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cheating at Canasta»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Cheating at Canasta — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cheating at Canasta», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Oh yes, the Alp Horn’s still there,’ Zoë hears a little later that morning, having eased open a door he has carefully closed. ‘Twelve forty-five, should we say? If your train’s a little late, anything like that, please don’t worry. I’ll simply wait, my dear.’

He’d been saying something she hadn’t managed to hear before that, his voice unnaturally low, a hand cupped round the mouthpiece. Then there’d been the hint of a reprimand because the old flame hadn’t written sooner. Had he known he’d have gone to the funeral.

‘I’m sorry to have hurt you so,’ he said later that Sunday, but words by then made no sense whatsoever. Five years of a mistake, she thought, two children mistakenly born. Her tears dripped on to her clothes while he stood there crestfallen, his good looks distorted by distress. She did not blow her nose; she wanted to look as she felt. ‘You would like me dead,’ she sobbed, willing him to raise his fist in fury at her, to crash it down on her, obliterating in mercy all that remained of her. But he only stood there, seeming suddenly ill-fed. Had she not cooked properly for him? her thoughts half crazily ran on. Had she not given him what was nourishing? ‘I thought we were happy,’ she whispered. ‘I thought we didn’t need to question anything.’

‘Nice to see the old Alp Horn again,’ his murmur comes from the hall, and Zoë can tell that he’s endeavouring to be cheerful. ‘Tell you what, I’ll bring a packet of Three Castles.’

There is the click of the receiver, the brief sounding of the bell. He says something to himself, something like ‘Poor thing!’ Zoë softly closes the door. Grace and Audrey had probably been friends for fifty years, might even have been schoolfriends. Was Audrey the one whom other girls had pashes on? Was Grace a little bullied? Zoë imagines her hunched sulkily into a desk, and Audrey standing up for her. In letters and telephone conversations there have been references to friends, to holidays in Normandy and Brittany, to bridge, to Grace’s colonic irrigation, to Audrey’s wisdom teeth removed in hospital. Zoë knows—she doesn’t often call it guessing—that after Audrey’s return from every visit to the Alp Horn Grace was greedy for the morsels passed on to her. Not by the blink of an eye could Grace reveal her secret; the only expression of her passion was her constancy in urging another letter. We think of you with her in that coldness . ‘Quite frail he looked,’ Audrey no doubt reported in recent years.

He did not stay with Zoë in 1967 because of love. He stayed because—quite suddenly, and unexpectedly—the emotions all around him seemed to have become too much: it was weariness that caused him to back off. Had he sensed, Zoë wondered years later, the shadow of Grace without entirely knowing that that was what it was? He stayed, he said, because Zoë and the two children who had then been born meant more than he had estimated. Beneath this statement there was the implication that for the sake of his own happiness it wasn’t fair to impose hardship on the innocent. That, though unspoken, had a bitter ring for Zoë. ‘Oh, go away!’ she cried. ‘Go to that unpleasant woman.’ But she did not insist; she did not say there was nothing left, that the damage had been done for ever. To the woman, he quoted his economic circumstances as the reason for thinking again. Supporting two households—which in those days was what the prospect looked like—was more than daunting. Grace says you wouldn’t have to leave them penniless. What she and I earn could easily make up for that. Grace would love to help us out . Had he gone, Grace would somehow have been there too.

Zoë knows when the day arrives. Glancing across their breakfast coffee at her, his eyes have a dull sparkle that’s caused by an attempt to rekindle an obsolete excitement: he was always one to make an effort. In a letter once Audrey referred to his ‘loose-limbed charm’, stating that she doubted she could live without it and be herself. He still has that lanky look, which perhaps was what she meant; what remains of his floppy fair hair, mainly at the back and sides of his head, is ash-coloured now; his hands—which Zoë can well imagine either Grace or Audrey designating his most elegant feature—have a shrivelled look, the bones more pronounced than once they were, splotches of freckles on skin like old paper. His face is beakier than it was, the teeth for the most part false, his eyes given to watering when a room is warm. Two spots of pink come and go high up on his narrow cheeks, where the structure of the cheekbones tautens the skin. Otherwise, his face is pale.

‘I have to go in today,’ he casually announces.

‘Not here for lunch?’

‘I’ll pick up a sandwich somewhere.’

She would like to be able to suggest he’d be wiser to go to a more expensive restaurant than the Alp Horn. Cheap food and house wine are a deadly combination at his time of life. A dreadful nuisance it is when his stomach goes wrong.

‘Bit of shopping to do,’ he says.

Once there was old so-and-so to meet but that doesn’t work any more because, with age, such figures can’t be counted upon not to give the game away. There was ‘the man at Lloyd’s’ to see, or Hanson and Phillips, who were arranging an annuity. All that has been tapped too often: what’s left is the feebleness of shopping. Before his retirement there was no need to mention anything at all.

‘Shopping,’ she says without an interrogative note. ‘Shopping.’

‘One or two things.’

Three Castles cigarettes are difficult to find. Audrey will smoke nothing else and it’s half a joke that he goes in search of them, a fragment of affection in the kaleidoscope of the love affair. Another such fragment is their shared delight in sweetbreads, a food Zoë finds repellent. They share unpunctuality also. Grace can’t understand how we ever manage to meet!

‘Should keep fine,’ he predicts.

‘Take your umbrella all the same.’

‘Yes, I’ll take my umbrella.’

He asks about a particular shirt, his blue striped one. He wonders if it has been ironed. She tells him where it is. Their three children—the boys, and Cecilia, born later, all married now—know nothing about Audrey. Sometimes it seems odd to Zoë that this should be so, that a person who has featured so profoundly in their father’s life should be unknown to them. If that person had had her way Cecilia would not have been born at all.

‘Anything you need?’ he offers. ‘Anything I can get you?’

She shakes her head. She wishes she could say: ‘I open her letters. I listen when there’s a phone conversation.’ She wishes he could tell her that Grace has died, that his friend is now alone.

‘Back about four, I expect?’

‘Something like that.’

Had he gone off, she wouldn’t still be in this house. She wouldn’t be sitting in this kitchen in her black-and-scarlet dressing-gown, eyeing him in his woolly brown one. She’d be living with one of the children or in a flat somewhere. Years ago the house would have been sold; she’d not have grown old with a companion. It was most unlikely there would ever have been another man; she doubted she’d have wanted one.

‘I dreamed we were on a ferry going to Denmark,’ he unexpectedly says. ‘There was a woman you got talking to, all in black.’

‘Prettily in black?’

‘Oh, yes. A pretty woman too. She used an odd expression. She said she was determined to have what she called a “corking child”.’

‘Ah.’

‘You sat me down in front of her and made me comment on her dress. You made me make suggestions.’

‘And did you, Charles?’

‘I did. I suggested shades of green. Deep greens; not olive like my trousers. And rounded collar-ends on her shirt, not pointed like mine. I made her look at mine. She was a nice woman except that she said something a little rude about my shoes.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cheating at Canasta» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cheating at Canasta» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.